Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Hardy MerrimanNovember 21, 2019

A wave of largely nonviolent uprisings in 2019 has led to a profusion of media articles on this topic, examining questions such as: Why are so many people protesting now? Is this part of a larger trend? Are common issues driving these uprisings? Where will these uprisings lead?

It’s hard to address these in soundbite form. The international landscape is complicated, and the differences between the many uprisings this year are just as interesting as their commonalities. Here are some thoughts.

Why are people protesting in so many places?

There are always local factors, and the first thing we have to do is listen to those who are mobilizing. People in Hong Kong, Indonesia, West Papua, Sudan, Algeria, Guinea, Catalonia, Russia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Lebanon, Iraq, Iran, Pakistan, Chile, Ecuador, Nicaragua, Venezuela, Bolivia, Haiti, the United States, and many other countries—as well as worldwide (i.e. Climate Strikes)—have all engaged in public demonstrations this year. In each case, people have their own grievances and aspirations, which overlap in some instances, and in others do not.

Chileans protest in Plaza Baquedano, October 2019. Source: Wikimedia

Certain kinds of immediate grievances (sometimes called “trigger events”) may be more likely to foster collective action. For example, a tax on the use of WhatsApp (as in Lebanon), or an increase in subway fares (as in Chile), or an increase in fuel prices (as in Iran) create a common experience that is shared by a large and diverse range of people. This shared experience, and the anger that it produces, can facilitate collective action and mobilization by groups that otherwise might not work together.

Other trigger events can build hope and confidence, which can also lead to collective action. For example, a popular nonviolent uprising that is achieving political change in a nearby province or country can sometimes have a contagion effect. If people perceive an opportunity for change, that can drive them to mobilize. This could be a catalyst for the current spread of demonstrations in Latin America or the Middle East.

Beyond trigger events, popular mobilization is also driven by deep emotion, which may come from years of accumulated grievances and aspirations for change. People often report feeling that their dignity is insulted, and conclude that if they don't draw a line and set limits with powerholders, then they will continue to suffer exploitation and abuse. As one local commentator of the Lebanese uprising stated:

Demonstrations in Lebanon, October 2019. Source: Wikimedia

If you wanted to give this a name, it would be the ‘uprising of dignity’—people taking back their dignity because it’s so humiliating to be a citizen of Lebanon under this ruling class. You know that the country can be doing much better than this, you know you’re not responsible for how bad the situation is, and yet these people just keep on dividing us and taking actions against our interests.

But even strong emotions and a trigger event are generally not enough. Collective action does not happen automatically based on some formulaic set of static or changing circumstances. There are hundreds of bad policies and bad decisions by governments around the world every day that don't trigger collective action. When people are angry they may stay home because they feel confused about what to do, or distrust their neighbors, or feel powerless and hopeless.

What transforms deep emotions and a trigger event into action is often the presence of grassroots activists and organizers. In many cases these individuals have prepared ahead of time to mobilize, built trust and confidence among different groups, and developed skills at unifying people and organizing protests, strikes, boycotts, and other nonviolent actions. People with these skills and experience are incredibly important in times like these by helping to shape the direction of popular mobilization. When others are confused about what to do, activists and organizers (most of whom are not high-profile leaders) can provide guidance.

What transforms deep emotions and a trigger event into action is often the presence of grassroots activists and organizers. In many cases these individuals have prepared ahead of time to mobilize, built trust and confidence among different groups, and developed skills at unifying people and organizing protests, strikes, boycotts, and other nonviolent actions. People with these skills and experience are incredibly important in times like these by helping to shape the direction of popular mobilization. When others are confused about what to do, activists and organizers (most of whom are not high-profile leaders) can provide guidance.

In my view, activists and organizers frequently don't get enough credit for their important role in developing and guiding popular mobilization. Incidentally, they also sometimes create their own trigger events. To take a classic example, Rosa Parks' pre-planned refusal to give up her bus seat to a white passenger was a trigger for the 1955 Montgomery bus boycotts.

There are many other individual and political, material, and social factors (e.g. friends often recruit other friends to mobilize) that can influence collective action, so the above list is not meant to be exhaustive. While it is often easiest to point out trigger events and deeply felt grievances, discerning the role of activists takes more time and work to research from the outside. However, understanding this role is essential, since deliberate choices, strategies, and skills matter in the process of mobilization, and certainly the sustainability and outcomes of mobilization.

Algerians demonstrate against a fifth term of President Bouteflika (Blida), March 10, 2019. Source: Wikimedia

Is there a global trend towards increasing protest?

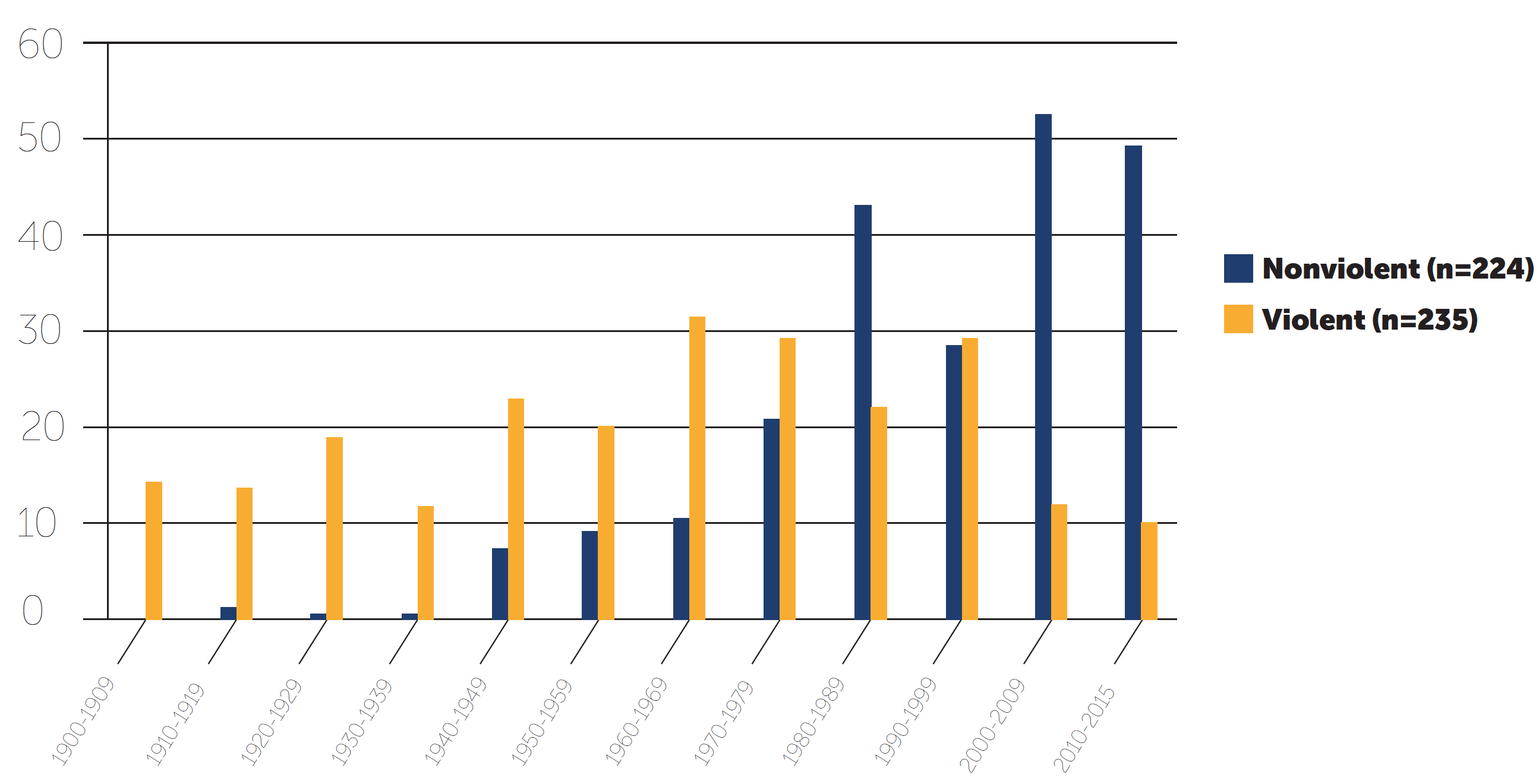

Recent protests reflect a growing trend of new civil resistance movements that goes back almost 30 years. Harvard University professor Erica Chenoweth has documented this. The number of new civil resistance movements trying to achieve political transitions or other “maximalist” changes (such as self-determination or expelling a foreign occupier) nearly doubled from the decade of 1990-1999 to the decade of 2000-2009. And between 2010-2015, there were nearly as many new movements as there were in the entire previous decade of 2000-2009.

Onset of Movements Seeking Political Transition,

Self-determination, or an End to Foreign Occupation: 1900-2015

Source: Major Episodes of Contention data set, as cited here.

Notably, these findings do not include campaigns for social, economic, or policy change (other than a change of government). Were these to be counted as well, I suspect we would see a big increase in local and regional labor struggles; grassroots anti-corruption campaigns; struggles for women’s rights, minority rights, indigenous rights, environmental justice, peace and security; and a variety of goals around the world. These campaigns sometimes feed into (or transform into) national level movements for political transitions, so if we’re seeing more of the latter, we’re also likely to see many more of the former.

This leads to a couple important clarifications about definitions. Most media are covering protests, but the above points relate to civil resistance. Civil resistance is a way of fighting that includes a wide range of nonviolent tactics such as mass demonstrations, strikes, boycotts, civil disobedience, and many of other acts of noncooperation. Therefore, protest is an act of civil resistance, but not all civil resistance takes the form of protest. To win significant change, people often have to move beyond protest and engage in other civil resistance tactics.

Secondly, the above points refer to movements. A movement involves widespread voluntary participation that persists over time, but a protest can simply be a spontaneous act that rapidly declines with no follow up. Many movements engage in protest, but not all protests indicate the presence of a movement. Since change takes time, movements are often essential to achieve it.

These distinctions are important when we consider what the meaning and likely outcomes of these protests will be. A protest by itself may not be evidence of much more than pent up frustration. A civil resistance movement that organizes a protest—or a protest that starts the development of a civil resistance movement—is going to have a longer trajectory and greater impact. At a given moment in time, various protests and the circumstances around them may look similar, but the structure, strategy, and basis of unity that underlies them is often what makes them different.

In July and August 2019, Puerto Ricans mobilized to push for accountable government and decolonization. Source: La Colectiva Feminista.

Are there common issues or factors that unite the recent wave of protests?

There are a range of issues, groups, and goals driving protests in various countries. Some people demand democracy. Some want an end to repression. Some people live in a democracy but experience increasing economic hardship and unaccountable governance. Some seek human rights or environmental justice. Some seek greater autonomy and self-determination.

There can also be a generational element to uprisings. Young people are often critical in movements for change. In some places, such as Chile, the value of retirees' pensions is diminishing which may drive mobilization by older generations. In some places women, or people in certain vocations, or members of minority populations may be more likely to mobilize because they are highly impacted by certain forms of societal oppression, and/or have the most experience with community organizing and civil resistance from past campaigns.

With so many populations in different countries currently demanding change, diversity is a hallmark of this wave of uprisings.

There are some commonalities as well. A backdrop for all of them is the very troubling global trend of backsliding democracy and rising authoritarianism around the world. The organization Freedom House ranks every country and territory in the world on political rights and civil liberties each year and shows that worldwide, democracy has declined for 13 consecutive years. This means that there are more authoritarian governments in the world now than a decade ago, and that many democracies themselves are eroding.

When governments become more authoritarian, they become less accountable and are likely to become more corrupt and abusive. The wave of current uprisings shows that many people have concluded that the traditional institutional means of making change—elections, the legal system, and dialogue with elites—by themselves are insufficient to address their concerns and make the changes they want to see. For example, a corrupt executive and legislature creates corrupt elections, and a corrupt judiciary cannot or will not constrain them.

When governments become more authoritarian, they become less accountable and are likely to become more corrupt and abusive. The wave of current uprisings shows that many people have concluded that the traditional institutional means of making change—elections, the legal system, and dialogue with elites—by themselves are insufficient to address their concerns and make the changes they want to see. For example, a corrupt executive and legislature creates corrupt elections, and a corrupt judiciary cannot or will not constrain them.

As a result, protesters are looking for another form of power to force constructive change to happen. This does not mean that people have given up entirely on institutional means of change. Sometimes it means that they use civil resistance to try to get institutional means to work again. Sometimes civil resistance is needed to revitalize democratic processes.

Another common element in the current wave of uprisings is that most of the people who are mobilizing are choosing nonviolent methods instead of violent methods. If this choice is maintained, significant research tells us that they will be much more likely to achieve their goals over time than if they lapse into violence.

Protests in Jakarta, Indonesia, September 2019. Source: Wikimedia

Where are these uprisings going to lead?

Considering local social, political, and economic circumstances are important, but they do not tell us the whole story. Multiple research studies (here, here, and here) show that structural conditions can influence a movement, but they alone do not determine a movement’s trajectory and outcome. Factors that are much more within a movement’s control—such as its choices, strategies, and skills—are highly significant in enabling a movement to transform or overcome adverse circumstances and win. For example, earlier this year, a highly diverse movement (in which women were key organizers and leaders) in Sudan ended the rule of 30-year dictator Omar al-Bashir. Structural conditions in Sudan (regime brutality and ethnic factionalization, among others) were very challenging, but through strategy, skill, and persistence, the movement was able to maneuver to victory.

Therefore, if we want to know where the current wave of protests are going, we can ask some key analytical questions that relate to the skills and choices of the civil resisters. These questions are relevant whether we’re a journalist trying to analyze recent protests, or an individual actively organizing in solidarity or within them:

Unity:

• Are participants united around clear goals, means (nonviolent, institutional, or violent), and basic strategy (particularly sequencing of priorities) to achieve these goals?

• Are there clear values and principles of decision-making and action that everyone in the movement shares? Better yet, is there a process of training or orienting new supporters that conveys these values and a common framework for understanding how the movement will make change?

• Are participants actively reaching out to new demographic groups and building networks of trust and solidarity?

• If there are clear public leaders of the movement, are they united with the grassroots?

Strategy:

• Are participants making use of an expanding range of civil resistance tactics (such as strikes, boycotts and a variety of high- or low-risk acts of noncooperation) that enable a growing number of people to participate, and create a range of pressures? Or are participants stuck in cycles of protest?

• Are tactics being sequenced in a way that exploits the movement’s opponent’s weaknesses and escalates pressure?

• Are participants able to prepare and plan, mobilize to advance their goals, and pull back and reassess as needed? Or are they trying constantly to mobilize publicly, which can lead to exhaustion and burnout?

• Are participants building a program or process of training current and new supporters?

• Is there acceptance of the need for a multi-year strategy? Or do people appear confused and lose confidence if they have not achieved all their goals in a short-time frame?

(Note: Research tells us that the average nonviolent campaign takes three years to conclude. Sometimes a movement is making strong progress but has unrealistic expectations about timeframes. Participants can then mistakenly become convinced that they are losing when they have not achieved all their goals in a few months, and this can cause them to start acting in un-strategic ways, for example by using violence.)

Nonviolent Discipline:

• Are participants firmly committed to nonviolent tactics?

• Is nonviolent discipline stressed in public statements, actions, and trainings?

• Do participants pledge or have a code of conduct that requires remaining nonviolent at public actions?

• Do participants agree about whether property destruction is permissible or not?

• Are there low-risk nonviolent tactics (i.e. consumer boycotts) that people can get involved in that reduce or eliminate the risk that they will be targeted with repression or lose nonviolent discipline?

These qualities of unity, strategy, and nonviolent discipline are some of the most important attributes in successful movements (as I’ve written about here, and in more depth here). Together, they foster widespread public participation (which creates power), cause repression to backfire (which weakens the movement’s adversary), and ultimately lead to defections by their opponent's supporters (which forces the opponent to make concessions).

Recognizing the complexities of real-world organizing, operating environments, and timeframes, it’s rare to find a movement that perfectly embodies every ideal of effective organizing. Activists have one of the toughest and most important jobs in the world, and movements do not need perfect unity or strategy to succeed. Some movements even succeed in spite of the presence of violent flanks.

Recognizing the complexities of real-world organizing, operating environments, and timeframes, it’s rare to find a movement that perfectly embodies every ideal of effective organizing. Activists have one of the toughest and most important jobs in the world, and movements do not need perfect unity or strategy to succeed. Some movements even succeed in spite of the presence of violent flanks.

That said, in challenging circumstances, the demands required for success are often very high. People have met those heights in the past, and they provide guidance for the future.

So as the current wave of uprisings continue, much will depend on the decisions of people on the ground who are mobilizing. Greater variations in different locations will emerge over time. Some protests that we see currently are organized by long-established movements that will likely continue. Others may lead to new movements. Others may never become movements and rapidly decline. Some cases will yield gains quickly and others will have indeterminate outcomes for a period of time (which is not always a bad thing—a longer fight may result in a deeper transformation and more resilient victory). Some may collapse under a regime crackdown, while others may persist in spite of violent repression. Some are moving toward using violent tactics themselves, which portends really tough days ahead. Others may respond to repression by remaining nonviolent and innovating tactically (i.e. changing from protests to a general strike or boycotts, which are harder to repress). Some will build structures that help them function but remain sufficiently fluid to generate continued popular mobilization. Others may remain too unstructured to sustain unity around clear goals and strategies, or become so structured that they become formalized in the world of political parties and NGOs.

We can also be certain that as these movements continue, violent repression will cause some to question commitment to nonviolent means. For example in Hong Kong, this slogan has been expressed to the authorities and police since at least July 2019:

“It was you who taught me that peaceful marches are useless.” Source: @jeffielam (photo by Martin Lam).

“It was you who taught me that peaceful marches are useless.”

While people’s anger is understandable, the research on this point is clear. Civil resistance is about far more than peaceful marches, and the idea that extensive property destruction or violence will be more effective than civil resistance is strongly contradicted by a growing body of evidence. Extensive historical data tells us that on average, civil resistance movements have been twice as effective at achieving their stated goals as violent uprisings. Violent uprisings also tend to lead to more violence by a movement's opponent. For example, violent movements seeking political transitions or other maximalist objectives result in mass killings (defined as 1,000 civilians in a single continuous event) 68 percent of the time, versus 23 percent of the time for nonviolent movements. This means a violent movement is three times more likely to lead to such an atrocity. In addition, political transitions driven by nonviolent civil resistance are anywhere from over 2 to 9.5 times more likely to lead to a democratic outcome. They are also approximately one-third less likely to result in civil war.

Some people may argue that violence works faster than civil resistance, but that premise is also not supported by the data. Violent insurgencies tend to last an average of 9 years, whereas nonviolent campaigns tend to last an average of 3 years. Hopefully people understand that even if they are frustrated with the authorities, sustained nonviolent resistance is a far more likely to achieve positive change than violence.

Sudanese protesters gather in front of government buildings in Khartoum to celebrate the final signing of the Draft Constitutional Declaration between military and civil representatives, August 2019. Source: Wikimedia

To close with an example, by April 2019, five months of sustained nonviolent struggle by Sudanese pro-democracy movement ousted dictator Omar al-Bashir. He was replaced by the Transitional Military Council, which did not want to cede power, and in June 2019 it ordered hardened militias to attack and commit atrocities on supporters of the nonviolent movement. The governments of Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, and Egypt all supported this effort, offering funding and even personnel. The pro-democracy movement responded by calling a general strike. This tactic showed the Transitional Military Council that repression would never yield the result it wanted, imposing major costs on the regime and creating tension between political and economic interests. Furthermore, the regime lacked the capacity to force people back to work, which revealed its weakness. The Sudanese Professionals Association, which was a leading opposition group, stated:

“The peaceful resistance by civil disobedience and the general political strike is the fastest and most effective way to topple the military council … and to hand over power to a transitional civilian authority.”

Several months later, the Military Council was forced to negotiate a transition.

There is a science to civil resistance, but there is no formula or special tactical combination that guarantees victory everywhere. A general strike takes great unity and discipline to carry out, and may not be appropriate for all movements at a given point in time. But from the basis of its own unity, strategy, and nonviolent discipline, the movement in Sudan used this tactic to respond effectively to the challenges and opportunities in its environment.

Similarly, the futures of movements in other places are in their own hands, and history will be written based on the choices they make.

This article has also been translated into Spanish.

Hardy Merriman

Hardy Merriman is former President & CEO of ICNC. He was also a senior technical advisor at USAID’s Powered by the People program and a principal investigator of the “Fostering a Fourth Democratic Wave” project at the Atlantic Council. Mr. Merriman has worked in the field of civil resistance for over 20 years …

Read More