Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Merab IngabireFebruary 18, 2025

As an African living in a country where activist writing is criminalized, using words as a form of resistance is both dangerous and revolutionary. Writing as an activist in my context is fraught with peril because words can expose injustices, challenge the status quo, and hold those in power accountable. These are precisely the reasons why oppressive regimes fear and suppress them. In my country, Uganda, critical writing is often equated with sedition or incitement to violence. Laws such as the Computer Misuse Act are weaponized to silence dissenting voices, with writers and artists accused of threatening national security or undermining public order.

Thousands of communities around Uganda continue to suffer because of land grabbing. Much of my writing has focused on building power for communities impacted by this unjust practice. Credit: Solidarity Uganda.

Writing is dangerous in repressive environments. The danger lies not only in state censorship but in the broader societal consequences. As an activist and writer who uses storytelling as a revolutionary tool, I’ve faced much criticism, even from activist circles. Some label us cowards, frauds, or too safe, claiming that real resistance happens only in the streets. But how can they ignore the countless comrades who have been arrested, tortured, or disappeared because of their writing? How can anyone call this form of resistance cowardly when so many have been forced into exile, torn away from their motherlands and loved ones for daring to speak truth to power?

I once published an article about a land grabbing scandal involving an army general. When the article went live, I received numerous calls from close family members and friends asking if I was tired of living. They questioned why I was targeting influential people, unafraid of silencing anyone or anything threatening their power. Some even called me selfish, claiming I was risking their lives and oblivious to how my activism was affecting them. Although I was disappointed and hurt by some of their comments, I understood their fears because I have witnessed firsthand how the oppressive regime harasses activists and their families. When they cannot directly reach you, they go after your loved ones, using them to isolate and control you without ever locking you up.

The fear and uncertainty of activism are palpable, as you never know when the regime will strike next. The consequences of this are dire, and they psychologically torture you by making you think and feel alone. Your family and friends shun you because they fear their association with you puts them at risk. You become lonely, and this isolation can be very dangerous as it takes you to dark places. You wonder whether it is worth it. The personal sacrifices made in the fight against oppression are immense, as you find yourself standing alone against a ruthless system. The very people who should stand with you are forced to stand against you.

Confronted with these difficulties, it is only very recently that I have begun focusing on my mental health. I met Rosie Motene, a life coach, activist and feminist who provided daily reflection and yoga sessions at a summit of activist-creatives I attended recently in East Africa. Making time for these practices, even if that means just a few minutes a day, may not seem essential, but they have had a significant positive impact on my mental health.

Navigating repressive environments

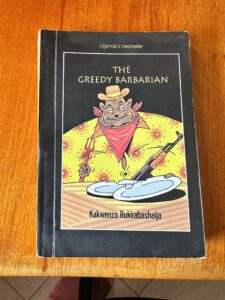

Kakwenza Rukirabashaija's book, The Greedy Barbarian.

Despite these obstacles, writers and artists in oppressive settings persevere. One of the most effective strategies in activist writing is the use of humor, symbolism and metaphor. Activists often mask their critiques in satire employing artistic ambiguity to speak truth to power. For example, fiction can become a subtle yet sharp tool for critiquing political corruption, using invented worlds or characters to reflect harsh realities like exiled activist Kakwenza Rukirabasaija does. These creative approaches not only make it harder for regimes to directly censor or penalize them but also allow their messages to resonate deeply with audiences. Symbolism becomes a shield and a weapon, a way to challenge oppression without exposing oneself entirely to its full force.

My articles have been altered, stripped of important details, or outright rejected. Editors often admit their hands are tied, confessing that while the articles are powerful and necessary, publishing them would endanger their own safety. With local and national media often stifled by state control or media house self-censorship, many activist writers are forced to turn to online spaces and global collaborations to amplify their struggles. These international collaborations allow them to share their stories with not just the local audience but the global audience as well. This kind of visibility has proven strategic and essential for protecting activists. It adds a layer of security in the form of international attention, which can deter some dangerous state actions.

The emotional toll

Many fail to acknowledge the immense emotional toll of using words to resist. Writing under constant threat demands a level of vulnerability that is often underestimated. Every sentence written is a confrontation with fear, and every piece published is a leap of faith into uncertainty. Activists who write as a form of resistance carry the emotional weight of their words, fear for their safety, the guilt of putting loved ones at risk, and the heartbreak of being misunderstood even within their movements.

It’s easy to focus on the power of writing without recognizing its cost. Yet, understanding and embracing this emotional toll is critical. We must allow ourselves to deeply feel the pain, fear, and exhaustion because it is through this vulnerability that our work remains authentic and impactful. It's important to acknowledge the emotional burden of activism, as it validates our experiences as activist writers and fosters empathy and understanding among readers. Activists who ignore this toll risk burnout, disconnection, and a loss of purpose.

As activist writers, we must acknowledge the emotional burdens of our resistance. We must create networks and safe spaces, formal or underground, to share our work and offer emotional support and solidarity. We can find strength in community and self-compassion. Writing reminds us that courage is not the absence of fear but the persistence to act despite it. Writing is not just about the fight but also about healing, solidarity, and profound hope for a better future.

Merab Ingabire

Based in Kampala, Merab Ingabire is a member of the leadership team and head of advocacy and communications at Solidarity Uganda. She is also a prolific photojournalist and writer/documenter of civil resistance movements.

Read More