Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Maciej BartkowskiDecember 27, 2021

With more than 150,000 Russian troops staged along on the Ukrainian border, and also massing in Belarus and the occupied territories of Crimea and Donbas, Ukraine is facing a potential full-fledged invasion by its larger authoritarian neighbor and the occupation of a sizable swath of its territory.

U.S. and Ukrainian intelligence services report that Russian President Vladimir Putin has not made up his mind yet about the invasion. However, time is of the essence. January and February are the most convenient months for Putin to invade because land remains frozen for easier and faster movement of heavy equipment including tanks, in the event that railways, bridges and roads are blown up.

If Putin decides to launch a full-scale military invasion, it will be because he thinks that he will achieve rapid military victory over his much more powerful forces over the Ukrainian army, even if the latter receives military support from the West. If he pushes his offensive all the way to Kiev, it would also signal his belief that the current Ukrainian government would be quickly removed from power and replaced by a puppet pro-Russian regime. Alongside is his view that the majority of the Ukrainian people would passively accept the Russian invasion and occupation in the same way the majority of the population inside Donbas and Crimea did from 2014 onward. After all, Putin claims Russians and Ukrainians are the same people and have simply been separated from each other by the Ukrainian nationalist elite. According to his rhetoric, once this elite is removed from power, Ukrainians would gladly accept reunification with Russia.

To influence Putin’s calculus about the full-scale invasion, some in Ukraine and the West emphasize that Ukrainians are ready for protracted guerrilla warfare and that Ukraine could be for the Russian leader what Afghanistan became for the Soviets. However this scenario, if realized, would be equally painful for Ukrainians as it would be for Russians. After all, Afghanistan was left in ruins and hundreds of thousands of people were killed and became refugees, even if eventually they prevailed over their invaders.

Putin's assumptions are dangerous miscalculations with potentially terrible consequences for Ukrainians.

What would you do in case of a foreign armed invasion?

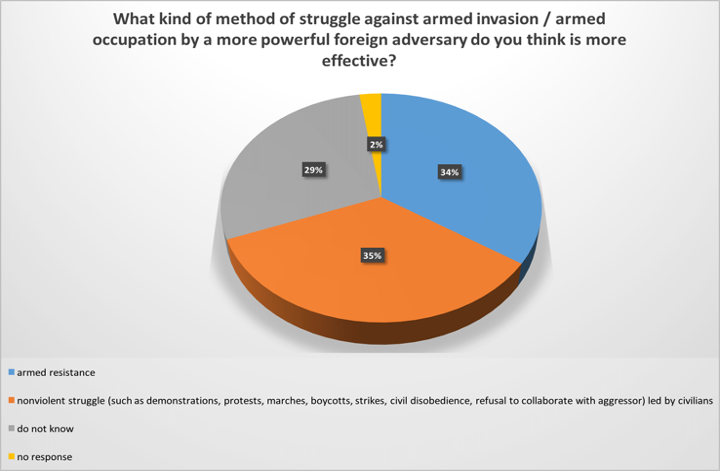

In 2015, the Kiev International Institute of Sociology (KIIS) conducted a representative national survey1 that for the first time ever assessed Ukrainians’ preferences for resistance in case of a foreign armed invasion and occupation of their country. The poll took place just after the Euromaidan revolution and the capture of Crimea and the Donbas region by Russian troops, when it could be expected that Ukrainian public opinion would be strongly in favor of defending the motherland with arms. The results, however, revealed surprisingly strong support for an alternative to an armed-defense type of resistance: civilian-led nonviolent defense. The survey showed that the most popular choice of resistance among Ukrainians was to join nonviolent resistance: 29% supported this choice of action in case of foreign armed aggression and 26% in case of occupation. In contrast, armed resistance was supported by 24% and 25% respectively. See Figure 1. Only 13% of Ukrainians would behave in the way Putin would hope in case his troops invade Ukraine—do nothing.

Figure 1

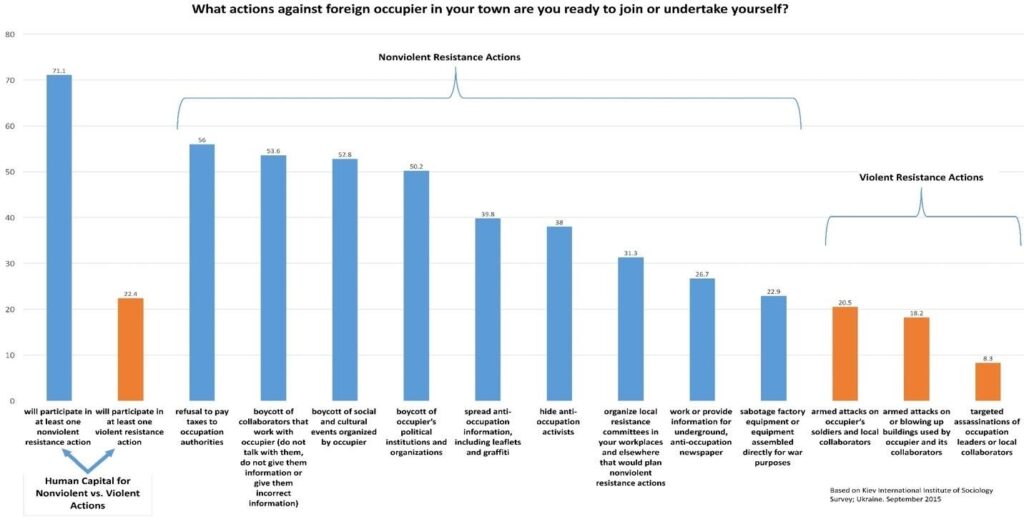

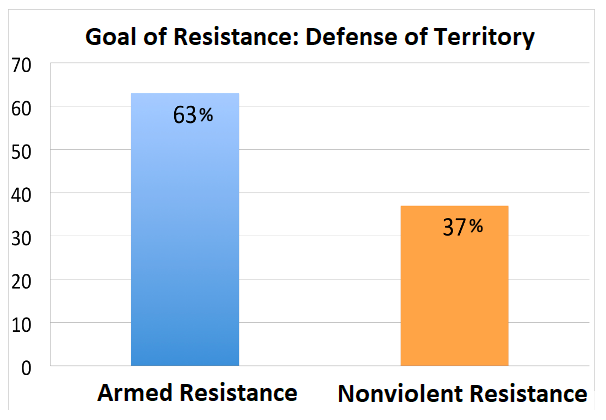

It's one thing that more respondents selected civilian-led nonviolent resistance than any other option. It's even more remarkable that more than one-third of Ukrainians thought that this alternative type of resistance could be an effective means of defending their communities against a foreign adversary with a more powerful military. See Figure 2.

Figure 2

These results, interestingly enough, correspond closely with the historical record of anti-occupational struggles. The data show that between 1900 and 2006, nonviolent struggles against occupiers succeeded 35% of the time while armed resistance succeeded 36% of the time (Chenoweth & Stephan 2011). Neither type of resistance succeeded more often than it failed, but successful and failed armed resistance lasted on average three times longer than its nonviolent counterparts; always came with a huge human and infrastructural cost for the local population (e.g. Vietnam 1960s); had much lower probability of building democracy afterwards (Algeria 1962); and destroyed or traumatized civil society (e.g. Hungary 1956) whose strength and mobilization are needed for democracy building and its sustainability. In contrast, nonviolent resistance historically can succeed much faster than armed struggle (Nepal 2004); even failed nonviolent resistance more effectively preserves the fabric of civil society to restart a fight another day (Czechoslovakia 1968) and it has much higher chances of building democracy than successful armed resistance (Poland 1980s vs. Afghanistan 1980s and 2000s).

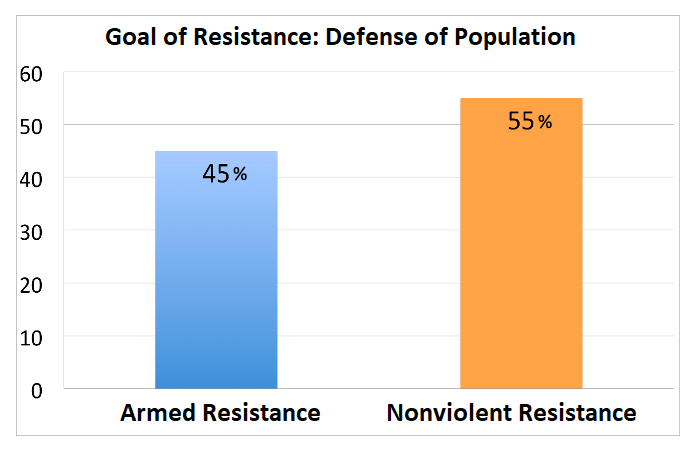

Furthermore, according to the survey, those among Ukrainians who seek to protect territory are more willing to take up arms. Those seeking to protect their families and communities would rather turn to nonviolent resistance methods. See Figures 3a and 3b. There is a seemingly intuitive understanding among Ukrainians that armed resistance would inflict terrible costs on the local population. Potentially it makes better sense to use violent resistance far away from major urban centers where nonviolent resistance against occupiers could ensue in its stead.

Figure 3a

Figure 3b

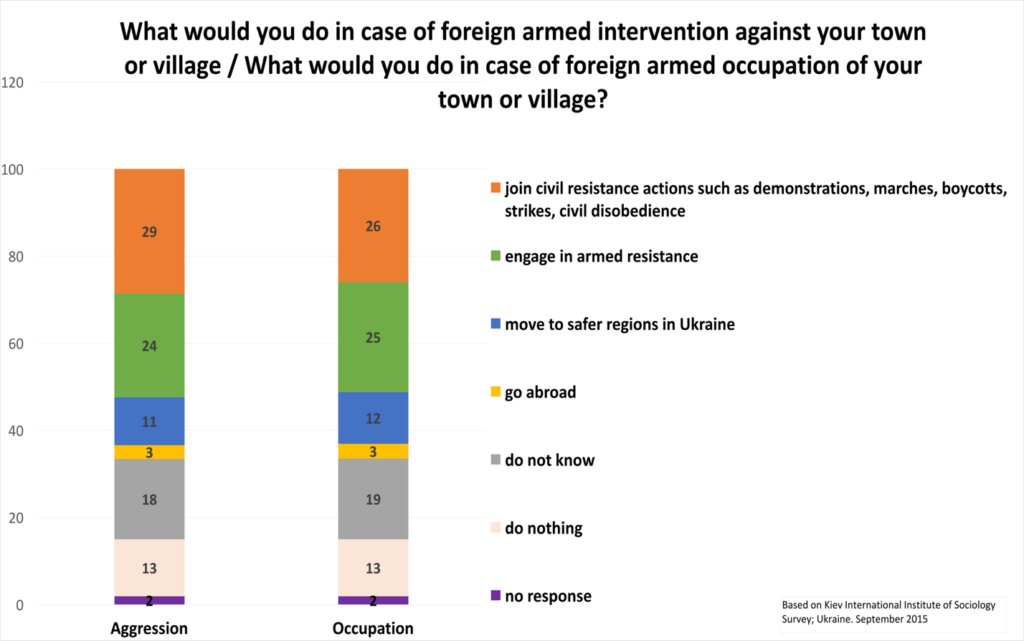

Ukrainians were also asked to choose specific types of armed and nonviolent resistance actions that they would be ready to join or undertake themselves. Clear majorities chose various nonviolent resistance methods—ranging from symbolic to disruptive to constructive resistance actions against an occupier—rather than violent insurgent actions. In essence, the results demonstrated that the human capital for civilian-based nonviolent defense among Ukrainians was more than three times larger than that for armed resistance. See Figure 4.

Figure 4

Key takeaways

So, what do these findings mean in the context of a potential military invasion and occupation of Ukraine by Russian forces?

A few important takeaways include:

• Putin’s belief that Ukrainians would rather go home and do nothing in the face of military aggression may be his biggest and politically most costly miscalculation in the event that he decides to launch a full-scale invasion and occupation of large parts of Ukraine;

• Ukrainians do not necessarily embrace the idea of an Afghan scenario in which an armed guerrilla movement wages warfare against invaders that is equally destructive for the local population. Instead, they view unarmed defense and resistance of the civilian population not only as a plausible alternative that can better protect the population and minimize human costs of violent conflict but also as a way to achieve victory against a militarily stronger opponent;

• Successful anti-occupation struggles have always been a whole-of-nation endeavor. Unarmed resistance has greater mobilization potential for a whole society to participate in diverse actions of defiance and noncooperation than armed resistance;

• Ukrainians show a surprising level of support for the type of resistance that neither Ukrainian policymakers nor their Western backers have considered in their defense planning: mass nonviolent resistance actions against a formidable military invader. This human potential for nonviolent resistance remains unfortunately untapped in the Ukrainian national defense strategy;

• How Ukrainians defend their country against a more militarily powerful adversary will determine Ukraine's future, including the survival of its nascent democracy. A protracted armed struggle often privileges a strongman to the detriment of democratic change. Ukraine’s activated population can be tapped not only to effectively resist foreign aggression by means other than arms but also to prevent an internal coup and emergence of a domestic military dictatorship—possibly closely allied with Russia—from overtaking the country's young democracy.

A 2015 Lithuanian civilian-based defense manual, available both in English and Lithuanian.

• Civilian-based defense is neither an uncommon historical practice nor an alien concept to contemporary national defense strategies. Such resistance was a driving force behind various liberation struggles including: American colonists' resistance against the British; Hungarians' mobilization against the Austrian Habsburg monarchy; Polish civil resistance against partitioning empires, including Tsarist Russia in late 19th century; and pro-independence movements in Egypt, India, Bangladesh, Ghana, Estonia, among others. Nowadays, efforts are underway to integrate comprehensive nonviolent civilian-based defense in the Baltic states. This is highlighted in the specific recommendations for nonviolent defense strategies put forward by a respected U.S.-based security think tank. And Lithuania has been at the forefront of these implementation efforts when in 2016 the government adopted a new military strategy for "reliable deterrence [that requires preparing citizens for] unarmed civil resistance, [including] fostering their will and resilience to information attacks, as well as ability to engage in a total resistance…of the whole nation". The Lithuanian Ministry of Defense issued two preparedness manuals on the "modes and principles of civil resistance” in its national defense.

---------------------------

1 The survey results were first described and presented in English in the coauthored article "To Kill or Not to Kill: Ukrainians Opt for Nonviolent Civil Resistance" published in Political Violence @ Glance.

Maciej Bartkowski

Dr. Maciej Bartkowski is a Senior Advisor to ICNC. He works on academic programs to support teaching, research and study on civil resistance. He is a series editor of the ICNC Monographs and ICNC Special Reports, and book editor of Recovering Nonviolent History. You can follow him @macbartkow