Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Farai Maguwu and Gabriel DayleyMay 28, 2019

In June 2018, residents of Marange—a region in Zimbabwe known for one of the world’s largest diamond deposits—planned a major demonstration at the Zimbabwe Consolidated Diamond Company (ZCDC) site of operations to demand justice for gross human rights violations perpetrated by the company and government since mining began in 2009. Over the past several years, private and state security forces acting on ZCDC’s behalf have beaten, tortured, and killed artisanal miners and community members. In addition, the company has grabbed land and polluted the environment in resource extraction that has failed to benefit the people of Marange.

These community-led resistance efforts have been supported by the Centre for Natural Resource Governance (CNRG), a Zimbabwe-based civil society organization that promotes sustainable and humane natural resource governance. CNRG and a community trust registered in Marange by the NGO to coordinate community resistance have helped the movement gain visibility and popular legitimacy to rise up against ZCDC’s destructive mining practices. The movement has used a mix of civil resistance and institutional methods, including a series of street actions to call attention to ZCDC’s abuses and to pressure for changes in how diamond mining is conducted in their community; petitioning the Zimbabwe parliament and the Kimberley Process; and shaming the government and the mining company.

However, late last year, information surfaced that three CNRG board members had been co-opted, or bought off, by ZCDC. These board members had attempted to dissuade activists from participating in the June 2018 protest and to convince activists to adopt a favorable image of ZCDC. Later, they were observed spending unusual amounts of money after a long unexplained absence from the movement’s activities.

Two Methods of Co-optation

Co-optation is a concern for any movement gaining enough momentum for traditional powerholders to take notice. The term co-optation refers to the process whereby powerholders appropriate a movement's people or ideas in attempt to weaken the movement. One common method to achieve this is buying off moderate subgroups in a movement in order to convert them into powerholders’ agents (which is what happened in Marange). Consider, for example, the US-based Fair Labor Association (FLA), a watchdog organization created by the Clinton administration in response to student activism against sweatshop labor in the 1990s. FLA funding comes in part from the very companies it is supposed to monitor. In this case, powerholders secure “collusion or compromises by reformer activists that undercut the achievement of critical movement goals,” in the words of activist Bill Moyer.

Another co-optation method involves appropriating movement ideas to dilute their effectiveness as a rallying tool. For example, consider how businesses often adopt rhetoric from the environmental movement, appropriating “words and concepts, such as ‘sustainability,’ ‘green,’ or ‘organic food,’ but only to confuse the public and reduce the effectiveness of the movement’s use of the terms,” according to Moyer.

The impact of these kinds of measures can be very detrimental for a movement. Based on interviews with Egyptian activists, Nadine Sika observes that co-optation:

“is an instrumental tactic for the regime in two manners: first it creates internal struggles within the movements themselves, which adds to their fragmentation. Second, it facilitates a regime’s repression against protest movement actors. This creates more fragmentation in addition to deterrence to the development of new protest movements and protest activities.”

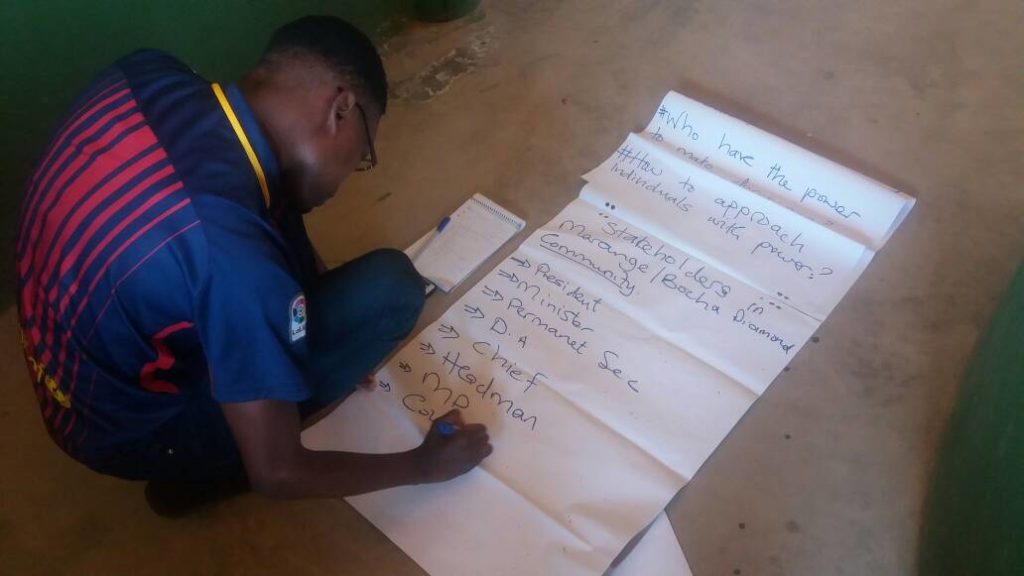

Community meeting in Marange, Zimbabwe. Source: CNRG, 2018.

How to Fight Back When Co-optation Is Suspected

A natural response to suspected co-optation may be for activists to name and shame persons who were bought out, labeling them as traitors who cannot be trusted. Yet there might be a more shrewd way of handling co-optation: discreetly isolate, then disarm, then show them the exit.

When word began spreading in the Marange community about the co-opted board members, CNRG and the community trust didn’t join in accusing them. Instead, CNRG staff met with the trust’s other nine board members and several traditional community leaders to gather more information. After confirming what was rumored, movement leaders restructured the community trust to provide a clearer division of responsibility between the board of trustees and the secretariat in charge of organizing movement activities.

Instead of seeking to remove the co-opted individuals from the board of trustees altogether, CNRG staff reminded them that their role as board members was policy making for the trust, not directly managing the secretariat’s planning of movement activities. The other board members agreed to abide by this mandate. The trust then expanded the secretariat to include coordinators from each village in Marange, allowing the latter to operate with greater independence and decentralization.

In clarifying the division of responsibility between the board and secretariat, CNRG staff emphasized the significance and prestige of serving on the board, which elevated the co-opted board members’ sense of importance as movement leaders while neutralizing their ability to undermine movement activities. To maintain their sense of importance, they continued to be included in small ways in subsequent months. For example, in November 2018, the secretariat mobilized a commemoration of the Marange killings that attracted more than 6,500 people, and one of the three co-opted board members was asked to give welcoming remarks. Another was sent to South Africa for an international conference on resource extraction.

After months of carefully managing the potential harm that the co-opted board members could have caused, in December 2018, the movement felt ready to ask them to step down. Facing exit, they became aggressive and again tried to disrupt movement activities, but their capacity to damage the movement had been greatly diminished. At this point, the more they tried to disrupt, the more they alienated themselves from the community.

Movement participant in Marange. Source: CNRG, 2018.

Ultimately, if you suspect that someone in your movement has been co-opted, examine your context and the options available to you before taking action. Be mindful of your initial emotional response when you begin suspecting co-optation. Give time to allow emotions to settle before considering what to do so that a skillful response can be formulated, rather than reacting in the heat of the moment. In some cases, movement leaders might decide that naming and shaming is the way to go. But in many cases, a more subtle response, like the one described here, may be more effective at dismissing co-opted members—without compromising a movement’s integrity.

Farai Maguwu

Farai Maguwu is the founding Director of the Centre for Natural Resource Governance (CNRG), a leading organization working on improved governance of natural resources in Zimbabwe. In 2011, Human Rights Watch honored him with the prestigious Alison Des Forges Award for Extraordinary Activism. Farai is a PhD candidate at the School of Developmental Studies, University of Kwazulu Natal and holds two Masters.

Read More

Gabriel Dayley

Gabriel Dayley is the Executive Director of the Shambhala Meditation Center of Washington, DC and Chief Editor of The Arrow: A Journal of Wakeful Society, Culture & Politics. He completed his MA in International Peace and Conflict Resolution at American University. Gabe works at ICNC in support of Global Field Initiatives.

Read More