Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Amber FrenchAugust 08, 2017

Click here to download video transcript (PDF)

When I sat down with Mohsen Sazegara, exiled dissident, journalist and writer from Iran, to talk about civil resistance in his origin country, I got an unexpected lesson in physics.

A former student of mechanical engineering, Sazegara found a way to apply the conservation of energy principle to the longstanding democracy movement of Iran:

“I believe that these types of movements like the Green Movement, they may be defeated in one stage, but the energy doesn't go anywhere. Based on the conservation of energy principle, it will continue, and this is what has happened in Iran. [Sooner or] later it comes out.”

Until witnessing first-hand the power of civil resistance during the Iranian Revolution (1977-1979), also known as the Islamic Revolution, he had no idea that nonviolent action was a viable form of political struggle.

Today, he is a main fixture in the pro-democracy diaspora, engaged in such impactful actions as producing daily videos in Farsi for activists about nonviolent tactics and strategies and translating civil resistance materials into Farsi.

He’s also a discerning student of the ongoing democracy movement in Iran: its history, challenges and prospects for change.

The Road to Democracy

With a relatively well-documented civil resistance history dating back over a century, Iran serves as one of the rare longitudinal case studies in our field. Reflecting on the Constitutional Revolution during the first years of the 20th century, the Islamic Revolution, and the 2009 Green Revolution, Sazegara pointed out: “The people succeeded to confront the dictatorship or bring it down, but the movements always ended in the same result. The dictatorship returned—it was reproduced—and the road to democracy was blocked.”

This was certainly the case in the most recent mass nonviolent uprising, the Green Movement, which was triggered by widespread suspicion of election fraud after the government claimed that Mahmoud Ahmadinejad had won the 2009 presidential election. Days of sustained and courageous nonviolent mobilization followed, and shook the government to its core, with some arguing that the movement nearly succeeded in ushering in government transition. However, as Sazegara points out, the movement lacked some key aspects of unity and strategic planning, and ultimately succumbed to violent repression ordered by the state.

Comparing the Green Movement and the Islamic Revolution

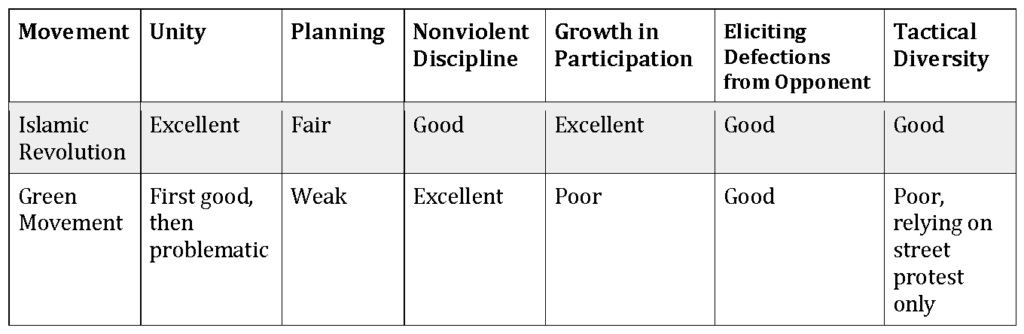

Drawing from The Checklist for Ending Tyranny by Peter Ackerman and Hardy Merriman, Sazegara laid out a comparison of the Green Movement and the Islamic Revolution, the main points of which are summarized in the table below:

Source: Author

According to Sazegara, the initial unity that the Green Movement enjoyed gradually diminished. Leadership was not knowledgeable about civil resistance strategy and tactics and was therefore ill-equipped to decisively plan and implement a grand strategy—a key factor in the effectiveness of nonviolent movements. Another major pitfall was a lack of tactical diversity and innovation. Choosing diverse and innovative tactics can play an important role in helping a movement withstand largescale repression and stay one step ahead of the regime on the nonviolent battlefield.

Sazegara did, however, praise the nonviolent discipline of the Green Movement, saying it was “fantastic during all the months of the movement. People believed in that and kept that discipline.”

Challenges and Prospects for Change

The obstacles that Iranian activists face on their road to democracy were very clear to Sazegara—as is a possible way to strategize for success:

“Civil society of Iran, amongst the nurses, journalists, teachers, laborers, women, environmental activists, in many parts of the society they have their own tactics and try to oppose based on their goals with this regime. I think that our main problem is now how to join all of them together. All these movements should gradually join each other based on one or two main goals, like a referendum on the constitution of the country. This is our main challenge right now.”

In an increasingly optimistic tone, Mohsen concluded:

“I can say that Iran is the only country in the whole region that, if we can have a free and fair election, that definitely seculars will win. And I believe that if we can have a referendum on the constitution, definitely the majority of the people—the absolute majority—will say NO to this constitution and will go for a democratic secular regime.”

Sazegara sees widespread, strategic, disciplined civil resistance as a key factor in driving such a change. Realizing his strategic vantage point as a diaspora hell-raiser, the primary aim of Sazegara’s daily activities is to equip his fellow citizens with the tools and knowledge they need to succeed.

SaveSave

Amber French

Amber French is Senior Editorial Advisor at ICNC, Managing Editor of the Minds of the Movement blog (est. June 2017) and Project Co-Lead of REACT (Research-in-Action) focusing on the power of activist writing. Currently based in Paris, France, she continues to develop thought leadership on civil resistance in French.

Read More