Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Sara Vazquez MelendezJuly 25, 2019

For the past 40 years, the community of Tallaboa Encarnación, in the municipality of Peñuelas, Puerto Rico, has been the site of sustained civil resistance campaigns against environmental polluters in the area. Yet the struggle has intensified in the past few months.

Last May, Peñuelas residents met in front of the nearby Applied Energy Services (AES) coal-fired power plant to demand that this multinational corporation close down its operations in Puerto Rico. The Peñuelas community demands have included removal of the mountain of coal ashes on the AES premises, and monitoring and cleaning of areas where ashes have been deposited. The ashes, which are produced by coal combustion for electricity generation, contain arsenic and mercury, among other toxic metals.

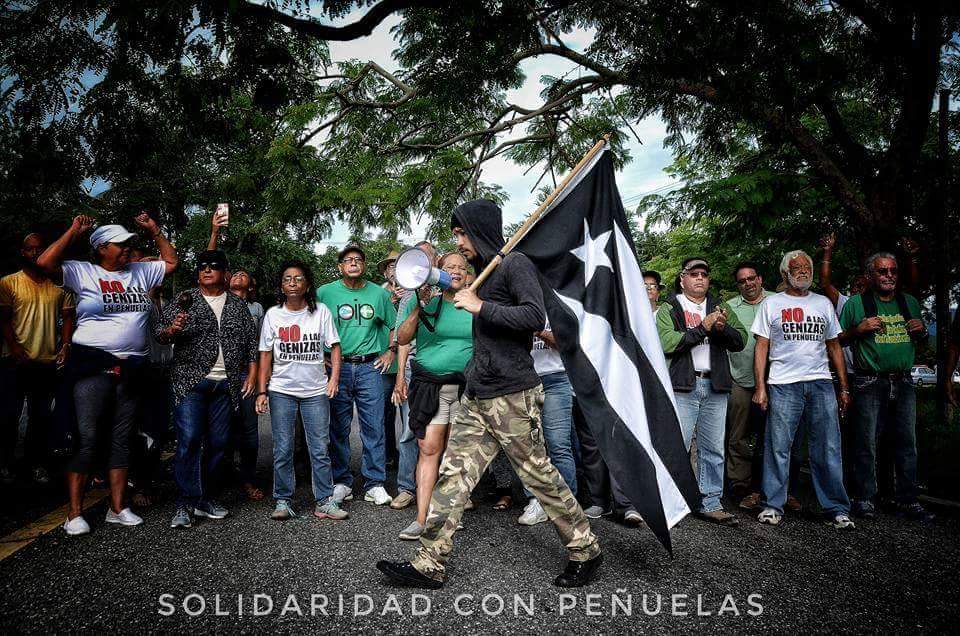

The picket line leading to the AES entrance was met by a line of police and private security, whose excessive use of force against peaceful protesters received national attention. People from all over the island arrived at the landfill entrance to join the nonviolent occupation.

Despite—or rather owing to—the government repression, the action even received support from various unions, religious organizations, and the Puerto Rican diaspora, including letters of support from the community in Colombia, the origin country of the coal in Puerto Rico.

The struggle—which has now grown from local to transnational—is about much more than environmental concerns. It’s also about decolonization of a US colony whose inhabitants lack the political freedom to determine their own future—and who have seen exploitative foreign and multinational corporations (MNCs) engage in abusive practices for the past seven decades. MNCs have the Puerto Rican government in their pocket which, as you’ll read below, doesn’t often translate to respect for residents’ livelihoods.

Civil resistance in parallel with other actions

The community uses civil resistance in parallel with institutional means of struggle—namely awareness-raising and legal actions. For example, on June 24, 2014, Peñuelas residents organized a permanent camp at the entrance of their town, where educational and cultural activities were and still are held to raise consciousness among locals and visitors about the environmental dangers of coal ashes. In addition, later that year, Peñuelas passed an ordinance declaring illegal the deposit of coal ashes in its jurisdiction.

But the Puerto Rican government, which condones and even materially supports the deposit of coal ashes in Peñuelas, has repeatedly broken the ordinance. In 2015, the original contract with AES was amended to allow for the coal ash deposits in Puerto Rico. The government claims that the ashes can be used in the construction of roads and houses.

In 2017, the government of Puerto Rico passed Law 40 which permits coal ash deposits in landfills and other places in Puerto Rico. For AES, depositing the coal ashes in Puerto Rico is cheaper than exporting them. However, due to the civil resistance campaign taking place in Peñuelas, the AES has been forced to take the ashes out of Puerto Rico.

Because these institutional channels of struggle were for a long time insufficient on their own, residents began leveraging pressure on AES and the government through people power to put an end to the environmental injustices happening in Peñuelas.

Origins of the struggle, and challenges

The Peñuelas struggle against the deposit of toxic industrial waste first began in the 1960s and 70s, when a petrochemical plant first opened its doors at the entrance to the town. The industrial waste produced in this plant was dumped in an illegal landfill. When the community began to voice its concern about the environmental impact of this practice, the owners of the landfill, with the help of the local government, began expediting the permits for the landfill.

This same landfill is the one that has now received over 300 tons of coal ashes within the past few years. One of the challenges that the community encountered early on was selecting appropriate nonviolent actions and building community participation in the resistance.

Diversifying tactics and methods of struggle

With 40 years of experience in civil resistance under their belt, community activists have learned the importance of diversifying their nonviolent tactics. In my interview with community leader Jose Manuel Diaz Perez, he explained that they have moved away from what he considers “just using protest to voice their discomfort” to working with members of the scientific community and other groups to gather scientific information on the toxicity of the waste. Then they present this knowledge to the community. This had a direct positive result in the level of participation in civil resistance campaigns—and has reinforced the community’s commitment to mixing information dissemination actions with civil resistance.

As Perez puts it, the lack of political power of Puerto Rico and its colonial relationship with the United States is one of the major forces driving environmental pollution. The central government of Puerto Rico is often aligned with the interests of foreign and multinational corporations, whose interests are protected to the detriment of Puerto Ricans’ well-being.

Victories, big and small, yet the struggle continues

The community’s persistence over the years has brought about a number of victories. First, in response to the civil resistance campaign taking place in Peñuelas forced AES to take the ashes out of Puerto Rico, as it was stipulated in the original 1994 contract. This is even despite the 2017 law according to which AES is allowed to deposit the coal ashes on the island. In April this year, the Puerto Rican government announced that the coal plant in Guayama, Puerto Rico, would be closed by 2020.

Whether or not this announcement was simply made to appease protesters ahead of the 2020 elections for governor of Puerto Rico, the effectiveness of the camp against the deposit of coal ashes in Peñuelas cannot be denied. One indication of this was a report released last March, in which AES finally admitted to having contaminated an aquifer near its coal plant.

However, while the problem has subsided for Peñuelas residents, it has by no means disappeared: AES is now exporting the ashes to a landfill in Osceola, Florida, USA, where coincidently, a community of Puerto Rican diaspora lives.

The struggle for decolonization and environmental justice continues in Peñuelas and the rest of Puerto Rico. But in absolute terms, people power among Puerto Ricans—not as an isolated community, but instead one supported by others across the country and in other parts of the world—has induced corporate and government actions in favor of environmental justice.

The diaspora is taking its cue from the Peñuelas community and is fighting for environmental justice. From the dissemination of information regarding the toxicity of the coal ashes, to forming alliances with environmental justice organizations, and working with the Puerto Rican communities that are fighting to close the coal power plant; the diaspora is creating a diverse, international coalition to pressure the Puerto Rican government to move away from the production of energy by toxic means and toward renewable sources of energy production.

The author may be contacted at: escuelaresistencia@hotmail.com.

Sara Vazquez Melendez

Sara Vazquez Melendez is an anthropologist, farmer, activist and educator in Ponce, Puerto Rico. Through her school in civil resistance, and her agroecology farm, she provides a framework for decolonization, as well as methods for building an alternative future.

Read More