Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Phil WilmotDecember 19, 2023

Last fall, I participated in the Copenhagen People Power Forum, which brought together movement leaders from all over the world to speak with leaders in public, private and humanitarian sectors to critique and advise the forms their solidarity with movements can take. It was an immense effort toward globalizing our struggles, but as with any other recent global gatherings, many invitees from Africa and elsewhere were unable to attend because of visa denials/delays at destination and transitory country embassies.

Hardi Yakubu, activist and coordinator of the Pan-African movement Africans Rising, addressed a Danish politician from the audience during the Copenhagen forum: “It is extremely difficult to come to a place like this, especially for people from Africa and other global south countries. We have to answer dehumanizing questions, pay a lot of money, surrender our banking documents, and still have no guarantee of getting the visa. Many people missed their visas despite applying well ahead of time. We have to stop visa privatization, which is used to implement this xenophobia.”

In these times, our movements must be able to meet and cooperate. Immobility is a barrier to victory in a world where injustices increasingly transcend national borders. Fortunately, movements across the planet are materializing for border justice, and some for total border abolition. Their adversaries are elusive and seemingly unidentifiable. Their tasks are monumental. How can a traveler a continent away from their destination even begin to wage a struggle against such powerful, distant and insulated forces as "immobility"? Is it enough to hold actors of border injustice accountable? And more broadly, why do border justice movements matter?

Border injustice and immobility form a multi-faceted and under-studied category of struggles. A few concrete examples of such movements—ranging from a very local struggle to abolish a border tax on Ugandan market traders, to a Pan-African struggle for a borderless Africa—provide anecdotal insights on how activists leverage nonviolent action to fight for mobility rights.

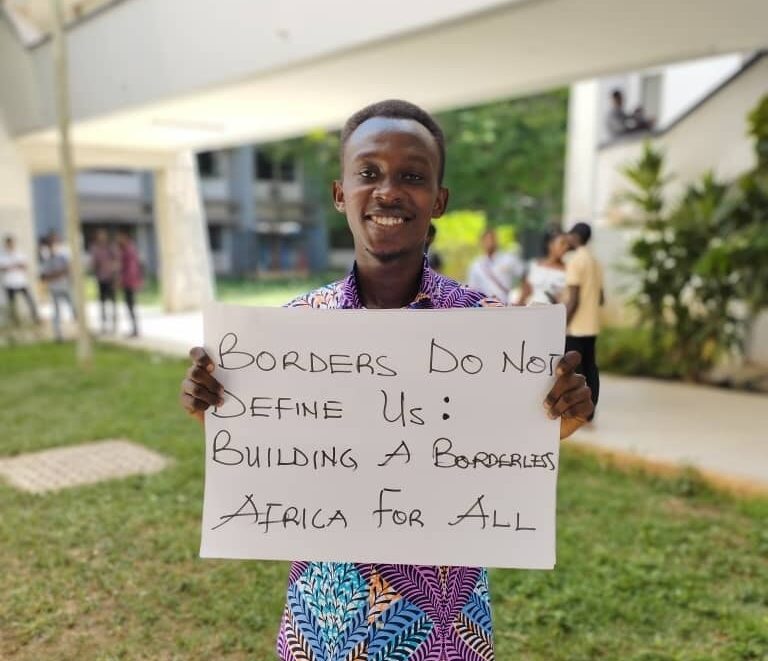

2023 International Day of Solidarity with Sudan. Organizations like Africans Rising and Kayole Community Justice Center model the borderless Africa they wish to see by engaging in Pan-African activism. Credit: Kayole Community Justice Center Facebook page.

Nonviolent struggles against border injustice

When the local government of Ugandan border town Busia introduced a new tax in 2019 for small traders and farmers selling their vegetables on a daily basis to neighboring Kenyans, the traders and farmers blockaded the border and stormed the local tax authority office. How could it be, they reasoned, that land-grabbing, tax-dodging companies of Uganda continue to enjoy free passage when exporting tons of sugarcane through the border point, yet an unemployed person carrying her greens for sale by foot forks over every coin she has? The rapid actions of Busia residents forced Busia’s local government to scrap the regressive tax.

As useful as border justice actions may be, they are incremental and often momentary gains. Border abolition requires strategy at higher levels, targeting both public and private sectors at numerous points in transitory and destination countries. Thus, while this first example presents a single adversary and thus a relatively concrete path for popular community action, other mobility rights movements are happening on much broader geographic terms, and this introduces greater strategic complexity.

Credit: Africans Rising.

During a Borderless Africa campaign launched on African Liberation Day, May 25, this year, border communities organized all manners of tactics to loosen state grip on mobility: a poetry show in Zambia, teach-ins at Congolese schools, marches along the sealine in Madagascar and the highways of Botswana, a football match at the Aflao border between Ghana and Togo. All of these actions and more across the continent undergirded a People’s Petition for a Borderless Africa launched three months prior.

Further, Borderless Africa is lobbying the African Union (AU) to expand mobility across Africa for Africans. If they can persuade at least 16 more countries to ratify the AU protocol on free movement, it will trigger implementation. The overall goal is an African passport available to all Africans, including those in the diaspora. But this is no easy task, for the more borders involved, the more intricate campaign organizing must become.

Identifying the big fish

The most ambitious movements for mobility rights cannot afford to underestimate the complexity of the adversary landscape—especially companies that make the policing and control of human movement possible. The Transnational Institute has identified five key sectors actively investing in more extreme militarization of borders: border security (including monitoring, surveillance, walls and fences), biometrics and smart borders, migrant detention, deportation, and audit and consultancy services. Their report profiles 23 key private corporations involved and proposes divestment campaigns as a means of pressuring for better mobility, especially for refugees.

This information is extremely valuable for border abolitionists, since they can break down the adversary landscape and target just one of these “big fish” actors at a time. Instead of seeing “borders” as the adversary, they can see borders as the system of injustice being held up by given pillars of support (the five key sectors). Persuading or inducing defections in one or two of them for example, as Rainforest Action Network knows, can shift the power away from these actors, toward those fighting to abolish borders.

Credit: Hardi Yakubu's Facebook page.

Borders built on violence

The privatization and autocratic nature of the border industry underscores what artist-architect Frederick Hundertwasser (often cited by Adbusters, which has long been committed to border abolition) once said: “The straight line is godless and immoral.” Nation-state borders—many of them literal straight lines in the sand—are death. Built on violence, they nurture more and more violence, an invisible but unduly-honored blaze separating our species from its water sources, schools, better economic opportunities and loved ones. For the movements discussed in this post and many others, without borders, humans are more capable of healing the wounds they’ve incurred from past and present violent systems, like colonialism and capitalism.

Why do border justice movements matter? Because organizing grassroots cooperation across millions of diverse members on our planet is something that our movements would benefit from. From the First International to the Industrial Workers of the World to the Zapatista Intergalactic, internationalism is part of our revolutionary DNA. In recent years, our struggles have become even more transnational, because the systems that oppress us are increasingly globalized. We cannot afford to limit ourselves to local activism in an age where internationalism is essential for victory.

Phil Wilmot

Phil Wilmot is a former ICNC Learning Initiatives Network Fellow, co-founder of Solidarity Uganda, and a member of the Global Social Movement Centre and Beautiful Trouble. Phil writes extensively on resistance movements and resides in East Africa. Write to Phil at phil@beautifultrouble.org.

Read More