Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Aurore PruvostNovember 30, 2023

Village Prospérité, which regroups part of the nation of Kali’na in French Guyana along the northeastern coast of South America, is nonviolently resisting the construction of the West Guyana Power Plant (Centrale électrique de l'ouest guyanais, CEOG), a photovoltaic power plant coupled with hydrogen. The project launched in 2016 and the plant has been under construction since October 2022. Its completion is projected for 2024—unless the Kali’na nation succeeds at their objective to preserve their region from extractive-industry related degradation.

The plant construction requires the clearing of 78 hectares of forest in order to be set up, and the land where it is planned is vindicated and has been used for decades by the Kali’na, whose village is located only about a mile away. The plant would severely deteriorate local biodiversity: degradation of flora, fauna and the aquatic environment, with the fall-out of putting in danger protected bird species and a rare mammal, the aquatic possum.

The village of Prospérité and the CEOG project location are in a rural area, in West French Guyana, between the city of Mana and Saint-Laurent-du-Maroni, and more precisely in the natural park of Guyana, a forest. The choice of the site—along the perimeter of the regional natural park of Guyana and the nature surrounding the Saint-Anne creek—greatly astonishes the Kali’na; it is the key to their survival and, well, prospérité.

January 12, 2022: Machines deforested the equivalent of a soccer field before Kal'ina were able to physically obstruct the destruction. Credit: Village Prospérité ATOPO WePe.

Actions and allies

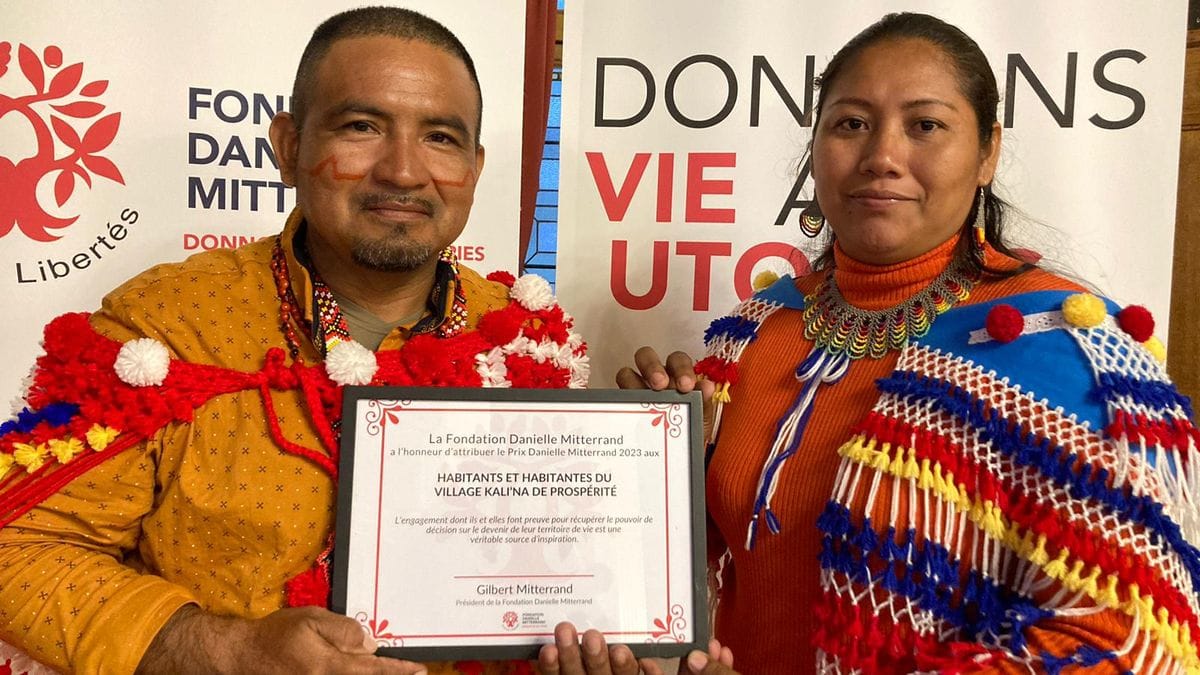

The Kali’na nation is an indigenous nation from the South-American Caribbean coast, spread over French Guyana, Suriname, Guyana and Venezuela. They are the main protagonists in the Village Prospérité struggle, but many other participants have joined the movement, such as the association AT’OPO WePe (with Mélissa Sjabere – representative of the movement) and the Indigenous Youth of Guyana (with Christophe Yanuwana Pierre – co-founder and spokesperson of the movement). In addition, the members of the village are also supported by the France-based Danielle Mitterrand Foundation, which aims to defend human rights and the living commons, and the Amerindian community of Guyana.

In reaction to the project and to leverage pressure, the movement has been using multiple tactics since the beginning of the construction work, including nonviolent occupation at the site. Since occupying the site, the nation of Kali’na obtained the departure of the deforester’s machines, but land clearing has since resumed since early March 2023.

March for Amazonia, October 14, 2023, in Paris, France. The Kal'ina receive a great deal of support from the French for their nonviolent struggle. Credit: Village Prospérité ATOPO WePe.

Some of the inhabitants of Prospérité physically opposed themselves to the tractor-mounted deforesters, which is why the deforesting machines were removed, but in the face of rising tensions in October 2022, the police intervened and arrested three people, including the customary chief of the village. This is what led the movement to escalate their actions with select dismantlement of the site.

The actions to dismantle the construction site base were executed without violence—with music and dance. Compared to the extreme violence that the plant construction is ravaging to the environment, dismantling select elements of the site could be viewed simply as a nuisance. Further, the activists felt obligated to wear masks to avoid being identified by CEOG security cameras. This action prevented the return of workers to the site for some time, but since the beginning of March, with the presence of the police, work has resumed.

French media picked up the village’s actions last year, with Le Monde publishing an opinion piece signed by about 150 people.

Video: "We the Kal'ina are only a handful of people defending our land and forest. If we were violent, these soldiers would have been dead instead of laughing..." Video footage from Kali'na land. Credit: Village Prosperité ATOPO WePe Facebook page.

What are the next steps for the movement?

Credit: This month, the Kal'ina received the Fondation Danielle Mitterrand award for their commitment to defending their territory and the rights of indigenous peoples, as well as for its village empowerment project. Credit: Village Prospérité ATOPO WePe.

During March mobilizations, tensions increased. When activists tried to enter the site, they were met with a police blockade. And as some tried to bypass the authorities, five protesters were arrested.

This escalation has provoked strong reactions throughout French Guyana. After one member of the Maïouri Nature Guyane association was taken into custody, this association denounced "the arbitrary violence used against peaceful demonstrators defending the traditional food forest of the indigenous populations of the village Prospérité." Then, on March 24, the protesters mobilized again, blocking a national road between Cayenne and Saint Laurent du Maroni. They were dislodged by the police and two protesters were arrested. The day ended with a show and a dinner in support of the demonstration.

Some key learnings

In climate justice struggles around the world, we observe an acute asymmetry between parties responsible for the injustices, on the one hand, and those resisting them, on the other. Local and indigenous struggles against extractive industries are particularly tenacious due to the nature of the conflict: just like traditional war, they are about resources and land control. In a way, they have much in common with movements resisting foreign invasion and occupation.

The future of the nation of Kali’na’s struggle is uncertain, as their escalation toward more direct actions including limited, strategic property modification have been met with equally strategic repression. Their ability to generate international attention and solidarity with their movement has been their largest success thus far, but will it be enough to put a halt to the plant construction and restoration of justice not only for the local populations but for regional sustainability?

Aurore Pruvost

Aurore Pruvost is an student at the Université Lyon III Jean Moulin, where she is completing an MA degree in International Relations with a specialization in ecological transition and Francophone regions. Previously, she was a student of the Nonviolence and Politics class at the Institut Catholique de Paris (ICP) and completed an internship with PEXE, a France-based association that works at the nexus between the environment, energy and circular economy sectors.

Read More