Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Yunus BerndtAugust 26, 2020

Contrary to what one might have expected, activism since the outbreak of Covid-19 has not gone into hibernation. The vigorous reincarnation of the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States and around the world, the revived movement in Hong Kong, and recent protests in Serbia, Japan, Israel, and anti-dictatorship struggle in Belarus, to name a few, are evidence that activists and citizens who want change in their countries are far from isolating themselves in secluded dens.

What we can say instead is that people have rushed to reinvent their campaigns since the beginning of this crisis. Some shifted their focus to community support, lockdown monitoring, and popular education. Others reassessed methods of conveying their message.

One of them was Europe Must Act, a pan-European nonviolent movement calling for the evacuation of refugee camps in Greece. I was fortunate to participate in the organization’s process of rethinking campaign strategy and thereby engineered, introduced, and helped implement the concept of peopleless protests.

A peopleless protest is, as the name says, peopleless, at the moment of its digital capture, assemble and release to the public. Such protest occurs simultaneously offline and online: Participants place a placard, object, or drawing in public spaces separately from each other; then they take a picture of this symbol of their protest and upload it on the campaign’s website. Once online, all these individual contributions get assembled to a joint demonstration through a video, timeline, or map.

What exactly this symbol is, during which time period they should be placed in public, and whether they are linked together through a gallery or map is up to the campaign organizers. Meanwhile, the number of possible participants depends on the campaign's reach and is, in theory, unlimited.

A how-to video explaining to supporters how to participate in the protest. Source: Europe Must Act.

Leap in Time: Analyzing the Context

Footprints in front of the German Bundestag. A peopleless protest dubbed “Leave No One Behind” of the German NGO Seebrücke. Source: SEEBRÜCKE Schafft Sichere Häfen! Flickr account (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, unedited).

To understand this better, let us jump back to March 6th, 2020. On that day, Europe Must Act was planning pan-European demonstrations for the immediate evacuation of refugees from overcrowded camps on the Aegean Islands, Greece. Yet it became clear very quickly that traditional, physical demonstrations would be impossible as Covid-19 was gaining a foothold across Europe.

At that point, we asked ourselves three crucial questions, which, by the way, merit consideration by any movement wondering whether peopleless protest could be a viable path.

First, is it reasonable to call people to the streets right now? To answer this first question, we considered the public health and legal risks, whether supporters would be able to travel to the gathering or if they were locked down because of the public health emergency, and whether a physical demonstration might provoke a public backlash for allegedly ‘irresponsible behavior’ and potentially obscure our demands. At the time of this discussion last March, we felt urged to respect strict physical distancing guidelines issued by health authorities and decided against a traditional protest.

Second, are we capable of transitioning to a social media campaign governed by tricky algorithms? These platforms are designed for commerce, not for democratic participation. Do we have a significant budget for marketing? Do we have connections to celebrities and/or droves of data analysts? In other words, do we have a chance of reaching anyone beyond our bubble? We did not have these resources and thus ran a risk of being ineffective if we did not make an effort to bridge our online efforts with offline actions.

Finally, whom do we want to include in the protest? Not everyone has Internet access (think of the digital divide) nor social media accounts. For those who do: How reluctant are they to share a selfie and personal data with notorious tech giants? As a result of this questioning, we aimed to open participation up even to people who did not use social media, while respecting privacy rights (by keeping the data anonymous and not requiring people to post on their social media accounts).

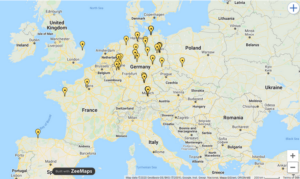

Click to enlarge. Assembling of the individual contributions to the peopleless protest using a mapping application. Source: Yunus Berndt/Europe Must Act (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, unedited).

The concept of peopleless protests responds to these preconditions and we implemented it through the campaign ‘Silhouettes of Solidarity.’ As campaign organizers, we opted for silhouettes as the symbol, a very graphical representation of the human protester. We scheduled the campaign to end on March 26th and used a map to create the virtual assembly. We compiled two how-to clips, coalesced with partner NGOs, and spread the word (social media and through our partner organizations word-of-mouth and newsletters. We also phoned people we know and explained the idea). Participants could upload their silhouettes directly to our map, email them to us, or share them with us on social media.

The result: Within a week, incredibly creative activists chalked their silhouettes on sidewalks, painted them on their windows, cut them out of cardboard, and sent us pictures from places as dispersed as Oakland (USA), Wroclaw (Poland), Norwich (England), Asturia (Spain), Berlin, and Paris. We gathered online and in real life with silhouettes from across the world and brought peopleless protest to life.

Looking Forward: Spreading a Concept to Increase Democratic Resilience

Footprints of the peopleless protest “Leave No One Behind” of the German NGO Seebrücke. Source: SEEBRÜCKE Schafft Sichere Häfen! Flickr account (CC BY-NC-SA 2.0, unedited).

Peopleless protest is intentionally an abstract concept, rather than a singular campaign, to allow other movements to benefit from adopting the fundamental idea. In part, the term has already spread much more quickly than its theoretical foundation, leaving the practitioner who tries to learn about peopleless protests quickly puzzled.

First of all, peopleless protests are not a mere social media campaign. Hashtag-based campaigns, for example, can indeed be a powerful tool, as we saw during the #BlackOutTuesday campaign against racism and police brutality. But my experience has been that creating momentum on social media is beyond the capacities of small and regional campaigns. You basically scream into a wide-open space and only those who already know your cause listen. To attract the attention of someone beyond your circle, there needs to be a parallel activity in the physical world, as with a traditional demonstration.

Peopleless protest, as we conceived it, requires three interrelated elements: Individuals placing symbols in public places separately from each other, recordings of these symbols, and a linkage of these digitized pieces online.

However, there have been some interesting cases where these conceptual borders were crossed. One example is to inverse the process: Activists connect with each other in the virtual space first, collect individual contributions, and then assemble them in the real world. Following this idea, MoveOn.org planted individualized signs on the West Lawn of the U.S. Capitol representing health-care workers who were demanding more personal protective equipment. And in Germany, Fridays for Future laid down placards in front of the parliament. This gives hope that the ongoing crisis is not only a trigger for people to rise, but a trigger to reimagine how we rise.

In whichever form, peopleless protests are a viable alternative to traditional demonstrations whenever social distancing is the order of the day, as during a pandemic or a curfew, as well as whenever people are permanently socially distanced (such as rural communities scattered around a country or, for that matter, people placed under house arrest by a repressive regime). At the same time, peopleless protests are one approach to minimizing subjugation to social media algorithms and the exclusiveness of the Internet. They can thus broaden political participation in times when freedom, justice, and democracy are suffering from a pandemic, or simply are at risk of violent repression—a timeless challenge for movements around the world today.

Yunus Berndt

Yunus Berndt is the founder of the Maltese NGO Hal Far Outreach and former activist with Europe Must Act. He holds a B.A. in International Relations and Management and focuses his research on migration, post-modernism and entrepreneurship.

Read More