Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Mariam AzeemMarch 01, 2022

I am Director of Movement Support and Learning at Rhize, and manage a six-month long Global Coaching Fellowship (GCF) program that includes coaches (trainers) working with/for movements across Africa. This experience has given me insight into practices used by coaches in the field, which has allowed me to maneuver GCF design accordingly.

Last year, I read Hardy Merriman’s blog posts about civil resistance training and activists’ common questions about training, and so much rang true to me. I am a fan of learning theories around movement support work and in-field tools and practices used by coaches and activists. Hardy’s fantastic blog posts inspired me to gather in-field experiences of GCF coaches to share them with Minds of the Movement readers.

Several weeks ago, I reached out to five coaches who participated in the GCF and who are based in Uganda, Malawi, Zambia and Nigeria. The coaches work with a wide variety of movements, including but not limited to land rights, women rights, sexual health and reproductive rights, LGBTQI rights, and climate justice and environmental protection. Building on some of the questions in Hardy’s posts, I interviewed each of them, and there were so many valuable insights that I had to split them into two parts, with some of their answers below, and others included in a companion post here.

How do we find trainers and resource persons? It’s all about networking.

Photo courtesy of Rhize via Luminate.

A movement without a trainer is a movement without direction. Trainers help to shape and guide a movement in terms of strategy development, action and leadership. But how do people find trainers and resource persons?

The responses I received were unequivocal: Use your networks and ask for referrals. In other words, while you may think you have nothing to work with, the people around you already are excellent resources to tap into, and you may already know of someone with the desired skills. You won’t know unless you ask. Activists often identify people who inspire them and then approach them, request contacts, and/or invite them to train their team or be their mentors. I should note here that some trainers (like me) share their contacts after training and encourage the group to reach out to them for details.

Trainers also identify groups that are very active and radical but lack the necessary knowledge and tools to create a bigger impact. They are approached by trainers and offered support. In other words, many trainers are proactive in identifying movements to train, so the more you ask around, the more likely you will find a good resource person.

In addition, an online search via Google or LinkedIn could come in very handy. For example, activists ask their networks online (i.e. post a question on Facebook) or offline (phone calls, etc.) for trainer recommendations.

Before they launch their search, activists determine internally whether the trainer would be expected to help for free or if a fee can be set aside. To pay a trainer, activists fundraise, either asking for individual contributions or reaching out to social justice oriented funders (I offer much more on this in my second post).

When they do not have the capacity to fundraise or hire a trainer, in my experience it is important to join a consortium or network of organizations (for example, the African Coaching Network) or groups doing similar work. Through the consortium, small groups can access trainers who are from big groups but belong to the consortium for free because of the networks and relationships built. Some activists may also partner with other organizations that are already established and can provide such trainers.

How do we decide what kind of content the training participants will need? Three approaches

There are three main approaches to determining training content: Observation, external factors, and/or a pre-training assessment to understand the participants’ needs. You would then use the information gathered to set training priorities.

Observation

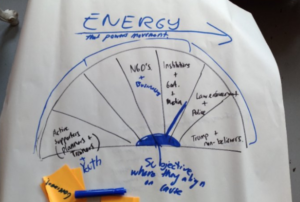

Training tool "the spectrum of allies." Photo courtesy of Rhize.

The observation approach might entail, for example, basing the training and capacity priorities on leaders’ own assessments of the historical background of the group or movement and the focus areas of their activism. Some look at the level of experience of participants and informally inquire about what they know in specific areas. This helps them to identify the knowledge gaps and thus decide what the training should focus on.

External factors

In other cases, organizers take a top-down approach and decide content based on what they themselves think the group will need, especially if the movement is engaged in a funded project with a very specific mission and goals. Organizers tend to follow what the project entails. This approach produces a training on what movement leaders or external actors want training participants to learn, which may or may not be what the participants themselves also want to learn.

Pre-training assessment

A third approach, which can be done in parallel with either of the approaches above, is to conduct a structured assessment of the target participants before the actual training. The assessment can be made via questionnaire using online tools like SurveyMonkey or Google Forms, or in-person/virtually via meetings or interviews. Remember also to take stock of the content of any past trainings the participants have already had. It is best practice to share the results of your pre-training assessment with participants prior to the training. The assessment results can be used to develop the training agenda.

In my experience as a trainer, for internally-oriented trainings, you first conduct a survey or questionnaire with the target group prior to the training so as to establish their needs. For externally-oriented trainings, you establish needs by understanding what the program aims to do (training objectives) and who the target group is (what they do and sometimes their age group).

In my second post here, I expand on these ideas and address the difficult question of finding funds for movement capacity building.

Mariam Azeem

Mariam Azeem, with nearly 15 years of experience, is a seasoned educator and coach specializing in nonviolent civil resistance, human rights, women’s leadership, and movement building. She supports youth, women, and gender minorities in advancing justice narratives. As Rhize’s Director of Movement Support and Learning (2018-2023), she trained with organizations like ICNC and the Council of Europe.

Read More