Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Rosa Marina Flores CruzJuly 20, 2023

Esta entrada de blog también está disponible en español (enlace).

Last April through early May, a group of about 150 people spent 12 days and nights traveling the roads of south/southeast Mexico, responding to the National Indigenous Congress’ call to organize a Caravan called "The South Resists". Hot days and nights, in regions where temperatures can exceed 40° C (104° F); hostile roads, where thousands of people have disappeared without a trace; hours shared with strangers, who eventually became friends, all in response to a call: it is time to organize ourselves to push back against environmental injustice and protect our lives and livelihoods.

This caravan of people walked about 1,318 miles to visited 11 destinations across seven Mexican states (Chiapas, Oaxaca, Veracruz, Tabasco, Campeche, Yucatan and Quintana Roo) to listen and share information about the threats that are afflicting the indigenous, Afro-descendant, peasant and urban peoples of this region. Large corporations and extractive projects present the majority of those risks. At each destination, nonviolent movements and local organizations joined together to receive, feed, accompany, host and organize people on pilgrimage with banners of territorial struggle.

Map of the Caravan. Credit: Informacion es poder Facebook page.

The Caravan was a physically and emotionally demanding campaign. What gave us the courage to overcome fatigue and carry on? It is our land. Although the answer sounds simple, it is extremely profound. Our corner of the world is the site of confrontation—between ordinary people and great giants, those who control the world's money. We did not go out to look for these formidable adversaries; their desire for domination brought them to where our people live, to covet our land, its water, its minerals, even the wind.

The Caravan traced a route marked by dispossession—the act of depriving people of their land and other resources—, but also marked by the struggle for life. It began in Pijijiapan on the coast of Chiapas, just a few hours from my own reality. There, women and men have been leading a nonviolent campaign to resist high electricity rates for more than three decades, because with the large electricity projects (renewable and non-renewable) that invade our territories, electricity is no longer a basic necessity. It has become a luxury good.

The southern part of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec, my Isthmus, my land of flowers, wind and sea, was the second stop. The big wind fans arrived 15 years ago, and now I can see them from my window. They are generating energy for prominent businessmen, for mining companies, supermarkets and convenience stores, for construction companies and for the army that protects them. The wind farms, 29 in total, are already installed on 32,000 hectares of indigenous peoples' common lands. We are currently facing a new mega-project: an industrial, airport, road and railroad communication complex, which will transport goods from the Pacific Ocean to the Atlantic Ocean.

The South Resists caravan meeting in Puente Madera, Oaxaca, Mexico. Credit: Futuros Indigenas Facebook page.

That is why the Caravan arrived in Puente Madera, a Binnizá (Zapotec) community that is defending El Pitayal, an area of common use that conserves remnants of dry forest. There, various collective practices are still carried out, such as collecting firewood, fruits and medicinal plants, as well as hunting for food. The Mexican state intends to demolish El Pitayal, an area where the columnar cacti that grow in the month of May produce red, sweet and very juicy fruit. It is planned to be demolished in order to build the Maquila and Infrastructure Project. But the Pitayal is defending itself, and the Caravan went to their land to show solidarity.

The route continued through the Guichicovi, Mixe territory in the upper part of the Isthmus region, where communities organized a sit-in to prevent the federal project from rehabilitating railroads to cross their villages. The compañeros and compañeras of the "Tierra y Libertad" Camp that had been installed for two months were evicted by the National Guard and the Secretary of the Navy the day after the Caravan passed; seven people were detained and released shortly thereafter.

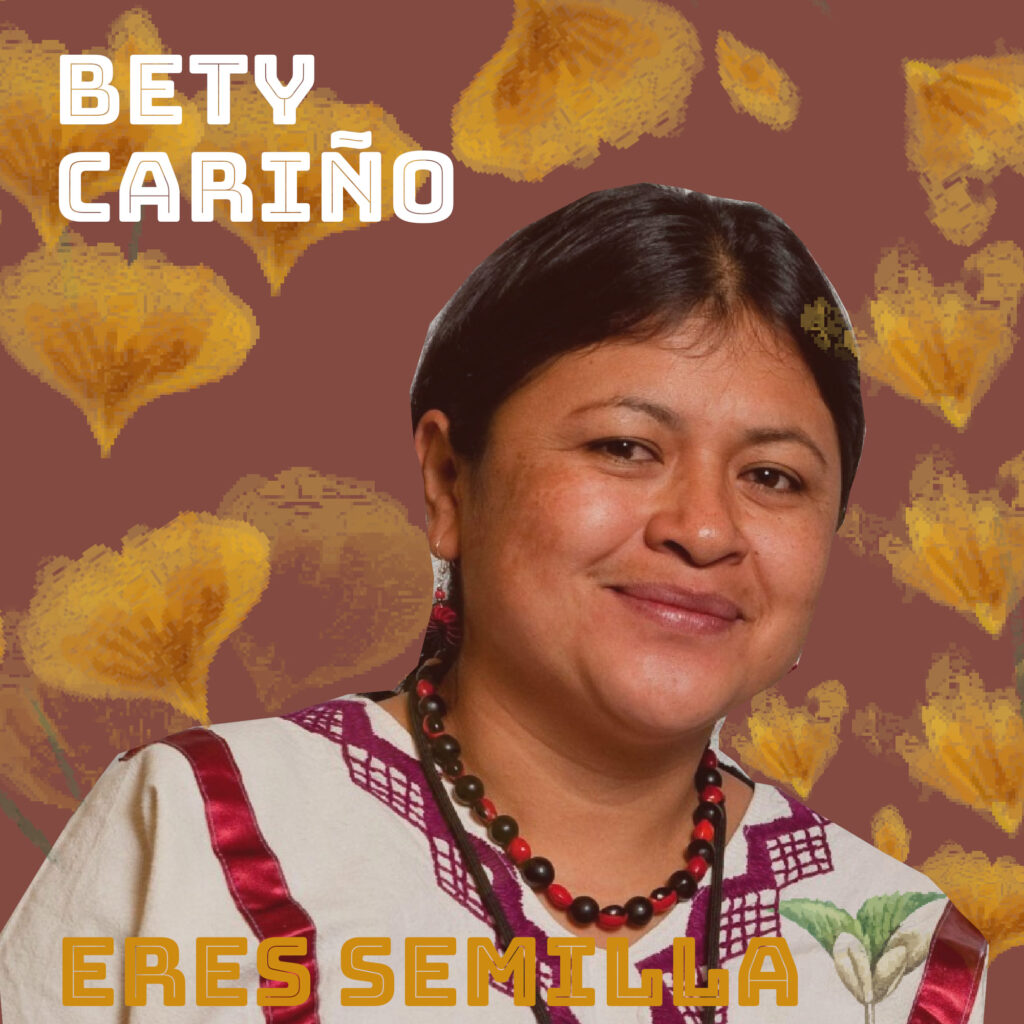

The National Guard did not cease following the steps of the Caravan for a minute. State armed forces were always vigilant and threatening. But the march did not stop; the Caravan members danced to the rhythm of Son Jarocho when they arrived in Oteapan, Veracruz, where they remembered Bety Cariño and Jyri Jaakkola whom state forces allegedly murdered in 2010 for confronting a mining company in the state of Oaxaca.

"Bety Cariño, you are a seed". Bety was a Ñuu Savi defender whom state forces allegedly murdered in 2010 for protesting a mining project in the state of Oaxaca. Credit: Futuros Indigenas Facebook page.

When the Caravan arrived in El Bosque, a municipality in Tabasco, the future caught up with them. The victims of the climate crisis indeed had faces, voices and bodies. On the seashore, only rubble remains of what five years ago was a fully functional school. Hundreds of people were displaced and are in need of solidarity. They asked the Caravan to amplify the story of their people, as a warning to others at risk of succumbing to the effects of climate change, which the Mexican government is leaving unchecked.

The Caravan entered the Yucatan Peninsula via Campeche, where the government is working on two mega-projects that are threatening indigenous territories, the Interoceanic Corridor and the Mayan Train. These projects of land speculation, jungle deforestation and intensive tourism are putting the Mayan peoples’ lives and livelihoods at risk. People from Campeche, Yucatan and Quintana Roo accompanied the Caravan's journey with their colors, with the flavors of their land and with the strength of their voices.

In Valladolid, Yucatan, the Mayan women took the lead, welcoming the Caravan and painting its vehicles with the blue paint of the ch'oj tree. They painted participants’ faces, an ancient tradition of spiritual protection before the war. In the port of Felipe Carrillo we were able to hear stories of resistance that shape the collective struggle, and how these processes have been going on for centuries. We listened to the memories of ancestral struggle that inspires the current one.

The Binniza Indigenous Community of Bridge Madera, San Blas Atempa, Oaxaca holds a Community General Assembly to denounce the Interocean Corridor project. Credit: Futuros Indigenas Facebook page.

A collective journey

The Caravan served as a space to make the various regional campaigns more visible and to accompany them. It also unified these campaigns into a broader movement and drew attention to the territorial processes at stake now that mega-projects of dispossession and the climate crisis are present.

The route traced by the Caravan marks the path of union and defense of land, of traditions, of a way of life. It crossed through lands that are under threat, but it also amplified the voices of those of us who refuse to let our territories fall victim to dispossession. Because how can we not defend what gives us life?

In this collective journey, in this shared struggle, we will continue to create new ways of thinking and acting to protect territory. The struggle and the resistance is “un camino vivo” (a living road). We are not afraid of giants, and we will continue affirming identities that converge with our struggle. The south resists and we are the south.

Rosa Marina Flores Cruz

Rosa Marina Flores Cruz is an Afro-Zapotec from the Isthmus of Tehuantepec in the state of Oaxaca, Mexico, and a member of the Assembly of Indigenous Peoples of the Isthmus in Defence of Land and Territory and the Indigenous Futures Network. She holds a Master’s degree in Rural Development from UAM-Xochimilco and a Bachelor’s degree in Environmental Sciences from UNAM, Morelia campus.

Read More