Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Maciej BartkowskiJune 13, 2018

Esta entrada de blog también está disponible en español: (enlace).

“[The regime] controls empty stores, but not the market; the employment of workers, but not their livelihood; the official media, but not the circulation of information; printing press, but not the publishing movement; the mail and telephones, but not communication; and the school system, but not education."

- Wiktor Kulerski, Polish anti-communist activist on the impact of the nonviolent Solidarity movement on Polish society

In 1973, the pioneering scholar Gene Sharp set the standard for classifying methods of nonviolent action, famously documenting 198 of them and dividing them into three broad categories: protest and persuasion, noncooperation, and nonviolent intervention.

Forty-five years later, a forthcoming ICNC publication, Revisiting the Methods of Nonviolent Action by Michael Beer of Nonviolence International, will take on the formidable task of updating, expanding, and reclassifying the universe of civil resistance methods. Among its many contributions, the book introduces an entire new category called Creative (Constructive) Intervention, defining it as “direct action that models or constructs alternative behaviors and institutions or takes over existing institutions.”

It is well known that movements—from American colonists nonviolently resisting British rule (1765-1775), to the Indian Independence Movement (1920s-1940s), to the Solidarity movement in Poland (1980-89)—engaged in extensive alternative institution-building. Yet, in his groundbreaking list of 198 nonviolent methods, Sharp catalogued only three vague examples: alternative social institutions, alternative economic institutions, and dual sovereignty/parallel government (numbers 179, 192 and 198 respectively). Furthermore, Sharp claims these three examples all fall under his category of “nonviolent intervention”, rather than identifying them as part of an independent category of nonviolent action. Proposing a new category of Creative (Constructive) Intervention that specifically captures the many forms of alternative institutions reflects the true significance that these methods have for civil resistance scholarship and practice.

Maria Skłodowska, known as Marie Curie Sklodowska, co-discovered Radium and Polonium and was the first female Nobel prize winner in physics in 1903 and the only one who won two Nobel prizes in two disciplines (the second one in 1911 in chemistry). As a young girl, Sklodowska attended the secret ‘Flying University’ in 19th century partitioned Poland that was established as part of the Polish constructive resistance against Tsarist Russia’s Russification policies. Image source: Wikipedia.

Alternative institution-building is understood broadly as the process undertaken by organized civilians to establish new practices and organizations that are parallel to and aim to challenge dominant socio-economic, cultural, and political structures viewed as unjust and oppressive. They may be legal, semi-legal, or illegal. Some examples include alternative schools; health clinics; publishing houses; media outlets; political parties; financial, economic, and social institutions; agricultural cooperatives; proto-political and governing institutions, and community service organizations—plus all the practices within these institutions that brought them to life in the first place.

Model of Change

The model of change propelled by alternative institution-building is based on societal transformation, self-organization, liberation, and prefiguration. These qualities also define what a self-organized resistant polity is about:

1. Societal transformation: Alternative institution-building is not about launching a direct challenge against a repressive regime with the goal of bringing it down. Instead, it aims, first and foremost, at transforming society from within by building stronger communal bonds and networks, increasing awareness of shared culture, history, common identity, and destiny, and by helping articulate grievances, demands, and solutions.

2. Societal self-organization: Through work aimed at impacting its very foundation, the society transforms itself into an independent and mobilized civic polity that is self-organized in economic, social, cultural, and educational spheres, and that ensures daily delivery of services to its members.

3. Societal liberation: Through its transformation and self-organization, the society gradually but inexorably liberates itself from the control of a repressive regime.

4. Societal prefiguration: Engaged in independent practices, a self-organized resistant polity reimagines itself in the mode of the society it desires once oppressive structures are gone. In this sense, alternative institutions foreshadow the society to act as if it were free, before it formally becomes free.

Characteristics of Alternative Institutions

Alternative institution-building also carries four key characteristics of being:

1. Seemingly apolitical: It often relies on apparently apolitical, innocuous, day-to-day ordinary activities in social, cultural, or economic spheres to organize an independent society not necessarily seen by the authorities as constituting any immediate political threat.

2. Less risky: In contrast to street actions such as protests or demonstrations, alternative institution-building avoids unnecessary exposure, does not give the adversary an easy pretext to fire upon participants, and does not put massive numbers of people into visible harm’s way.

Russian samizdat and photo negatives of unofficial literature in the USSR. Moscow. Image source: Wikipedia.

3. Long-term: Alternative institution-building does not happen overnight and is in fact a representation of a long-term approach to what is often a generation-long struggle, requiring resilience and patience.

4. Solidarity-driven: How and to what extent alternative institution-building permeates a society depends on how successful solidarity (e.g. humanitarian, legal, financial, or even vocal expression of human empathy) across different societal members and groups is established and dispersed through such institutions.

Types of Alternative Institution-Building

At least five general types of alternative institution-building can be identified, based on their overall and predominant goals. Some of the types overlap, but their primary goals also make them distinct from one another:

1. Self-sufficiency and self-reliance where the predominant goal of alternative institution-building is the long-term socio-economic survival of a nation that experienced a prolonged and repressive foreign occupation, colonial domination, or domestic totalitarian rule. One example of this is the Polish organic work in the second half of the 19th century, which aimed at establishing indigenous financial institutions and social and economic cooperatives to ensure national subsistence. In particular, it pushed against the German empire’s land grab and economic colonial expansion into its partitioned Polish territory.

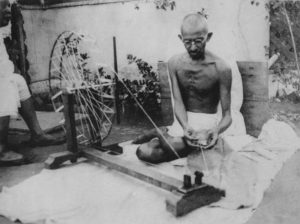

Gandhi spinning cotton in India in the 1940s. Image source: Wikipedia.

A second example of this is the constructive program that Mohandas Gandhi articulated and advanced during the Indian independence struggle against British colonial rule. The constructive program was represented by a charkha or a spinning wheel, among other symbols. Gandhi chose this symbol to call on his compatriots to make their own homespun cloth and thus become self-reliant and economically independent of the British.

A contemporary example could be the alternative economic markets in North Korea illustrating that even closed totalitarian systems are not impervious to citizen-led alternative institution-building, even when more direct actions such as protests, strikes, or demonstrations are not possible.

2. Socio-cultural self-defense where the central goal of alternative institution-building is to ensure that a nation or people successfully defends its socio-cultural fabric against protracted occupation and powerful denationalization forces. For example, Tibetans embarked on transformative cultural resistance to protect their language and culture against “Chinesation” while Estonians embraced folk songs and singing as a way to push back against Russification and defend their Estonian culture. West Papuans relied on Catholic churches and Christianity to grow and guard their culture and identity against oppression from the Indonesian government and its security forces. Other examples are the Poles resisting communism and the Kosovars establishing a sophisticated alternative educational system to strengthen their ethnic community and guard against the deculturization policies of Milosevic’s Serbia.

3. Self-rule where the dominant goal of alternative institution-building is to set up and run functioning alternative governance to achieve complete political liberation. An example could be the American colonies refusing to obey British colonial structures and either nonviolently seizing existing institutions (e.g. judicial system) or building new governing bodies (e.g. political congresses) and thus winning their de-facto independence even before the war broke out in 1776.

4. Self-organization and autonomy where the prevailing goal of alternative institution-building is to reclaim a specific space, usually a village, a town, or a neighborhood, from violence perpetrated by violent state or nonstate groups. Examples of the towns of San Jose de Apartado in Colombia, the Chinese town Wukan in 2011, and Cheran in Mexico show how mobilized locals seize and organize their village territory in order to establish village autonomy. They set up their own governance structures and make collective decisions on a wide range of issues important to the townspeople: provision of security, delivery of basic services, dealing with armed groups, etc. At the same time, their institutions remain at least formally under the national and regional state structures.

5. Self-sustainability where the main goal of alternative institution-building is to ensure an effective, usually short-term occupation of a specific symbolic space. For example, during the 17 days of the Egyptian revolution in January and February 2011, people captured the main square in the capital, Tahrir square, and set up a tent city, health clinics, garbage collection services, public toilets, newspaper stands, spaces for political discussion and praying, systems for delivery of water, food, and cooking gas, and checkpoints to prevent infiltration of weapons and government agents. In Ukraine, during the Orange (2004) and Euromaidan (2014) revolutions, where freezing temperatures could easily exhaust and dissuade protesters, an impressive network of tents and interlinked food, hot water, and electricity services, psychological and medical aid, together with impromptu theater sketches, university-type lectures, and music concerts created a self-sustainable life on the main square of the capital, Maidan, for hundreds of thousands of people.

Functions and Impact of Alternative Institution-Building

Alternative institutions as part of a civil resistance struggle can perform various functions and generate different impacts. They can help:

- Educate and shape collective identity and consciousness.

- Initiate a broader civil resistance movement by presenting an organized community as a seemingly noncontroversial, nonconfrontational, benign force that might be either allowed or ignored by repressive powers.

- Build organizational, material, skill-based capacity of the resistance to continue oppositional activities and undertake new, possibly more disruptive, mass-based methods of civil resistance (strikes, demonstrations, boycotts) in the future.

- Create informal structures and networks and develop collaborative and consensus-seeking interactions among different people.

- Establish coalitions, even across ideologically diverse groups united around the goal of providing basic services and self-governance.

- Create social capital in a networked community and society as a foundation for democratization in the future.

- Facilitate reducing and sharing risk, establishing mutual trust, and lowering people’s fear of participation in a movement.

- Deconcentrate or diffuse power among various groups and decentralize movement structures.

- Train people in and facilitate democratic decision-making based on a consensus or negotiated compromises.

- Develop autonomy, self-reliance, solidarity, and mutual aid systems.

- Increase movement resilience against repression.

The ultimate impact of alternative-institution building is the establishment of a self-organized resistant polity. A perfect encapsulation of such polity is the quote by one of the Polish Solidarity activists, Wiktor Kulerski, who thought that Poles’ continued nonviolent organizing and resistance against communism will ultimately lead to the day when:

[The communist regime] “controls empty stores, but not the market; the employment of workers, but not their livelihood; the official media, but not the circulation of information; printing press, but not the publishing movement; the mail and telephones, but not communication; and the school system, but not education."

Maciej Bartkowski

Dr. Maciej Bartkowski is a Senior Advisor to ICNC. He works on academic programs to support teaching, research and study on civil resistance. He is a series editor of the ICNC Monographs and ICNC Special Reports, and book editor of Recovering Nonviolent History. You can follow him @macbartkow