Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Phil WilmotAugust 16, 2022

In March 2019, following numerous community pleas to curb graft among local police that had fallen upon deaf ears, residents of Kyere, Uganda tricked a notoriously corrupt police officer into a bribery arrangement. They caught him red-handed. Emerging from their hiding places in a community market, they seized the officer and arrested him—a man who had often used the same power of arrest to extort from them! This effective sting operation occurred without any of the usual police brutality toward activists.

As democracy erodes at an increasing pace, slipping our species toward the normalization of authoritarianism, protesters are understandably exploring how they can stay safe.

But reducing the risks of our nonviolent actions can also come at a cost—the cost of our power. It is often believed to be safer to get off the streets and onto social media, but not only has this logic been proven false, social media impact is also questionable. Regardless, even though it is usually safe to lobby our leaders, many of them won't budge an inch until they face a powerful popular movement with clear demands.

Recognizing the stakes and the urgency of the moment, there are many activists quite ready to take greater risks. It would make sense, then, for them to engage in courageous acts when the potential reward of their action outweighs the repression they could face. They should be as sure as they can that their efforts will be worth the worst consequences imagined.

A palate for risk

Click to enlarge. Image held in Creative Commons and can be used or edited for any purpose without attribution.

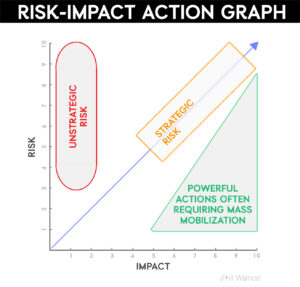

To determine whether a particular tactic's potential payoff is worth the risk, I grabbed inspiration from existing risk assessment tools (Ivan Marovic’s cost/benefit analysis, the Curle Diagram, etc.) to develop the Risk-Impact Action Graph, a graph tool that activist teams can use to more precisely discern which risks are strategic to incur, and which aren't worth the trouble.

I was motivated to create a new tool that helps navigate this risk-reward question after witnessing pro-democracy activists in Uganda brutalized by armed state actors over and over again. Activist and regime tactics were repetitive, producing fairly consistent outcomes. Marches, placard-holding, and the usual public demonstrations would be met with violent repression and then dispersed by the state. A handful of die-hards would be arrested. The protests—courageous and important as they were—wouldn't usually move the needle noticeably.

Yet many activists were willing to be arrested. Several were recurring detainees. With this developed palate for risk, they could be taking even more powerful actions beyond their usual symbolic and persuasive protests.

Some activists in Uganda caught on to this in recent years, and a culture of direct action continues to grow there. Instead of merely advocating for uncooperative political leaders to yield to community pleas, youth started blockading business vehicles, occupying strategic offices, and carrying out citizen's arrests, like the one mentioned above. These high-stakes actions rarely led to the brutalization or arrest of activists. Conversely, the results in terms of reclaiming land and public funds, for instance, were in many cases extraordinary.

By taking greater risks, they were gaining greater rewards! That being said, there are some nuances to unpack, and I turn to this further below. First, how do activists use the Risk-Impact Action Graph?

How to use the Risk-Impact Action Graph

Citizens in Uganda arrest a politician for abuse of office, abetting criminal cases, extortion, and more. August 2019. Credit: Solidarity Uganda.

In mathematical terms, the relationship between risk and impact is linear. A rather safe action like distributing a leaflet is likely not to gain much momentum for activists, but if they up the ante and carry out an illegal and dramatic search and seizure, for instance, this could produce tremendous gains for their movement.

Brilliant, or terrible, tactical strategizing occurs in the outliers. When activists create a low-risk tactic that yields powerful results, they've discovered something that can really advance their campaign objectives and broaden participation. Conversely, if they carry out lots of high-risk, low-reward actions, they discourage newcomers and would-be recruits.

To determine where a tactic falls on the graph, score its risk level from 0 to 10. Then score its probable outcome from 0 to 10. If your rankings are two figures away or less (e.g. 7 and 8), you have a tactic worth considering. Refine the tactic a bit to reduce the risks by preparing for them, and by using the Action Star to plan more thoroughly for better results. If you’re not sure whether to go ahead with a particular tactic, you can “break the tie” by comparing it with other actions that have taken place in political conditions similar to yours (for example by conducting research via the Global Nonviolent Action Database of over 1,200 campaigns, or on ICNC’s website and this blog). If you expect to face repression, you can also begin strategizing on making the repression backfire.

Hybridizing tactics for optimal results

You can also call a creative brainstorming session with a small number of experienced activists to discuss how to hybridize the tactic. This means that if the tactic is dispersed, you would brainstorm how it might take on more characteristics of a concentrated tactic, and vice versa.

One example is Europe Must Act’s “peopleless” campaign for refugee rights. Where a demonstration would have physically brought together hundreds or thousands of people, organizers instead encouraged people to visit the demonstration location in a dispersed manner and leave protest signs or other objects. A video was later mass-disseminated documenting all the visits and contributions to the demonstration. Thus, the demonstration optimized the benefits of a concentrated tactic (mass participation) while also maximizing the benefits of a dispersed tactic (lesser risk of a crackdown).

If the potential impact of the tactic is far higher than the risk, consider whether you have what it takes to make it happen. Many low-risk, high-reward tactics, such as a mass consumer boycott and a stay-home strike, are powerful because they involve mass participation. However, mass participation isn't born overnight and often requires a strong network of persistent community organizers. It may also need to be preceded by certain high-risk actions to gain attention and galvanize public support. For example, the dramatic and high-risk 1960 Nashville lunch counter sit-ins during the US Civil Rights Movement led to a broader community boycott of downtown Nashville businesses.

Know your movement, know your risk

What it comes down to is this: We should do low-risk, high-reward actions if we have the resources and infrastructure for them. In many cases, it is mass participation which actually makes them low-risk, high-reward (“power in numbers”). If they are done without mass participation, then they will fall into one of two categories: 1) low-risk, low-reward, which can still be appropriate in many struggles as participation begins to grow, or 2) high-risk, low-reward, and therefore should be avoided.

If you use this Risk-Impact Action Graph, I'd love to know what thoughts you have about it. Email me with your experience and let’s chat (my email address is on my contributor page below).

By learning together we can take more calculated risks together too.

Phil Wilmot

Phil Wilmot is a former ICNC Learning Initiatives Network Fellow, co-founder of Solidarity Uganda, and a member of the Global Social Movement Centre and Beautiful Trouble. Phil writes extensively on resistance movements and resides in East Africa. Write to Phil at phil@beautifultrouble.org.

Read More