Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Kara Kingma NeuOctober 04, 2018

This article is part of Minds of the Movement's Civil Resistance and Democratization series.

When activists start mobilizing to pursue a transition from dictatorship to democracy in their country, they face real risks—perhaps the most serious being lethal repression at the hands of state security forces. If feeling especially threatened, the dictator may choose to deploy the military and order it to throw its weight behind ending the popular challenge.

It is no surprise then that practitioners of civil resistance have long advised that a key part of campaign success—and campaign survival—is shifting the loyalty of the military away from the dictator and toward the opposition. This aspect of civil resistance captured my attention as a master’s student in late 2010, when the Arab Spring uprisings broke out. Why, for example, did the Egyptian military defect, while the Bahrain military did not?

Military defections may involve deployed soldiers rethinking their shoot-to-kill commands, the military leadership publicly announcing its removal of support from the regime, or something in between. Military defections weaken the dictator and hasten his fall.

Military fraternizing with protesters, Egypt, 2011. Source: Flickr user Alisdare Hickson/Wikipedia (CC BY-SA 2.0).

Having achieved campaign success, though, activists and would-be democrats face a new challenge. How do they establish a civilian-led, democratic political system? Gaining military support increases the chances that civil resistance is effective. But if democratization is activists’ ultimate goal, they should be circumspect about military involvement after the campaign and during the political transition. Militaries can leverage their position in the state to secure their interests, which might conflict with democratic political change. After President Hosni Mubarak’s fall, the Egyptian military, under the Supreme Council of the Armed Forces, appointed itself to oversee the transition. In that role, it reduced executive authority, took for itself legislative powers, and influenced the December 2012 constitution. It also seized power from the democratically elected president, Mohamed Morsi, in July 2013.

Military loyalty shifts can turn into military control of the transition, but that doesn’t mean activists shouldn’t seek military defections. My research sheds light on military involvement during anti-authoritarian civil resistance campaigns and their aftermath, to help activists and practitioners achieve both campaign success and democratization. Here are some of my main takeaways:

Takeaway #1: How A Dictator Controls His Military Matters

I find that a military is more likely to defect when a dictator has threatened its ability to carry out its functional missions effectively—that is, providing for societal stability and security. Some dictators control their militaries in ways that secure their rule from potential military overthrow. They make personnel decisions on the basis of loyalty, divide the military into competing factions, or form new security forces to counter the military. Often these strategies harm military power, autonomy, and organization, and military functional effectiveness. This generates military discontent, and disloyalty when the dictator’s rule is challenged by civil resistance.

EDSA People Power Monument representing millions of people who participated in ousting the dictator Ferdinand Marcos. Source: Patrickroque01/Wikipedia (CC BY-SA 4.0, unedited).

The size of the civil resistance campaign also matters. The more people involved, the more likely military defections become, because large size indicates that the opposition is popular and widely supported. For example, the People Power Revolution in the Philippines witnessed individuals from a wide spectrum of society joining together in opposition to the regime of President Ferdinand Marcos. In response to massive protests involving students, professionals, opposition politicians, and religious leaders, a reformist faction of the military defected, leading Marcos to leave the country.

This understanding of military defections—as caused by the dictator’s use of particular strategies to control and diminish the military—can also shed light on the military’s role during the transition. Some strategies lead to defections that are united, while others lead to defections that are fractured. This matters for the sort of challenges the military organization might pose to democratization—my research’s second key takeaway.

Takeaway #2: The Type of Military Defection Matters

To achieve the dictator’s overthrow, it is important that campaigns achieve significant and large-scale security force loyalty shifts, likely involving soldiers at the top of the military hierarchy. But activists and practitioners should know that different types of defections have different implications for democratization.

In united military defections, the military leadership decides to shift loyalty and does so on behalf of the entire military organization. The military is united and cohesive and can use its organizational strength to influence what happens after the dictator’s fall. The military will be able to pursue its own interests, like unelected positions in government and increased budgets. Civilians may have less space to make the sort of political decisions necessary for a democratic transition. In Mali 1991, the military led by Lieutenant Colonel Amadou Toumani Touré defected by arresting President Moussa Traoré. The united military leadership then set up a National Reconciliation Council composed of 17 officers to control the transition, with no civilian input as to how democratization might occur.

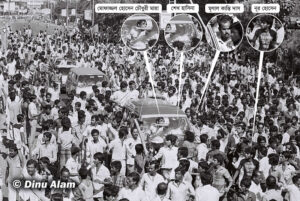

A democratic movement in 1990 led to the fall of General Hussain Muhammad Ershad in Bangladesh. Source: Dinu Alam/Wikipedia (CC BY-SA 3.0, unedited).

In fractured military defections, on the other hand, the military leadership and organization is divided or fragmented. Parts of the military shift loyalty from the dictator, while other parts remain loyal. The military is not united, cohesive, or in a position of strength, and so is unlikely to exert significant political influence. Civilians can write constitutions and hold elections and exercise civil and political liberties free from military interference. The Bangladesh military fractured in response to the 1990 anti-President Hussain Mohamed Ershad campaign. Junior officers defected and senior officers remained loyal. The military did not control the transition post-Ershad because it was too divided and disorganized. A new civilian government was able to implement oversight of the military.

What Does This Mean for Activists?

Civil resistance campaigns should aim to achieve military defections because they increase their chances of success. But they should be wary of a military leadership that, in response to the campaign, removes the dictator from power and positions itself to control the transition. After united military defections, activists must remain vigilant against military support that turns into military involvement. In the case of Mali, the umbrella opposition group forced the military leadership to include civilians in what had been an all-military interim government. The threat is smaller for fractured military defections, but remains real.

My research helps us to understand the various roles militaries can play in pro-democracy civil resistance, both positive and negative. Some of these insights may be instructive for practitioners and activists involved in campaigns that aim to bring about durable and democratic political change.

The author will be releasing additional findings and the data on which they are based in the near future.

Kara Kingma Neu

Kara Kingma Neu, PhD (International Studies, Josef Korbel School, University of Denver) is a Research Fellow at the Sie Cheou-Kang Center for International Security and Diplomacy and a Visiting Teaching Assistant Professor at the University of Denver. Kara was a recipient of the ICNC 2016 Research Fellowship award.

Read More