Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Hardy MerrimanJune 05, 2023

Humanity confronts multiple existential crises, with climate change and rising global authoritarianism both at the top of the list. Democratic governments and NGOs have made some headway in addressing these challenges, but unfortunately they have also proven inadequate or insufficient to handle the scale of adversity we face.

Yet opportunity remains. When conventional wisdom fails and standard responses seem broken, people can become open to new ideas and innovation, unified in the face of shared threats, and mobilized to play offense. One manifestation of this is increasing openness to activism, grassroots organizing, and supporting popular nonviolent movements for change. Among democratic governments and NGOs, there’s more interest now in the constructive role of civil resistance movements than I’ve seen over the course of more than twenty years working in this field.

When traditional advocacy and institutions fail, ordinary people turn toward civil resistance. Image: GotaGoHome (Sri Lankan movement for government accountability) protester on July 17, 2022 . Credit: Tennaphotography.

The reason for this interest is clear—as autocrats and demagogues dismantle institutions, and private interests corrupt politics and impede multilateral efforts, people conclude that they can no longer rely predominantly on traditional advocacy and institutional means of making change. Instead they move towards engaging in extra-institutional approaches, with civil resistance (defined here) becoming a primary option.

Recognition that civil resistance movements are essential to overcome our current crises is progress, but it’s only a first step. Additional work is needed to coordinate movement support and increase its impact, including:

1. Developing shared theories of change about how to support movements (the topic of this blog post).

2. Identifying specific best practices, principles, and frameworks for movement support (this topic is covered in the recently-released report Fostering a Fourth Democratic Wave: A Playbook for Countering the Authoritarian Threat).

3. Developing infrastructures to sustain the field of civil resistance, including practitioners, scholars, and movement-support organizations (I address this topic of my next blog post).

Developing shared theories of change

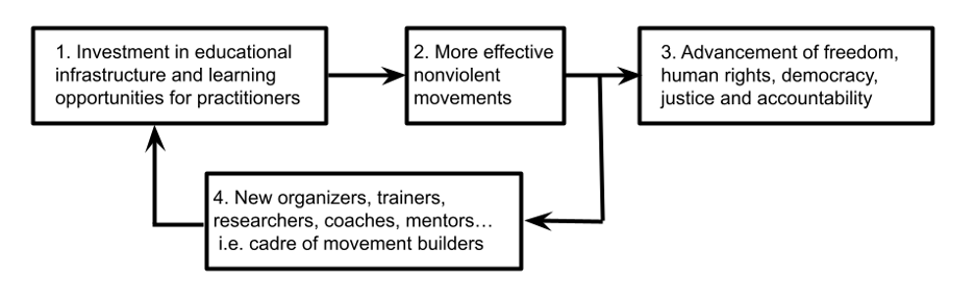

There are multiple theories of change that can guide support for movements. The one I will present here is foundational to the work of the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict’s (ICNC), and it consists of the four steps outlined below.

1. Investment in educational infrastructure and opportunities for practitioners

Being a movement organizer is one of the hardest, and most important, jobs in the world.

In recognizing this, people tend to focus on the challenge that a movement’s adversary presents. However, a further major obstacle is that—unlike virtually any other vocation—there are often few or no formal structures available to support knowledge and skill acquisition by movement organizers in their particular context. Instead, many movement organizers learn on an ad hoc basis, and then face strategic and tactical choices with massive consequences for themselves and their movements.

Predictably, as autocrats have systematically invested in their own skills and capacities to counter movements over the last two decades, movement success rates have declined. A commensurate investment by external actors to support the skills and capacities of movement organizers is needed to level the playing field. Movement allies and supporters owe it to organizers to do much more in this regard, and this is one of our greatest opportunities for impact.

The competencies, skills, knowledge, and connections that movements need over the course of their growth are diverse, and can include:

• Techniques of movement organizing

• Strategic planning for movements

• Civil resistance

• Research

• Knowledge of national, provincial, and local institutions

• Issue area expertise

• Negotiations

• Coalition building

• Public communications

• Technology

• Recruitment and management of volunteers

• Training

• Conflict resolution

• Domestic law, and potentially international law

• Fundraising

• Budget management

• Electioneering

Of the above list, some of the rarest and most valuable assets are knowledge, skills, and connections related to movement organizing, civil resistance, and strategic and tactical planning.

Investments in education infrastructure aim to increase the availability, depth, and localization of these assets, through two approaches. First, every community has their own organizing traditions, movement history, and activism cultures. Investments in educational infrastructure seek to make this knowledge and its practitioners more accessible within a society, as well as to distill local insights so that others can learn from them across borders. Second, educational infrastructure aims to distribute research findings, planning frameworks, and insights from other movements (i.e. internationally) to local actors. This combination of local knowledge possessed by grassroots groups, alongside more generalized insights from scholarship and lessons learned from other contexts, can powerfully catalyze movement growth.

Participants engaged in a training exercise at during a 2017 ICNC-sponsored training entitled "Learning Nonviolence for Participatory Citizenship and Democracy" in Pakistan. Credit: Mariam Azeem.

Elevating both local and generalized forms of knowledge can be done in many ways. For example training, education, and skill-building activities can take place in-person or online; be organized within a movement or by external parties; last for hours, days, weeks, months, or years; cover narrow or broad topics; and focus on general education, specific campaign planning, and/or practice. They can also take the form of one-off events or be part of a sustained educational and skill-building process.

Such efforts are also often combined with (and sometimes preceded by) distribution of educational materials such as books, articles, movies, and simulation games. In addition, learning-by-doing (especially when supported by coaching and mentoring) increases the skill level of activists and organizers who report that educational support is what they want.

Furthermore, movement allies–such as staff at philanthropies, advocacy NGOs, diaspora groups, and governments–can also benefit from training and education to increase the effectiveness of their movement support practices. Like grassroots organizers, many of these allies lack structured opportunities for learning about civil resistance movements in their particular vocation.

Because contexts and constituencies are diverse, there is no one-size-fits-all solution for every movement’s educational needs. As such, investment in educational infrastructure must foster a range of capacities, including offering research, development of educational materials, development of skilled trainers, network building, coaching and mentorship, and other products and processes.

2. More effective nonviolent movements

We invest in educational infrastructure for practitioners because research (i.e., here, here, & here) and experience tell us that the strategic and tactical choices of movements help them to overcome adverse structural conditions and powerful opponents. Therefore training, education, and skill-building efforts are a cornerstone of building effective movements.

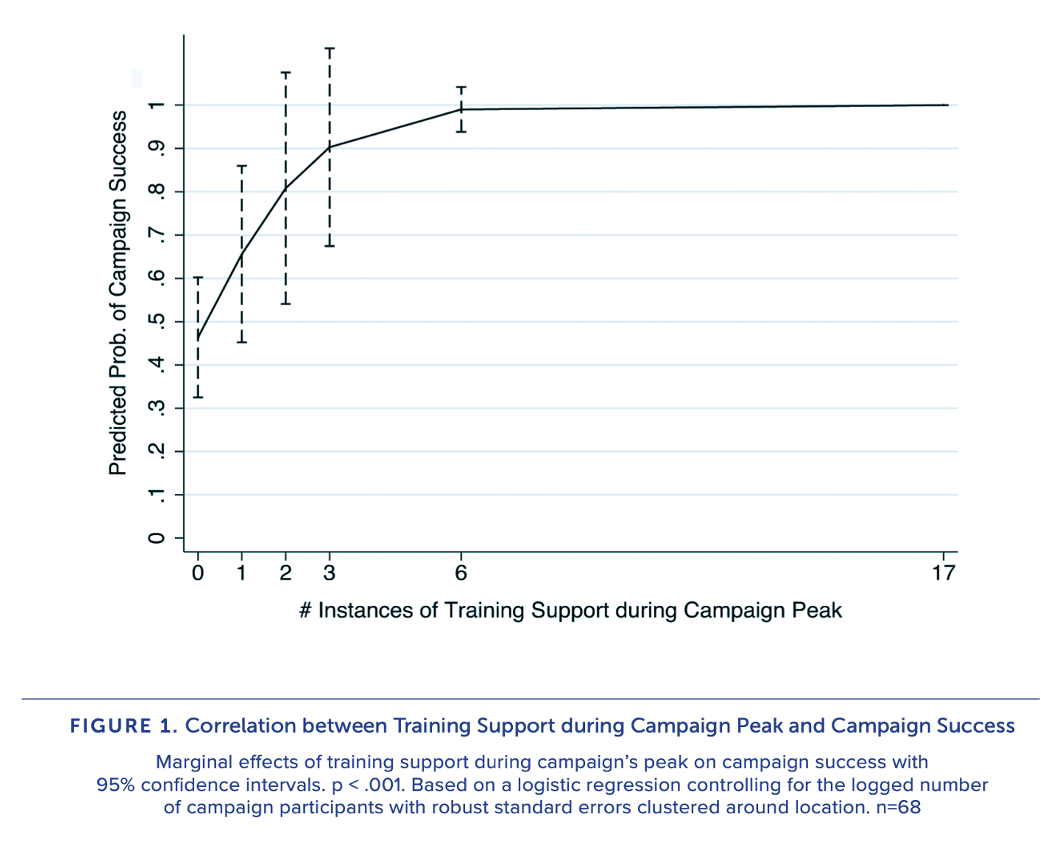

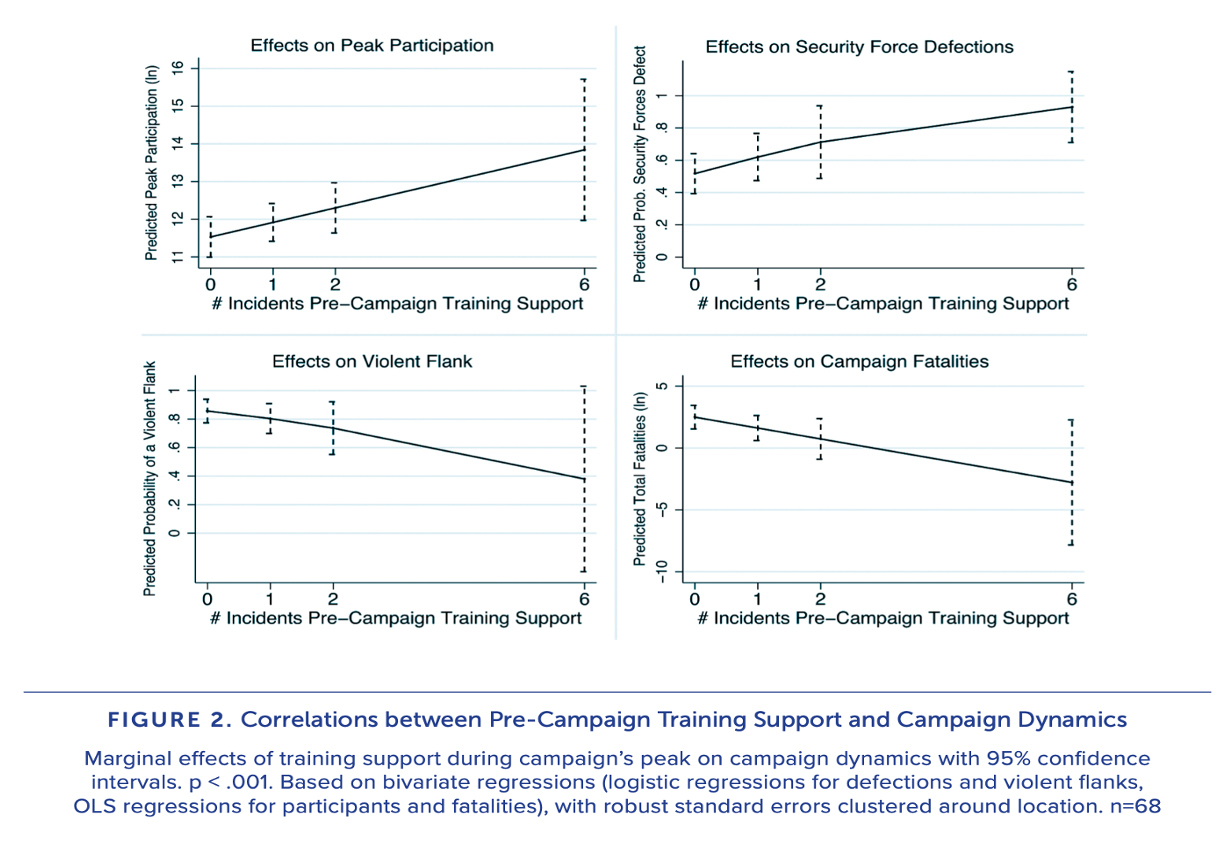

Source: The Role of External Support in Nonviolent Campaigns: Poisoned Chalice or Holy Grail? by Erica Chenoweth and Maria J. Stephan.

Source: The Role of External Support in Nonviolent Campaigns: Poisoned Chalice or Holy Grail? by Erica Chenoweth and Maria J. Stephan.

A recent comprehensive study of a wide range of forms of external support to movements strongly validates this point, and finds that training in organizing and civil resistance are the most consistently positive external interventions to movements. Quantitative analysis finds that movements that receive training prior to mobilization “are much more likely to mobilize campaigns with high participation, low fatalities, and greater likelihood of defections.” Qualitative research and ICNC’s own monitoring and evaluation efforts also find that educational programs are a critical way in which activists connect to each other and form networks of mutual support that persist over time.

3. Advancement of human rights, democracy, and accountability

Established research (i.e. here, here, & here) also tells us that civil resistance is one of the most powerful drivers of human rights, durable democratic gains, and accountability over the last century, as well as in recent decades. Civil resistance movements have achieved such gains in autocracies, as well as in democracies where they have been essential to the defense and expansion of democratic rights and protections.

By increasing movement effectiveness through educational efforts, we therefore powerfully increase the probability of movement-driven advances in rights, freedom, and justice. When such advances occur, they also create a conducive environment for additional investments in educational infrastructure (reinforcing stage 1 of this theory of change), as newly democratic societies can become hubs of learning for other organizers in a region.

4. New trainers and knowledge redistributors

Rhize is an organization that stimulates organizer-to-organizer education. Credit: Rhize website.

A further outcome of movements is the growth of activist experience, knowledge, and networks, which collectively expand the talent pool from which new educational infrastructures in the field can be built (thus, cycling back into stage 1 of this theory of change).

Yet at present, more often than not, organizers and activists end up moving into institutional politics and advocacy, which diverts their energies and talents away from educating the next generation of organizers. This happens because supportive infrastructures exist for these institutional career paths, but opportunities are comparatively lacking for sustained work in movement building, and civil resistance education, and training.

Therefore, to ensure that these talented organizers and their experiences, knowledge, and networks are not lost to the field, they must be offered opportunities to become knowledge redistributors for others. This can happen through offering additional mentorship to build their knowledge redistribution capacity (i.e. as writers, trainers, researchers, or other roles), fostering their communication skills (i.e. verbal, written, digital), and providing funding to support their practice. In this way, they contribute to a vibrant civil society that can consolidate movement gains, support the emergence of new movements, and contribute to an ecosystem of learning, network building, and mutual support.

Developing infrastructures to sustain to sustain this kind of work—and the field of civil resistance as a whole—is the topic of my next blog post. Other established disciplines and vocations have an organized ecosystem of entities that support them—we should learn from their example and adopt, adapt, and invest in structures that sustain the people, knowledge, networks, and opportunities that enable the field of civil resistance to grow.

Hardy Merriman

Hardy Merriman is former President & CEO of ICNC. He was also a senior technical advisor at USAID’s Powered by the People program and a principal investigator of the “Fostering a Fourth Democratic Wave” project at the Atlantic Council. Mr. Merriman has worked in the field of civil resistance for over 20 years …

Read More