Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by María Gabriela Mata CarnevaliMay 31, 2023

Esta entrada de blog también está disponible en español (enlace).

During an intense research stay at the Center for Conflict and Peace Studies of Hargeisa, the capital of Somaliland, in November 2022, I learned of the incredible story about how women were the protagonists of a civil resistance movement for peace that turned out to be key for consolidation of Somaliland as a separate state from Somalia (1991-1996).

What attracted my attention was, first of all, their use of poetry and songs as nonviolent actions. Yet the more I read and the more I conversed with Somalilander women, the more I came to admire their sense of fraternity—by which I mean the social bond that unites all of us as part of the human family—, which allowed them to surpass clan differences and the limitations of a traditionally patriarchal Muslim society.

In this post, I draw on a few interviews I conducted with women who participated in the movement. As we approach the next presidential Somaliland elections in July (originally scheduled for last November), we are reminded of the delicate nature of transitions to peace and democracy—and the important role of women’s power in consolidating those dynamic processes.

November 2022, Somaliland. Credit: Author.

Somalia, before Somaliland independence

In the Federal Republic of Somalia, Islam is the dominant religion, practiced by the vast majority of the population. Somalis are predominantly pastoral nomads who organize themselves into male lineage-based clans. The largest clans include the nomadic Darod, Isaq, Hawiye and Dir, and the agriculturalist Rahanwayn.

In these clans, women’s voices are traditionally considered inferior. One reason for this is that women’s clan loyalty is perceived as unpredictable because of her multiple affiliations with her father’s, mother’s, husband’s, children’s and son-in-law’s clans. Women therefore are often excluded from negotiations and decision-making forums that can affect the fortunes of the group.

The collapse of the Siad Barre era (1969-1991), marked by high levels of corruption and brutality, did not mean the end of the civil war that it had provoked. Rather, clan militias began fighting among themselves for power. This created an environment of widespread looting, a rapid increase in sexual violence and high levels of displacement.

Since then, Somalia has lived in an uninterrupted state of disorder, violence and fragmentation, with an increasing influence of religious fundamentalist movements. For all this, it has been considered a “failed state”—for The Economist, “the most failed state”.

Some clans chose to escape this chaos. In May 1991, the Isaq and its allies, the Dir, declared an independent Republic in the northwest with the capital in Hargeisa. It was not easily implemented. Women were at the center of the years-long process, first as the main victims of the instability and later as peace builders.

Their weapons: words.

Poetry and song as nonviolent actions

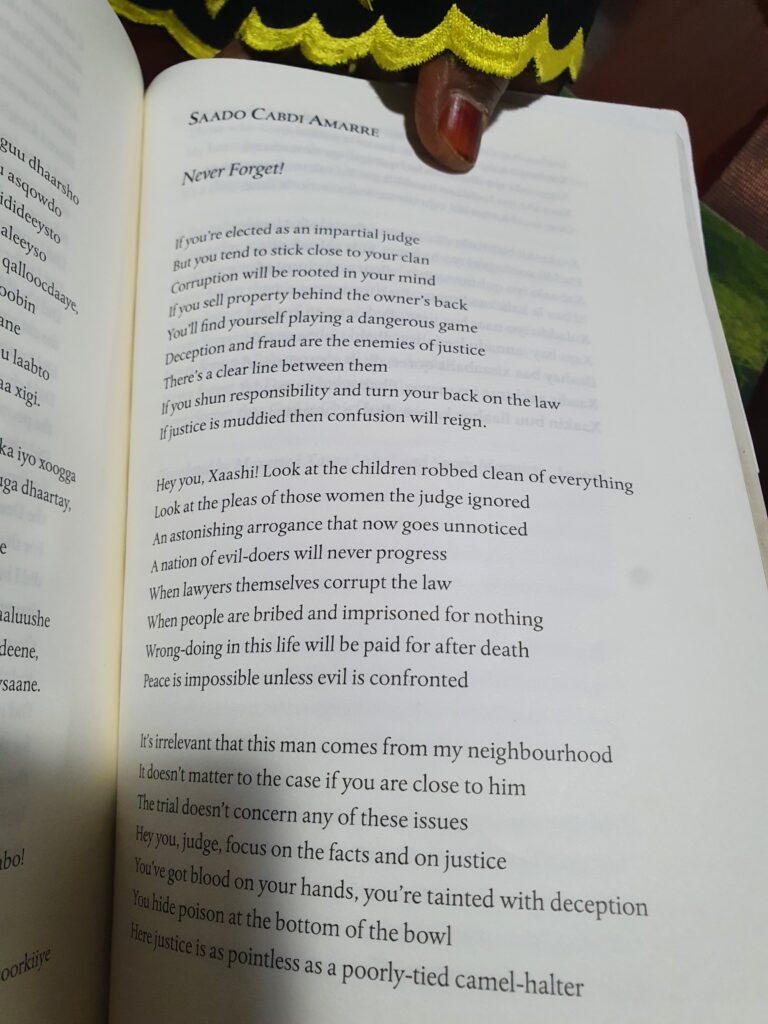

Saado Cabdi Amarre, a Somalilander poetess who wrote the poem "Never Forget!" (poem below). Credit: Author.

The Somali civil war, with the clan as shield and sword, placed women at the center of the pain. But women took this pain and turned it into the seed of peace. They leveraged their multiple affiliations as an asset to collectively resist violence, instead of accepting this as a fault. Their actions compelled their men to sit together, discuss a way to end the conflict and turn the page.

The women’s nonviolent struggle for peace advanced first in Burao (1991), then in Berbera (1992), Boroma and Erigavo (1993), and finally in Hargeisa (1994-96). Women’s important contributions to ending violence and promoting peace included a wide variety of actions from the nonviolent conflict repertoire: formal appeals to warring parties, demonstrations, petitioning of politicians and elders, and provision of logistical and financial support to peace processes.

Characteristically, the women used poetry and song, in particular a light style called burumbur, regardless of the fact that memorization/recitation is a predominantly male occupation. They also used allabari, a type of collective prayer to which they gave a new meaning.

Through poetry and song, the women conveyed messages like: “My clothes have caught fire by both ends”; and “Why is this section of the town not speaking to the other? Why is my left arm not talking to my right? Why is my brother fighting my son? Why is my husband fighting with my brother?” These metaphors and appeals of logic encouraged parties to the conflict to set down their weapons and sit together.

If we consider poetry as an expression of a particular worldview, the Somalilander poetesses challenged male hegemony not only at the artistic level but also in the production of knowledge—by taking a stand against the status quo with solid arguments.

The incredible thing is that they did so in the very midst of violence.

Tirsit Yetbarek at the Hargeisa Cultural Center, November 2022. Credit: Author.

Women resisting in the midst of civil war

In Burao, after talking to the elders and without waiting for a response, women immediately took action. As one of my interviewees explained, around 300 women tied white bands around their heads as a sign of mourning (white symbolizes anger or sorrow in Somali culture) and then marched back and forth between the two armed groups singing burumbur. They urged combatants to remember the bad times they and their families had gone through.

As they did this, men stopped firing. The men were ashamed of the sorrowful songs being addressed to them. Within a matter of days, a cease fire was put in place.

Yasmin Omar H. Mohamoud, Amal Ali, Hana Mohamed Abdi and Ayan Yusuf at the women leaders workshop in Hargeisa, November 2022. Credit: Author.

Women leaders workshop, Hargeisa, November 2022. Credit: Author.

In Berbera, women intervened to end hostilities between sub-clans of the Isaq clan by organizing demonstrations and allabari. They submitted a statement to the government, along with copies to the press and the parties in conflict. They demanded that the war between the sub-clans end as soon as possible, without international military intervention. The delivery of the declaration was accompanied by a demonstration and the women leaders refused to leave the building until a peace agreement was signed.

The Boroma Grand Conference on National Reconciliation took place from January to May 1993. The event was decisive in the consolidation of the Somaliland state. One hundred fifty chiefs took part with voting power. Only 10 women representing two women’s organizations attended (the Somaliland Women's Development Association and the Somaliland Women's Organization), and this only after intense lobbying. They courageously presented their views through speeches, pamphlets, poems and songs, but tradition denied them the right to vote.

Despite their efforts, women could do little to prevent the outbreak of the so-called Hargeisa war that divided the population of the capital and sent more than half of them into exile in Ethiopia. Only in 1996, after innumerable marches and allabari, a national conference restored peace in Somaliland, opening the way to the formation of a democratic government with parties that by law do not identify themselves with clans. Women did attend but in a small number and only as observers.

Credit: With students at the Hargeisa Cultural Center, November 2022. Credit: Author.

Fraternity towards the future

Fraternity can nurture and shape civil resistance. The nonviolent struggle for peace in Somaliland succeeded largely because of the women’s sense of fraternity in their creative grassroots work.

Yet, democracy without inclusion is not democracy. And peace without equality is not peace. Despite their leading role in nation-building and peacebuilding, women are still not fully integrated in the different decision-making bodies in Somaliland.

Looking ahead, the next presidential election is scheduled for this July, having been pushed back from November 2022 by current Somaliland president Muse Bihi Abdi. Women have the opportunity to join forces again to push for democratic consolidation and the abolishment of discriminatory laws and traditions. For sure, their deeply rooted experience at the intersection of nonviolent resistance and peacebuilding—and above all, their embrace of fraternity—would serve them as strong assets in any renewed fight for women’s rights and true peace.

María Gabriela Mata Carnevali

María Gabriela Mata Carnevali is a Venezuelan researcher on International Relations with a focus on the Global South and rule of law. She completed her higher education degrees at El Colegio de México and Loyola University, Chicago (USA) and is currently enrolled in a Ph.D. program at the Università degli studi di Palermo in Italy. María served as a moderator of ICNC’s People Power online course in 2019 and 2020. Her motto is “Stand with human rights. Stand with peace.”

Read More