Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Steward Muhindo KalyamughumaAugust 10, 2023

Lisez cet article en français ici (traduction par Ange Akemani).

"With good planning, well-controlled financial packages and good organization of worksites across the country, we are capable of building more than 5,000 kilometers of modern roads over the next five years." So declared Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) president Felix Antoine Tshisekedi on March 2, 2019, shortly after replacing incumbent Joseph Kabila.

In 2019, LUCHA shifted its priorities toward citizen awakening with the launch of their first Fatshimétrie report. Credit: Lucha RDC Facebook page.

Tshisekedi had made similar promises during the election campaign, on the theme of transforming the DRC, a potentially wealthy country whose citizens face insecurity, poverty and poor access to basic social services such as schools, water, healthcare and electricity.

In the DRC, political leaders like Tshisekedi have often made promises of change. His predecessor Joseph Kabila was elected in 2006 and 2011 on the basis of attractive and promising programs, which in the end hardly materialized in the daily lives of the Congolese people.

Government accountability is an intricate ideal to struggle toward as a nonviolent movement. Public opinion and public narrative are key; and data are too. That’s why a Congolese nonviolent movement, LUCHA, began publishing in 2019 an annual report compiling metrics to document promises that politicians make to—and break for—the Congolese people.

A tool for holding elected representatives accountable

The citizen movement Lutte pour le Changement (Struggle for Change, or LUCHA) was founded in 2012 by young Congolese frustrated by the dramatic situation in their country. LUCHA pursued nonviolent resistance to inform citizens and fuel their outrage, as well as to hold those in power more responsible and accountable.

The Fatshimétrie reports are available via this website.

In its first 11 years of struggle, the movement, which was founded in Goma (North Kivu), has spread to 50 towns across the country. Its social and political influence has grown steadily. Having struggled valiantly for the departure of Joseph Kabila, who wanted to remain in power in violation of the constitution, LUCHA is now committed to holding "elected officials" accountable for their political promises and commitments.

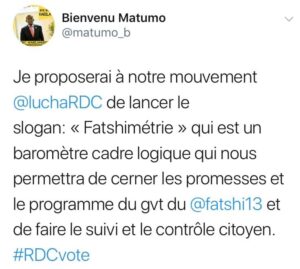

One of the tools used for this is called Fatshimétrie. The term “Fatshimétrie” is a blend of Fatshi, drawing from the names of President Felix Antoine Tshisekedi, and métrie, which refers to measurement or metrics in French. Fatshimétrie is a barometer for assessing the level of fulfilment of commitments and promises made by the head of state to transform the DRC. The Fatshimétrie campaign was launched on January 31, 2019, one week after Tshisekedi’s accession to power.

Using data to bring people together

@matumo_b: "I propose that our movement LUCHA RDC launch the slogan, "Fatshimétrie", a logical framework barometer that will allow us to dial in on government promises and program and to follow up with citizen accountability." Credit: LUCHA RDC.

The Fatshimétrie campaign emerged in reponse to political corruption. The independent national electoral commission had declared Tshisekedi winner of the December 30, 2018 presidential elections. However, several analysts and credible observers, as well as published leaks from the electoral commission's own servers, had indicated otherwise.

The concept was proposed by comrade Bienvenu Matumo, a DRC graduate of the National School of Administration and a researcher in the social sciences at the University of Paris 8 in France. Inspired by the Mali-Mètre in Mali, the term Fatshimétrie emerged based on a discussion with two Congolese journalists in Paris, Matumo told me.

As part of the Fatshimétrie campaign, LUCHA publishes periodic thematic reports on the country's governance, with reference to the commitments and promises made by the Tshisekedi administration. Based on proven data and backed by a rigorous methodology, Fatshimétrie reports have the advantage of capturing popular sentiments beyond any partiality. They show the huge gap between promises made and actual governance measures and results that the Tshisekedi administration achieved. In this way, Fatshimétrie fills the information vacuum, which politicians easily exploit in order to deceive and divide the people.

Stimulating public debate and good governance

First Fatshimétrie report launch in 2019. Credit: LUCHA RDC Facebook page.

Unsurprisingly, Fatshimétrie reports stimulate public debate on governance and push public authorities to become more accountable to citizens. The 2022 report shows that the DRC’s overall situation continues to deteriorate under Tshisekedi’s leadership. It generated considerable media attention and fierce criticism from supporters of the incumbent government, who undoubtedly have their eyes set on the December 2023 elections.

However, the campaign’s greatest achievement is that the tool is now a way to demonstrate popular, non-partisan demands and to show the extent to which the Tshisekedi administration is not keeping its promises or fulfilling political commitments made. The #Fatshimetrie hashtag on Twitter and Facebook is a good illustration of just how much the Congolese people have embraced this campaign. In an aspiring democracy like the DRC, being able to mobilize citizens to hold leaders accountable helps stimulate good governance.

Impacts, challenges, next steps...

Fatshimétrie was not easy for LUCHA to implement, given the technical research, writing and coordination required before making the reports public. Within LUCHA, we have several working groups, including one devoted to preparing the report every year. Within the working group, we work in partners to each compile and analyze data on a specific theme, like security or development. Data collection takes place little by little throughout the year.

We have two main sources of data. The first is our trained field researchers, who are in different parts of the country. The second type of source we have includes NGO reports (like Human Rights Watch) and official government data. In the DRC, we have the right to information, and usually it's feasible to get official stats on the themes we focus on. Civil servants are generally receptive to our requests for data; perhaps unsurprisingly, they are inclined to do their best to help.

Nevertheless, we do encounter some obstacles in our working group. Ideally, we would benefit from more training, in particular for field research. In addition, all the work is volunteer-based and involves a great deal of coordination.

Despite these capacity-building needs, the Fatshimétrie campaign has already proven an impactful tool in the fight against political and financial corruption, which is widespread in the DRC and in many African states. The teamwork that is necessary for producing each report reinforces movement unity and, quite simply, gives us something to be proud of.

But change in the DRC and the fight against corruption require much more than reports. It's up to Congolese citizens to mobilize to defeat and sanction corrupt political actors. The modest success of the Fatshimétrie campaign can serve as a foundation on which to build our nonviolent resistance, especially with the December 2023 elections in sight as a strategic opportunity to be seized.

Steward Muhindo Kalyamughuma

Steward Muhindo Kalyamughuma is a Congolese activist with the nonviolent, non-partisan citizen movement LUCHA (Lutte pour le Changement, Struggle for Change), and a researcher on human rights and armed conflict at the Centre de Recherche sur l’Environnement, la Démocratie et les Droits de l’Homme (CREDDHO).

Steward Muhindo Kalyamughuma est activiste Congolais du mouvement citoyen non-violent et non-partisan LUCHA (Lutte pour le Changement) et chercheur sur les droits humains et les conflits armés au Centre de Recherche sur l’Environnement, la Démocratie et les droits de l’Homme (CREDDHO).

Read More