Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Amos OluwatoyeSeptember 01, 2022

On May 12, 2022, some students of Shehu Shagari College of Education in Sokoto State, Nigeria, killed a Christian teenager, Deborah Samuel, for alleged blasphemy of Prophet Mohammed. Deborah had complained through a voice note in her class WhatsApp group about how some of her colleagues were posting about religious issues in the group, which she regarded as nonsense, because the initial agreement was that the group should be used for academic updates.

A fellow student responded that Deborah had blasphemed Prophet Mohammed. A group of Muslim students reacted to the voice note and went looking for her with the intent to kill her. She was eventually found and dragged out from safety, beaten, stoned, and lynched to death.

The killing triggered a conflict among regional majority Muslims and the Christian minority when the video of the killing went viral on social media platforms. The video showed one of the main perpetrators boasting, “I killed her. I burnt her. You can see the matchbox I used in setting her ablaze.” The content trended online and triggered outrage that thankfully was channeled into nonviolent resistance among Christians and a few Muslims to denounce the extrajudicial killing and demand justice.

Following numerous protests and speeches by key religious leaders in the community, the Sokoto State Police Command found guilty on May 17 some of the young men suspected to have killed Deborah in the viral video (one suspect remains at large, allegedly from the neighboring Niger Republic). In addition to ending the cycle of violence in the short term, the choice of nonviolent action is building a bridge between religious communities in the region, for a hopefully long-lasting peace.

Christians' nonviolent response to the killing

Click to watch the full video of the artist rendering. Credit:@zonastrings on TikTok.

Following the killing, religious bodies, mostly Christian associations, across the country took to various social media platforms to denounce the injustice using the hashtag #JusticeForDeborah. They used public speeches, signed public statements, mass communication through news outlets, demonstrations, symbolic public acts such as prayer and worship, and artwork to nonviolently demand justice and call for an end to extrajudicial killings and religious violence in the state.

As part of the campaign, two Christian dignitaries, Oby Ezekwesili, former education minister, and Chidi Odinkalu, an international human rights attorney, boycotted the Nigerian Bar Association conference held from May 22 to 26 in Sokoto State. As a result, the conference was pushed back to August and eventually moved to Abuja instead. For their part, the Student Christian Movement publicly condemned the killing and demanded justice on behalf of the Christian communities and the family. These were just some of the public speeches and declarations issued by Christian groups and clergies on the issue.

In response to the killing, the leadership of the Christian Association of Nigeria on May 16 called for a nationwide protest which was held on the 22nd of that month. Demonstrations were held by Christians and churches across the country to demand justice for the family of the deceased, others killed in similar circumstances, and the Christian community.

Symbolic public acts that marked the movement included prayer gatherings, as well as an emotional video on TikTok showing @zonastrings painting Deborah Samuel’s portrait to mourn the deceased and amplify the voices demanding justice.

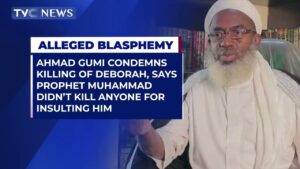

Prominent Muslims stand up against violence

Muslim leader Ahmad Gumi speaks out against the religious killing of a Christian student. Credit: TVC News on YouTube.

Islamic religious leaders too leveraged tactics such as public declarations and speeches to underscore that the killing was a vigilante act and not a just act. The Sultan of Sokoto, Muhammadu Abubakar, the spiritual leader of northern Nigeria’s Muslims, courageously condemned the gruesome murder of the female student and called for justice. Sheikh Ahmad Gumi, a popular Kaduna-based Islamic scholar, bravely made a public speech condemning the mob killing of Deborah during his teaching at the Sultan Bello Mosque, Kaduna. He declared it as an act of ignorance, and that the perpetrators would not smile in paradise. He said no one should die for insulting the Prophet.

Connecting means to ends

The episode is an important reminder of how means and ends can reinforce each other (referring to the choice between violence and nonviolent action). Nonviolent action provided an opportunity for the two religions, which on a national scale each make up half of the population, to unite in charting a course against religious violence—a scourge that has eaten deep into the societal fabric of Nigeria. Had the Christian community responded to the killing with violence, it would have been unlikely, perhaps even impossible, to win over key members of the Muslim community. After all, the goal of the campaign was to end violence—regardless of who was perpetrator and victim. The Christian minority's nonviolent response ultimately paved the way for the Muslims to join in actions against violence.

What's more, the choice of nonviolent struggle has proven a strategic one for Christian organizations and clergies across the country. It has done more than build a bridge via which allies among Muslim groups could join the movement. It also attracted the support of human rights organizations and intergovernmental organizations whose work involves countering religious violence in the country. Such parties would not have been willing to provide support for violent actors.

Building bridges for peace

The perpetrators of the vigilante killing have been imprisoned for their actions. The family of the deceased received reparations from a number of churches and organizations for their loss. Order and calm have been restored in Sokoto.

Above all, the display of collective solidarity in condemning the violence have given residents newfound hope that religion will never again be used in their community as a pretext to commit murder. But if it is, the lesson is clear: nonviolent means are effective in mobilizing communities, bridging religious divides, and fighting for justice and against impunity.

Amos Oluwatoye

Amos Oluwatoye is Research Director with Building Blocks for Peace Foundation and Research Volunteer with Metta Center for Nonviolence. An ICNC alum, he is actively involved in research, community, and international development projects focused on peacebuilding, nonviolent movements for societal change, political violence, public policy and international development.

Read More