Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Janjira SombatpoonsiriJanuary 04, 2021

Thailand’s ongoing democratic revolt is historically unprecedented. Not only does the movement systemically challenge deep-rooted autocracy, but through decentralized organization and a variety of creative tactics, it has been consistently nonviolent. The movement has emerged against all odds, both harsh repression on the one hand and the disruptive impact of the pandemic on the other. Whether Thailand’s people power will succeed in pushing back against autocracy sheds light on the future success of nonviolent struggle against the current global wave of autocratization.

Movement trajectory

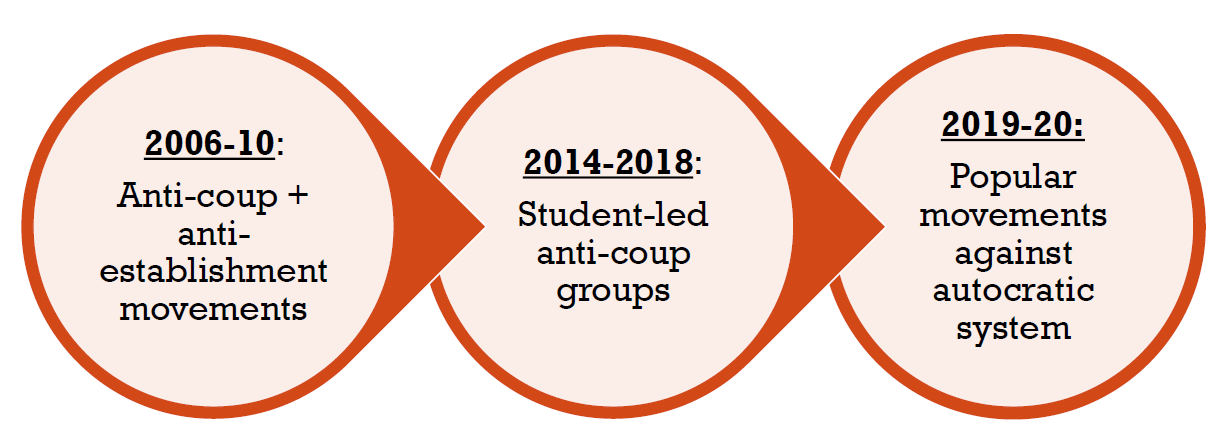

Understanding the significance of Thailand’s democratic revolt requires situating it in the decades-long arch of popular resistance against autocratic encroachment in the country. Thailand’s longest democratic rule took shape after the 1992 unarmed insurrection. But existing autocratic networks survived this democratic change. Meanwhile, the new democratic order empowered new elites who in turn impinged on these networks’ spheres of influence. In response, the old guards coalesced to overthrow Thailand’s democracy in 2006 and again in 2014. Civic coalitions against the autocratic establishment (comprising the palace and the army) emerged in this light. In 2010 the struggle reached its zenith, but protesters’ oscillation between nonviolent tactics and vandalism was met with brutal crackdown.

On November 14, 2020, protesters scaled a Bangkok monument to unfurl a giant banner scribbled with anti-government slogans, while flashing the three-finger salute, the anti-dictatorship symbol of the movements. Source: Matichai Teawna & 101.world (with permission).

However, student activism was rejuvenated, against the odds of military rule, which lasted from 2014 to 2019. On the one hand, military autocracy shrunk civil society spaces through legal and digital repression, while undermining the rule of law and widening income gap. As a result, many youngsters have become increasingly disillusioned with the system. On the other hand, this gloomy prospect has compelled young people to organize and fight for their future, both in the digital arena and at the grassroots level.

The current wave of civil resistance represents a new breed of pro-democracy struggle in Thailand that goes beyond removing sitting autocrats by promoting systemic changes that address the interplay of autocracy, inequality, and exclusion in the country. Accordingly, protesters’ demands include not only the Prime Minister's resignation, but also the democratic amendment to the constitution, especially the abolition of the unelected senate, as well as the reform of deeply politicized monarchy in line with constitutional monarchy.

The following chart shows the historical trajectory of civil resistance against autocracy in Thailand, widening from focusing on anti-coup to countering autocracy as a system.

Source: Author.

Movement learning over the past decade

The 2019-20 movements, operating under the umbrella organization known as Khana Ratsadon 2563, or People’s Party 2020, have learned from their predecessors’ mistakes in terms of organizational style and tactics. Having been continuously harassed by the junta, activists are convinced that traditional organizational structure is ineffective. They are opting for decentralization based on loose coordination between student groups and allied civic organizations.

When the arrest of leading activists intensified after mid-October 2020, the movements announced that “we are all leaders today,” setting the stage for proliferating nonviolent protests organized by collective individuals across different localities. As of this writing, there have been nearly 462 protests since January 2020. These seemingly autonomous cells promote their specific agendas, from gender equality and labor rights to reforms of Buddhism, while framing these agendas in terms of equality and inclusion in line with movements’ overarching demands to democratize the country.

Decentralization corresponds to the hybridization of online and offline organizing that characterizes the movements’ tactical creativity. Twitter hashtags have been created to publicize protest events and galvanize ideas for ‘hip’ and ‘cool’ nonviolent actions. Lately, Twitter has served as a major platform for mobilizing crowds to counter arbitrary arrests.

This year’s movements sometimes rely on cheeky and carnival-like actions to sustain their momentum and disarm the authorities. For instance, in July 2020, the Bangkok metropolitan authorities placed numerous flower pots around the Democracy Monument to obstruct mass gatherings there. Activists wittingly responded by inviting people to visit this urban flower garden and collectively shouting “such a beautiful garden” ten times.

As the police-protester standoff has recently become regular, street art exhibitions, parades and festivities are organized to lighten protesters’ mood while conveying serious messages. The movements are aware that the outbreak of violence would play into the hand of autocrats and their mass supporters.

On November 17, 2020, protesters used rubber canvases and rubber ducks to defend themselves from police water cannons. Source: Matichai Teawna & 101.world (with permission).

Global implications?

Current protests in Thailand are often compared with the 2019 Hong Kong uprisings in terms of horizontal organization and tactical flexibility. But the Thai case is distinct not only because of different political contexts, but most importantly protesters’ learning curve regarding nonviolent discipline.

First, the movements have learned the strategic significance of nonviolent discipline from past experiences of crackdown and coup cycles at the advent of street clashes. This awareness has so far prevented violent escalation between pro-democracy protesters and the police, and between the former with royalist counter-demonstrators.

Second, activists can maintain nonviolent discipline mainly due to their organizing of festive activities and humorous actions together with the deployment of nonviolent peacekeepers. Noteworthy, while nonviolent peacekeepers are mostly male, many organizers and participants are female and queer. They shape the festive atmosphere, projecting the movements’ friendly image.

Lastly, leading organizers seek systemic changes. They are aware that this will be a long-haul struggle and such requires nonviolent persistence. Here is a critical lesson for movements in the age of autocratization. Quick fixes such as replacing an ousted autocrat with an electoral regime do not sufficiently address entrenched authoritarian structures and political culture. The future of pro-democracy struggle is this long, winding process to overcome the enduring influence of autocratic networks in order to deepen democracy.

Join the conversation on Twitter @civilresistance, hashtag #ICNC2020Top10

Check out our "Top 10 Civil Resistance Stories of 2020, Looking Forward" countdown, with new posts rolling out every Monday from December 14, 2020 through February 15, 2021.

Janjira Sombatpoonsiri

Dr. Janjira Sombatpoonsiri is currently a research fellow at the Institute of Asian Studies, Chulalongkorn University in Thailand, and the German Institute for Global and Area Studies. Her research focuses on civil resistance, civil society’s pushbacks against autocratization, and digital repression in Asia.

Read More