Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Maciej BartkowskiJuly 02, 2019

In my educational work on civil resistance with the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict (ICNC), we use different conflict analysis tools to introduce our listeners and participants to the strategic thinking and planning that goes into waging nonviolent campaigns. The most common tools that we present in our classrooms, online courses, and live trainings include: Spectrum of Allies; SWOT analysis; Pillars of Support; SMART objectives; Force Field Analysis with the Force Field Analysis Worksheet; and the MidWest Academy Strategy Chart. There are also numerous online and print guides that nonviolent strategists can consult for additional conflict analysis tools and approaches.1

In this post, I would like to introduce our readers to the strategy web of vulnerabilities and resiliencies2 — a tool that, to my knowledge, has not been used in the civil resistance field despite its direct relevance to practitioners’ work, as well as the insight it can provide to movement and campaign analysts.

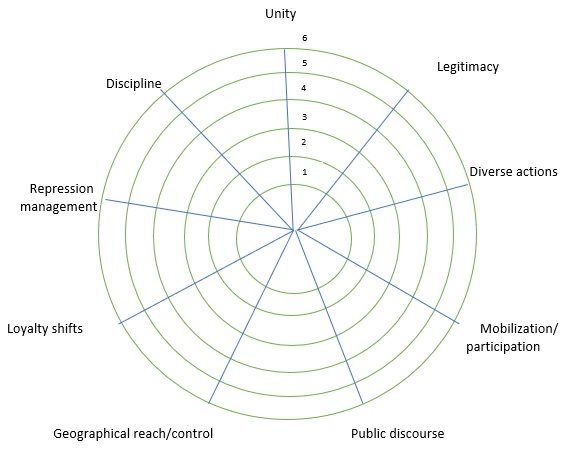

I have used the strategy web to lay out various attributes that are associated with effectively led campaigns in a nonviolent conflict (either by a movement or by its adversary). For the purposes of this exercise, I have selected nine such attributes: unity; discipline; legitimacy; repression management; diverse actions; loyalty shifts; people’s mobilization/participation; geographical reach/control; and public discourse (see Figure 1). I have also assigned numbers to the rings of the strategy web—a scale of a sort—from 0 to 6, where 0 represents non-existence of impact or non-occurrence of a given attribute, and 6 represents ubiquitous impact or presence of a given attribute.

Figure 1: The Strategy Web of Vulnerabilities and Resiliencies

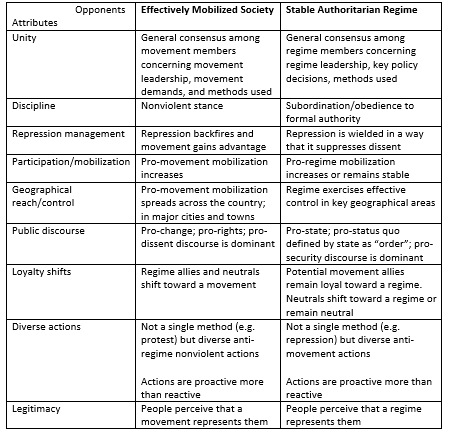

The strategy web can be used to map the attributes of an opposition movement as well as its opponent. Then one can compare the strategic gap of vulnerabilities and resiliencies between the two. Users of this tool may refer to Table 1 below, which defines each attribute as it pertains to a movement and its opponent. For the sake of the example below, I made the movement’s opponent an authoritarian regime, but this tool can apply to other kinds of opponents as well, for example a different kind of government, or a non-state actor such as a violent group or abusive corporation.

Table 1: Attributes Defined for a Movement and Its Opponent

Alternative Applications of the Strategy Web Tool

Beyond charting a conflict between a movement and a regime, the strategy web can also be used to map and compare specific civil resistance campaigns within a single movement, e.g. a bus boycott campaign and a lunch counter sit-in campaign as part of the broader U.S. civil rights movement. This exercise helps contrast the campaigns and determine which attributes are more prevalent than others—and thus which campaign attributes a movement must continue working on to increase its overall effectiveness. The strategy web could also be used to analyze the same movement or campaign but at different time intervals, e.g. at the initial, mature, or late stages.

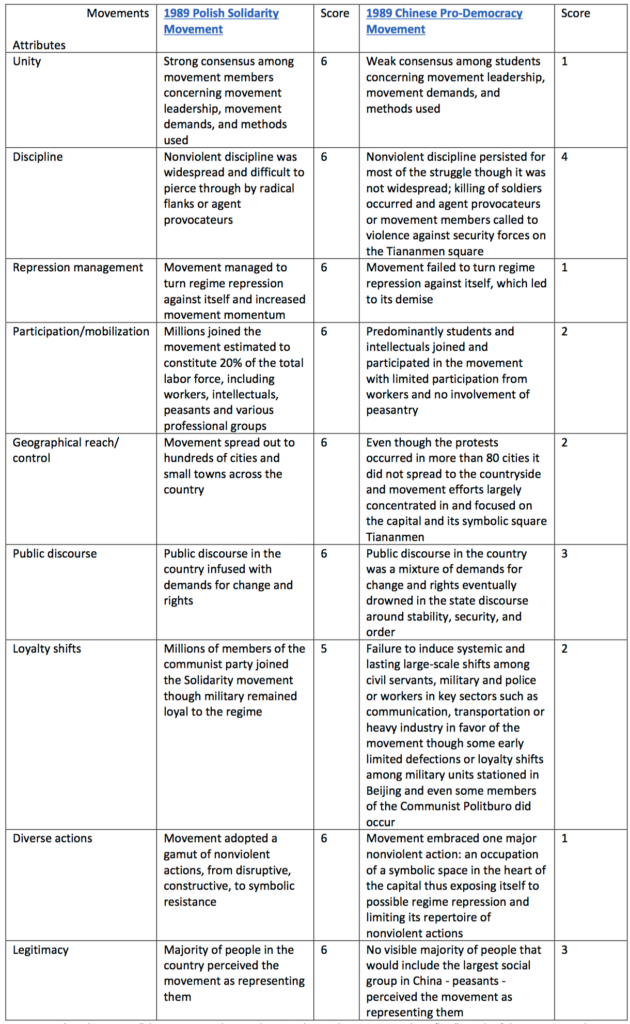

Finally, the strategy web can be applied to mapping and contrasting different movements that are taking place under specific geographies or took place at different times in different countries. To illustrate this, in Table 2 below I use the strategy web to compare and contrast two different movements: the Polish Solidarity of 1989 and the 1989 pro-democracy movement in China. The information included in the ICNC conflict summaries on these movements inform the assessment and scoring of identified attributes.

Table 2: Applying the Strategy Web to Poland Solidarity Movement vs. Chinese Pro-Democracy Movement

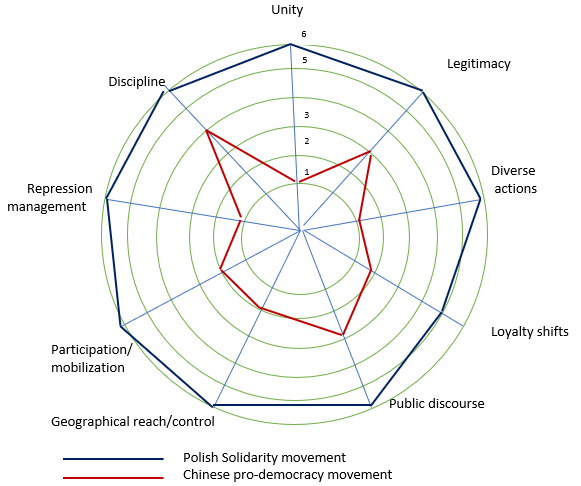

When comparing and contrasting the two distinct campaigns, we can discern at least three important patterns (see Figure 2):

- The further from the center its web, the greater the resilience of the movement. The closer to the center, the greater the vulnerabilities of the movement.

- The lesser the web-like shape and the greater the irregular shape, the weaker the coherence of the overall campaign strategy.

- The gap between the two campaigns can show us:

- the difference between strategically and non-strategically executed campaigns;

- the strategic vacuum that a weaker movement might use for learning and planning to improve its specific attributes in the future.

Figure 2: The Strategy Web Mapped: Polish Solidarity Movement vs. Chinese Pro-Democracy Movement

The main challenge for the effective application of the web strategy tool is in assessing the scores for each identified attribute. Because of a lack or limited information at a time of mapping, the scoring might be inaccurate or perceived as subjective. As with any quantification of social processes the most effective approach to scoring is to ensure that it is based on discernible facts, input from multiple sources, interviews with observers of and direct participants in these processes, and peer review by informed experts. In fact, any conflictual information and disagreements about scoring and ranking of specific attributes might be a valuable lesson by itself, revealing to movement strategists where the discrepancies and a lack of consensus around attributes exist and the need to better understand and address them.

Eventually, the added value of the strategy web is its versatility—it can be used to analyze the conflict with multiple actors where civil resistance takes place. It also produces an attractive and easy-to-interpret visualization of movement effectiveness and areas of strategic weaknesses that should be addressed and strengths that resisters can build on to advance their campaign goals.

If you decide to adopt this tool in your training and education, please let us know about your experience and/or audience reactions and lessons learned by contacting us at academicinitiative@nonviolent-conflict.org.

1. The list of online and print guides related to civil resistance, not inclusive by any means, includes in no particular order: The Checklist for Ending Tyranny; ICNC's The Path of Most Resistance; People Power Manual: Campaign Strategy Guide; Change Agency’s Campaigners' Toolkit; War Resisters International's Handbook for Nonviolent Campaigns; Beautiful Trouble; US Institute of Peace's SNAP Guide; "An Activist’s Guide to Fighting Foreign Disinformation Warfare"; The CANVAS Core Curriculum; Conflict Analysis Field Guide; and Conflict Analysis Tools.

2. I came across the web tool in the Chatham House publication, Civil Society Under Russia’s Threat: Building Resilience in Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova (2019) and immediately recognized its applicability to the civil resistance field.

Maciej Bartkowski

Dr. Maciej Bartkowski is a Senior Advisor to ICNC. He works on academic programs to support teaching, research and study on civil resistance. He is a series editor of the ICNC Monographs and ICNC Special Reports, and book editor of Recovering Nonviolent History. You can follow him @macbartkow