Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Inna Kavalionak and Ala SivetsJune 30, 2021

Political prisoners are often invisible. By facilitating and amplifying small acts of solidarity, the user-generated content website Politzek.me makes political prisoners in Belarus more visible—and advances the country's nonviolent struggle for democracy. Here’s how.

Belarus’s struggle for democracy began in August 2020 and repression has only intensified in recent months. People have been arrested even just for wearing white-red-white socks (symbolic colors adopted by the movement), and criminal prosecution of activists is common. The country counts at least 520 political prisoners at the moment, which would proportionally equal 16,500 people in the United States. Close to 3,000 criminal cases have been initiated for political reasons since the beginning of the political crisis since last summer. Many of the individuals involved are believed to be in detention centers right now.

However, strong solidarity and will to make change through nonviolent action are countering these forces. Both in the detention centers and outside, Belarusian people live under constant pressure and need to be supported. This was the main reason we created the Politzek.me project.

What is Politzek.me? Our objectives are to channel support for political prisoners and their relatives, and to raise international awareness of the human rights violations that are happening in Belarus right now. For this, we work extensively with NGOs, the media and politicians. But we also encourage ordinary people to help the Belarusian prisoners in concrete ways. Simple and strategic actions by people in society can make a big difference.

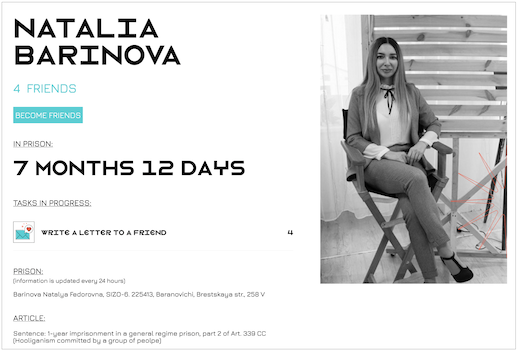

The Politzek.me profile of Natalia Barinova, political prisoner in Belarus' pro-democracy struggle.

Therefore, we created a tool to encourage and sustain solidarity. On our website you can “friend” a political prisoner, just as you would on social media (but without direct contact with the person), and start supporting them with simple actions.

To become a friend, a user first commits to completing at least one act of solidarity for their future friend. When clicking on “become friends”, a list of possible actions is displayed. The tasks range from simply sharing the prisoner’s story on your social media channels, to more complex ones such as sending a package with supplies to the prisoner. We suggest a wide variety of actions to make the support feasible and to ensure long-term involvement. If a person isn’t up for completing a major action this week, they can complete a small solidarity gesture and come back later to the other actions. Thus, the acts of support and solidarity are uninterrupted, and we draw people back to the site by periodically promoting new actions.

We have good user retention, because all the information users need is in one place and they can easily track their progress on our site. For example, users have their own profiles where they can see their “friends” and the actions they’ve completed.

Student political prisoners receiving support via Politzek.me. Source: Politzek's Facebook page.

When a user completes an act of solidarity, it is displayed on the prisoner’s profile too. This way, everyone can see what is being done for the political prisoner and how many friends he or she has. This also makes it easy to see which political prisoners need more support.

Prisoner profiles also detail their detention background, the charges that were brought against them, and other information about them. Prisoners often write response letters to their “friends”, but of course, the prisoners cannot reply online. Friends of prisoners can boast about a job well done once they complete a task for their “friend”, and it will be displayed on the prisoner’s profile.

Source: Politzek.me's Facebook page.

So this is a user-generated content (UGC) website, which makes for a very dynamic experience. We are bridging the gap between the online and offline worlds, which is such a challenge for online activism in general.

Above all, our approach fits our main intention: We want to turn the political prisoners into superstars. They are ordinary people who stood up for our collective freedom, and now they are suffering. So yes, they are stars—our superstars for justice and democracy. This approach is what drove our site design and general attitude.

Politzek.me users sometimes gather to write letters to political prisoners. Source: Politzek.me's Facebook page.

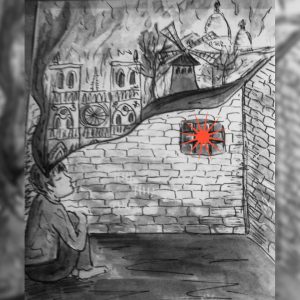

We launched the project in December 2020, though the idea emerged in September of that year (implementation was slow, as we all are working as volunteers). The most popular action is sending letters of support to political prisoners. People even like to gather offline to write letters. We have record of over 9,000 letters sent, plus another 3,000 postcards or drawings. Another popular action is wearing black on Fridays, which has been documented by some 900 users. Less often, people attend court hearings (212 instances) or mail packages (211 instances). As of now, political prisoners have a total of 13,171 friends and 18,333 actions have been completed.

However, tracking this progress is a challenge. In order to submit a completed action, a user must log into the site. Yet many people in Belarus are afraid of leaving behind electronic evidence of their participation in the pro-democracy struggle. We know that far more people are writing letters and completing tasks, because we receive feedback in-person.

Politzek.me users have sent some 3,000 postcards and drawings to political prisoners in Belarus. Source: Politzek.me's Instagram website.

The Politzek.me project is growing. We are working tirelessly to engage more people, and for this purpose we launched a prisoners’ map on our website so that users can locate prisoners nearby. We also publish guides and news items. Further, we plan to integrate calendars so that users may turn on notifications to complete actions.

In the face of violence, visible acts of solidarity are what changes society at its core. And right now, we should help the Belarusian people. Each day as we wake up and get dressed, Belarusian political prisoners are experiencing trauma in the name of their—our—freedom. To support them and the movement, major sacrifice on our part isn’t even necessary. This is where crowdsourcing solidarity comes in. Small actions by each of us as a group lead to major impact.

Ready to join? Subscribe to our social media channels, visit the webpage Politzek.me (in Russian and English) and:

- Share political prisoners’ stories (media censorship in Belarus means all of us must act as the media);

- Send a letter to a political prisoner (follow the guide here);

- Get involved with your local Belarusian diaspora (for example in Norway and Germany).

We are stronger as friends. Together we win!

Inna Kavalionak

Until May 2020, Inna Kavalionak was a theater producer working at the OK16 cultural hub in Minsk, Belarus. Then she began volunteering for the election campaign of opposition candidate and philanthropist Viktor Babariko. She was soon arrested for her pro-democracy activism surrounding the contested 2020 elections. Since December 2020, Inna has been heading up politzek.me, an activist-run, user content generated website that channels online and offline support for political prisoners in Belarus.

Read MoreAla Sivets

Ala Sivets is a researcher and human rights activist. She holds an MA in Euroculture from Uppsala University and the University of Udine with a focus on European Union politics and human rights. Her research interests are forced migration and integration, mental well-being, diversity and community building. Observing numerous detentions of her friends in Belarus, Ala joined Politzek.me in 2020 as an advocacy campaigner.

Read More