Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Deborah MathisApril 04, 2018

They took different approaches, but two new television documentaries about Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. illustrate and underscore the difficulties in staying true to a movement’s guiding light.

“King in the Wilderness” (HBO) takes us through the last three years of Dr. King’s life. By 1965, King was tired, having spent the better part of the last 10 years on the “battlefield” in marches, speeches, meetings, pickets, sit-ins and jail—time away from his wife and young children and parents. In one poignant segment, we learn that he yearned for more restful time with his family and even promised his mother that he would make such occasions happen more often.

Marks, Mississippi, 1968 (the Rev. Dr. James Lawson seen on far left). Source: Poor People's Campaign.

A year before he was assassinated, Dr. King delved into the highly charged debate over the Vietnam War, taking a firm and unequivocal stance in opposition. Many supporters, including some of his closest advisors, had practically begged him not to speak out against the war and risk alienating President Lyndon Johnson, who had ushered the Civil Rights and Voting Rights Acts through a fitful Congress. The press weighed in too.

“Many who listened to him with respect will never again accord him the same confidence,” moaned the Washington Post. Indeed, many of his former friends and supporters abandoned him, a loss that long-time aide and family friend Xernona Clayton says Dr. King found heart-breaking.

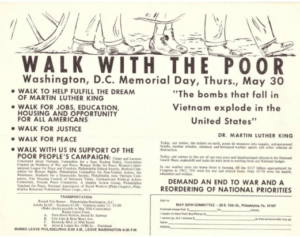

"'The bombs that fall in Vietnam explode in the United States', -Dr. Martin Luther King..." Source: Poor People's Campaign.

To add to his woes, King was increasingly hounded by a younger, militant faction of the civil rights movement that sometimes ridiculed his nonviolent model and threatened to usurp it. “King in the Wilderness” is a study in the temptations to capitulate to fatigue, political expediency and bandwagon, and the importance of maintaining the integrity of a movement.

“Hope and Fury: MLK, the Movement and the Media” (NBC) explores Dr. King’s deft handling of the news media and his recognition of its insatiable appetite for stories involving conflict. He understood the power of imagery—ordinary men and women peacefully advancing against a phalanx of armed, club-wielding agents of the state and defenders of the status quo—and figured, rightly, that the media would pounce on the contrast. The film notes his miscalculation in 1961, when Albany (Georgia) Police Chief Laurie Pritchett outwitted King’s anti-segregation demonstrators by abstaining from physically injuring the protesters. Consequently, television cameras captured scene after scene of peaceful men and women being arrested by officers behaving more like ushers and escorts than oppressors. Even the strategy of overwhelming the city jails was foiled; Pritchett had arranged to jail arrestees in several different facilities across south Georgia.

Martin Luther King, Jr.’s friend, Mahalia Jackson (seen here in 1964), sang at his funeral. Source: Wikipedia/Hugo van Gelderen (ANEFO) - GaHetNa (Nationaal Archief NL), CC BY 4.0.

Without the imagery of conflict to feed on, media attentions waned. It appeared the movement had devolved into a gathering of disgruntled but peaceful protesters being duly but peacefully arrested. The once-stark line between good and bad now faded, the impact softened and the moral outrage it engendered cooled.

Wisely, King regrouped and returned to the tried and true. A Children’s Crusade in Birmingham would be controversial and dangerous, but King knew Police Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor would not demur, not even if it offered a moral advantage. Indeed, the calamity of snarling dogs, bone-crushing night sticks and powerful fire hoses being turned against hundreds of peaceful youngsters horrified readers, listeners and viewers nationwide and around the world. On cue, the media perked up, its coverage once again trained on the contrast between peaceful protesters and violent authority.

What both documentaries affirm is that, whatever the conundrum, temptation or setback, Dr. King took care to protect the integrity of the movement, even if it entailed risk and cost. Had he caved into self-pity and retired early; or taken the politically expedient route and stayed out of the war debate; or forsaken the strategy of disruption and conflict; or yielded to the bandwagon by accepting violence as a righteous alternative, his movement may well have gone the way of so many others—an episode of history that sparks more talk than reflection. A piece of the past that has little bearing on the future. An idea whose time came and went, rather than an abiding truth that we celebrate today.

Deborah Mathis

Deborah Mathis is a senior journalist. Previously as ICNC’s Director of Communications, Deborah developed, executed and coordinated ICNC’s communications, marketing, and media relations, working in collaboration with the organization’s staff and advisors. She helped develop the Minds of the Movement blog and served as co-editor.

Read More