Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Sonja StojadinovicMay 12, 2021

Last November, Montenegrin politician Dritan Abazovic publicly commented that female politicians and women in general should stay out of negotiations to form a new government so that they are not overburdened with complicated political matters. The statement provoked major backlash in Montenegro, and three female activists, known as Ljeposava, Jeka, and Joka, decided it was time for women to take things into their own hands.

They created Facebook, Instagram, and Twitter pages called Vala, Ljeposava (“Let me tell you, Ljeposava”), a nod to a popular 1980s TV series in Yugoslavia, Djekna jos nije umrla (“Djekna has not died yet”). Through humorous and sarcastic memes that revive the main characters from the series, Ljeposava dramatize injustices committed against women in Montenegro, but its influence has spread to other former Yugoslav countries. The explosion of user comments within the first few weeks indicated that the online campaign became popular very quickly throughout the former Yugoslavia countries.

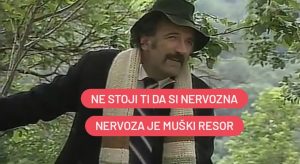

Sarcastic meme from the Ljeposava Facebook page: "It does not suit you to be nervous, being nervous is [for men]."

Testimonies as resistance

Ljeposava is best known for collecting and amplifying women’s testimonies of mistreatment as a way to pressure politicians to take their grievances seriously. Women talked about being denied anesthesia during the process of childbirth. They spoke of being subject to offensive and misogynist comments during routine gynecological check-ups performed both by female and male doctors. Some shared that they were accused of being prostitutes only because they came with vaginal inflammation. Others were denied treatment for polycystic ovaries syndrome; the doctors said that the condition would be “cured” with pregnancy.

These stories from women all over the Balkan region caused public outcry. Hundreds of women have shared their traumatic experiences while under medical care via the online campaign led by Ljeposava. Some said these traumas contributed to the decision not to have another child—out of fear of further inhumane treatment and possible medical complications.

Bridging the online-offline divide

In my March 2021 interview with Jeka, Joka, and Ljeposava (referred to herein as Ljeposava), they humbly recognized that the campaign only amplifies what women throughout the region were already thinking. “We started a conversation about the participation of women in politics—or the lack of it—and that is how our campaign started, but we also tackled topics such as care work and the patriarchal and misogynist behavior in social and family circles…” they shared.

The campaign has bridged the online-offline divide by amplifying lived experiences onto online platforms. “We encourage women to complain whenever they are mistreated. It’s instrumental that we keep demanding accountability, keep the pressure up—otherwise, nothing will change,” noted Ljeposava.

Realizing the scope of the problem, Ljeposava and other activists decided to take the conversation one step further and address the authorities directly, just this past March. They promptly received an answer from the Montenegrin Ministry of Health, as well as a public statement addressing the issue. While the minister showed concern and eagerness to solve the problem, other officials, such as the Head of OB-GYN Clinics, tried to bury it by subtly accusing the women of lying.

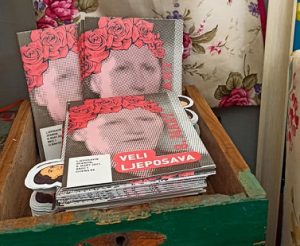

Fanzine copies at the Kreativna zona (Creative zone) bookstore in Podgorica, Montenegro. Source: Ljeposava Facebook page.

The fanzine as a popularizing tool

An additional nonviolent action that the Ljeposava campaign launched this year is their fanzine—a publication created by amateur journalists—to inform and persuade the public about the condition of women. The first issue celebrated International Women’s Day (March 8). Joining other expressive tactics using the medium of human language, such as newspapers and journals, the fanzine served as a foundation for connecting and collaborating with other feminist movements in the region, which Ljeposava believe is crucial for fighting this fight.

The first Veli, Ljeposava was printed in 230 copies, some of which were mailed to the four newly appointed women ministers of the Montenegrin government. The rest were sold in Podgorica (Montenegro) and Belgrade (Serbia) with proceeds going to various causes.

The fanzine was designed as an old-fashioned women’s magazine, with a horoscope, a “steal the look” feature, and advice sections. Ljeposava used these stereotypical forms and made them subversive by addressing issues such as labor rights, activism, and care work. The editors want the readers to have fun, enjoy some poetry written by women, but also to make the readers think critically. Some of the latest feminist theories are curated, translated, and printed on the back of poster inserts.

The fanzine has been a way for the Ljeposava campaign to “keep it casual” with their followers. It has also helped popularize the struggle for better conditions for women in the region and laid the foundation for acts of solidarity.

Building alliances for solidarity

Ljeposava didn’t have an elaborate plan for launching the campaign; it remains “very much a work in progress,” according to the activists. They simply saw a need to create space for exchange of information and perspectives on political topics.

Currently, the campaign is building on spontaneous acts of solidarity to expand their allies, including journalists who can regularly highlight the condition of women in more traditional media outlets. Other acts of support and solidarity have included:

- Well-known Serbian poet Maja Solar enthusiastically opted to be a part of the campaign by letting Ljeposava print one of her poems.

- The printing office printed a dozen copies more of the fanzine than they ordered and paid for.

- A woman from the store where the fanzine was originally sold went above and beyond to get the fanzine to everyone who requested it; “we even got a photo of a copy that reached Paris!” Ljeposava exclaimed during my interview.

- The Beopolis bookstore in Belgrade volunteered to mail fanzine orders to other cities in Serbia, which helped to decentralize the spread of the fanzine during the pandemic.

These are just a few examples of solidarity, coming from people who don’t even know who stands behind the Ljeposava campaign. It demonstrates the unifying power of an idea that reflects the experience, hardships, and voice of a significant portion of society. It gives us hope that we can do much more—and we will.

Sonja Stojadinovic

Sonja Stojadinovic is an MA student in Southeast European Studies at the University of Graz, Austria. She holds bachelor and master degrees in political science and international relations, both obtained on the Faculty of Law, Skopje, University of St. Cyril and Methodius, Republic of North Macedonia. She is also an activist and well-known columnist for North Macedonian daily newspapers and regional political web sites.

Read More