Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Mariam AzeemDecember 27, 2017

In my previous blog post, I shared with you my personal journey to becoming a civil resistance trainer and outlined a few takeaways about effective training approaches. In this post, I expand on those takeaways, which I hope civil resistance trainers in other parts of the world can use to improve their work. Our roles are to:

Enable Movements to Learn from the Past

A movement can draw mass participation through emotion and passion, but sustaining itself is difficult when its members do not have prior knowledge of historical episodes of civil resistance. Mapping and discussing past movements enables activists to learn new ideas about, for example, dealing with repression.

As a civil resistance trainer, I often use storytelling to facilitate this type of learning. Storytelling is a very technical tool. It has advantages and limitations, especially for those who are interested in social justice. A participatory methodology in non-formal education, storytelling makes it easier for participants to retain important incidents, identify and understand trends, and follow a logical progression of events in civil resistance history. On the other hand, it is important to carefully customize the content and context for specific audiences — without changing history or the essence of the story.

What I do during training is divide participants into groups and assign a certain movement to each of them. The groups prepare to tell the history of the movement through storytelling, with other participants as their audience. Some of them even act out the story the form of a play or TV show.

Editor's note: Screening films about past movements can be useful storytelling tools. Some options that are available for free online include Budrus (and the graphic novel in Arabic here), Eyes on the Prize, and Salt of the Earth. For something more personal, check out this TED Talk about how a social justice organizer first got involved in a nonviolent movement.

Facilitate Analytical Thinking

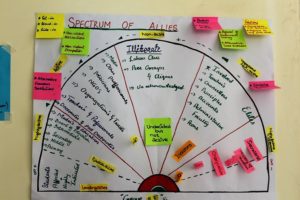

Analyzing a full spectrum of possible movement allies and opponents is a crucial part of strategic planning for nonviolent movements. Trainers may use an exercise called the Spectrum of Allies to help movements identify groups whom they may want to engage, either by emboldening them in their resistance (if the group or individual is identified as a passive, not strong, ally), neutralizing them (if the group or individual is identified as a passive, not strong, opponent), and so on. (Ed: See pg. 208 of the Handbook for Nonviolent Campaigns, 2nd Edition, War Resisters’ International; see also ICNC’s Resource Library for translations of the exercise into seven languages.)

The Pillars of Support exercise is another useful analytical tool (ed: see pg. 203 of the Handbook for Nonviolent Campaigns). It helps movements identify groups, systems, and institutions in their societies that prop up power holders. The tool (ed: which has also been translated into numerous languages) enables movement participants to think more strategically about the nonviolent methods to engage in, and perhaps also in what sequence.

These tools help participants think critically and expand their perspectives—and to do so as a team. They are extremely beneficial in mapping available resources and options, plus they can be fun to use.

Enable Movements to Sustain Themselves

Meaningful and long-lasting movement participation depends on many factors. One important factor is participants’ sense of ownership or buy-in in the movement. Do they feel like they are contributing to planning, actions, and vision in meaningful ways, or like they are just another body in the crowd?

One thing trainers can do to increase participant ownership of the movement is communicate with everyone who is part of the movement, not exclusively with leadership. Trainers should also encourage movement leaders to adopt a feedback mechanism that allows participants to express concerns, ask questions, and make suggestions (ideally in an anonymous way if they wish).

Source: Author.

Another way trainers can encourage participant buy-in is the “fishbowl” conversation. There are several variations of the fishbowl conversation, but the basic idea is that four to six chairs are arranged in a circle (forming the “fishbowl”)—one of which remains empty throughout the conversation. All other chairs for participants are arranged in concentric circles outside of the fishbowl. As those who are sitting in the fishbowl begin discussing or debating an issue, others from outside the fishbowl may approach the empty chair to join the conversation. However, when someone does so, another person in the fishbowl must leave, so that one chair remains empty.

Finally, language plays a vital role in the training process and in movement building. It is important for trainers to use inclusive and broadly relevant language. Two tips I have learned along these lines include:

- Post definitions or translations of keywords and relevant acronyms in the training hall for the duration of the training.

- Post community guidelines with regard to language inclusivity in the training hall for the duration of the training.

Operate on Decentralized Leadership Principles

Sometimes trainers may share a vision for the common good, but they engage in non-democratic actions in their trainings. Trainers must demonstrate through words and action that power is shared and multi-layered.

For example, I once observed that the participants of a training were not showing up on time each morning. Even those who managed to do so were very sleepy during the day and displayed very low energy levels. I came to understand that many participants earned their living with night jobs, not the usual nine to five schedule, making it very challenging for the group to reach the training session early in the morning. To resolve this, we as trainers suggested two time options that they could decide on through group deliberation.

This action brought positive results. Because participants were directly involved in planning the training, it became possible for them to be punctual—and punctual they were. In short, trainers must focus on participants’ needs, which vary from person to person and from day to day.

Train Minds and Hearts

Source: Author.

Movements are first and foremost a human-driven phenomenon, and trainers must not forget this. To help prepare participants mentally, emotionally, and physically for the challenging and often uncertain work of activists, I remind them that a civil resistance struggle may carry on for an indefinite period of time and still not achieve its objectives. Participating in such a struggle may stir a variety of emotions, such as frustration and hopelessness (ed: see also Joel Preston Smith’s recent post).

If movement builders and participants do not learn how to deal with pain, fear, anxiety, and frustration, they may have a higher risk of engaging in violent acts during civil resistance, or of experiencing physical and mental trauma during and after the movement. One way trainers can prevent this is by opening up space during trainings to discuss mental, physical and emotional concerns. Knowing that others are suffering from similar issues can help participants connect with one another, which boosts solidarity, the very foundation of nonviolent movements.

On a more practical level, trainers may encourage movement builders to form healing and well-being groups with health experts (whether inside the movement or trusted allies), whose work will continue to support and accompany the movement over a sustained period.

In the end, the role of a civil resistance trainer is to help movement actors understand that the process of organizing and conducting nonviolent actions is equally as important as achieving the movement’s objective. In other words, the journey is the destination.

As Maciej Bartkowski, Markus Bayer et. al., Hardy Merriman, and others have argued on this blog, there is intrinsic value in the institutions, processes, approaches, and actions that movements create in carrying out their work. Movements should aspire to espouse democratic principles and construct operating bodies that outlive the movement’s lifespan, that offer themselves up to the society of tomorrow—and trainers can help them achieve this. Going one step further, trainers can also help movement actors reflect on and, to the extent possible, safely document their lessons learned for future generations of the movement and for other movements around the world.

Mariam Azeem

Mariam Azeem possesses nearly fifteen years of experience and expertise in the field of education, training, and coaching for nonviolent civil resistance, human rights, women’s leadership, and movement building. She supports and facilitates youth, women, and gender and sexual minorities in advancing their narratives of human rights and justice.

Read More