Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Amber French and Olga SagaidakJune 29, 2022

Cet article est aussi disponible en français ici.

Ця стаття доступна українською мовою.

I met Olga Sagaidak last May at the Ukrainian Cultural Center in Paris, France. In the large drawing room where I conducted our interview, the walls were lined floor-to-ceiling with jaw-dropping photography of war destruction and street art protesting Putin’s 2022 invasion of Ukraine. My stomach knotted when, leaning forward for a closer glimpse of one anti-war drawing, I realized it had in fact been sketched by the hand of a Ukrainian child.

Beholding this panorama—overwhelming both visually and emotionally—I learned about bold ways the Ukrainian art world is nonviolently resisting occupation. In this post, I channel Olga Sagaidak’s knowledge of unarmed civilian protection at cultural sites in Ukraine. I also analyze the Ukrainian art world's call for an international boycott of Russian culture. In my second post, I discuss cultural documentary resistance: systematic recording of occupiers' destruction of the occupied country's culture, as a way to expose the truth and possibly obtain reparations once the war is over.

A cultural activist’s perspective

The Ukrainian Cultural Center in Paris, May 2022. Credit: Amber French.

Olga Sagaidak is from Kyiv where she served on the Supervisors’ Board at the Ukrainian Institute, a cultural diplomacy organization founded by the Cabinet of Ministers in 2017. When the Russian army invaded Ukraine on February 24, 2022, the Institute's work exploded with new dimensions, new challenges and dire political stakes.

My interviewee's experience in the art world ranges from having studied art history and co-owning an auction house to co-founding a charitable foundation that develops networks to connect the east, south, and “very west” of Ukraine through art and culture. Above all, she identifies as a cultural activist.

Click to enlarge. Ukrainian Cultural Center photo exhibit, May 2022. Credit: Amber French.

Early March, the day after Olga fled Kyiv to settle in Paris with her family, she came to the Centre culturel d'Ukraine en France (France's Ukrainian Cultural Center) to propose volunteer work alongside a few of her colleagues. The group resolved to amplify Ukrainians’ voices through art and build a cultural bridge with the French public. They want to urge the French to oppose Russian imperialism.

Olga is thus well-placed to understand the central role that culture plays in the war in Ukraine. More important, she understands how cultural resistance is key to preserving Ukrainian society and weakening Putin’s support. She efficiently summed up for me that “This war is a war of cultures.”

Unarmed civilian protection of cultural sites in Ukraine

One way Ukrainians are resisting occupation is through unarmed civilian protection of cultural sites. The actions usually involve museum staff and community volunteers evacuating art collections (including amid bombing), and/or staying on-site with the collections to resist Russian invasion and prevent pillaging. Olga reported that nearly all museum directors she knew of had been staying on-site with their collections.

The actions are usually spontaneous initiatives of ordinary people, as opposed to some NGO initiative. My interviewee clarifies that museum staff do not send out calls for volunteers. Most do not even talk about their actions after the works are evacuated, for security reasons obviously.

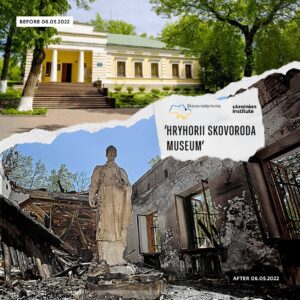

Click to enlarge. The Ukrainian Institute's "Postcards from Ukraine" project. This museum, an historical monument, was built in 1972 and destroyed by Russian artillery on May 7, 2022. Its collection, however, is in a safe place. Credit: Ukrainian Institute website.

As a result, not much information is being shared publicly about unarmed civilian protection of cultural sites. After all, Ukrainian cities are still at risk of occupation. Olga did, however, feel at liberty to share with me details regarding two museum collections that have escaped destruction and pillaging thanks to unarmed civilian protection.

At the Kharkiv Literary Museum, located close to the Russian border, staff began to pack up and relocate the collection even before the invasion on February 24. The museum director, Tetiana Pylypchuk, remained for some time at the museum following the invasion. Refusing for their work to be interrupted by occupation, museum staff are still organizing cultural activities [link in Ukrainian] in shelters or at Metro stations.

Not far from Kharkiv, the Hryhoriy Skovoroda National Literary Memorial Museum was destroyed on May 7. However, the collection had been removed to another site before the bombs fell, thanks to staff and community volunteers.

Now many Ukrainian museums are under occupation in Mariupol, Kherson, Berdiansk, Donetsk, and Luhansk. Sadly, despite widespread protection efforts, Russian soldiers have still reportedly managed to loot and export more than 2,000 of the most valuable works to Russia. (More in my second post on how the art world is addressing this problem through nonviolent resistance.)

Boycotting Russian cultural products and artists close to Putin

Russian president Vladimir Putin confers the title of Hero of Labor on conductor and artistic director Valery Gergiev, director of the Mariinsky Theatre, in May 2013. Credit: Kremlin.ru via Wikipedia.

Beyond local nonviolent resistance to preserve culture, Ukraine’s art world is also calling for an international boycott of Russian cultural products and artists close to Putin. Why? Olga expresses it best:

“It’s a way to support Ukraine. There are of course many important Russian historical figures, but right now if we block this cultural influence, we block the transmission of dangerous imperialist ideas to future generations. A lot of young Russian men don’t even know where they’re being sent off to, or why. Their mothers lose their sons and don’t get to see the bodies to know for sure what their fate was. So, it’s about culture, how we care about people in our country, how we care about our families. Killing, stealing, pillaging, it’s all about culture and education.”

At the request of the Ukrainian Institute, the title of Cannes Film Festival's opening film, "Z comme Z" (which contained a pro-war symbol) was changed to "Coupez". Credit: Allocine.

It isn’t easy to call for a boycott of Russian culture in a country like France, where Russian music, art, ballet and theatre are hugely popular. But, as Olga points out, it’s important to block Russian culture and push people to take a stand against the war—just in the current climate. And they are not calling to destroy Russian culture, like the Russians are doing to Ukrainian culture. They are just asking people to stop and think about what it means to consume Russian culture amid Putin's war.

The boycott has gained some international momentum so far. In March, the Vilnius International Film Festival (Lithuania) cancelled all Russian film screenings and instead promoted films by Ukrainian directors. Many Russian cultural figures known to be close to Putin have lost engagements in various parts of the world. One such individual is Valery Gergiev, who was recently fired from the Munich Philharmonic Orchestra (Germany) as its chief conductor.

The only viable option for preserving culture

Culture and sovereignty policies during wartime date back to World War II. These outdated policies, promulgated by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) do not allow for any sort of international intervention to protect cultural sites. Plus, especially at the outbreak of war, it’s just not feasible for a foreign museum to host threatened collections. The administrative and logistical aspects of such an undertaking would be a nightmare.

Thus, in parallel to the nonviolent resistance that Ukraine’s art world is waging, Olga and her colleagues are currently lobbying for new policies to protect cultural heritage during wartime. They have regular meetings at the UNESCO headquarters in Paris to pressure for action on the matter. Unfortunately, the discussions are only between professionals, not leadership—for now. Olga says that it will be very long process, as international organizations are very slow-moving.

_

In my follow-up post, I zoom in on cultural documentary resistance, which I define as oppressed people compiling evidence of culture that their occupiers have destroyed or pillaged—to establish the truth about these wartime crimes and to have a chance of obtaining justice.

Amber French

Amber French is Senior Editorial Advisor at ICNC, Managing Editor of the Minds of the Movement blog (est. June 2017) and Project Co-Lead of REACT (Research-in-Action) focusing on the power of activist writing. Currently based in Paris, France, she continues to develop thought leadership on civil resistance in French.

Read More

Olga Sagaidak

Olga Sagaidak is a Ukrainian cultural activist, art manager, and curator. Since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, she has been representing the Ukrainian Institute in France. As a cultural activist, she initiated and now curates for the Ukrainian Spring project (Printemps ukrainien) at the Ukrainian Cultural Center in Paris. Previously, Olga co-founded the charitable foundation The Depths of Art (Dofa Fund).

Read More