Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Brian MartinJanuary 20, 2022

Read also: "What Soldiers and Police Should Do at a Protest (Series Part II)"

This blog post is also available in Thai here.

If you are called out to deal with protesters, you need to understand their methods and motivations.

You’re a soldier or police officer who’s been asked to control and possibly shut down a public protest. You’ve been told the protesters are threatening public safety and national security. However, when you encounter them, things are not so clear. There are hundreds or thousands of people and they are not being violent. They say they are standing up for your country’s values.

Later, you see a few people throw rocks and smash windows. Do they represent the protesting group? Are they trying to provoke you to be heavy-handed?

Around the world, more and more popular movements are protesting without physical violence. You may have to make quick on-the-spot decisions about what to do, so it’s important to know something about what these protesters are doing and why they are behaving the way they do. Here is some basic information that’s worth knowing (based on my recent Security & Defence Quarterly article, “Military-protester relations: Insights from nonviolence research”).

What is nonviolent action?

Nonviolent action is a way that people try to promote social, economic, and political change. There is a wide array of methods of nonviolent action, including rallies, marches, strikes, boycotts and sit-ins. These sorts of methods do not involve physical violence or the threat of violence against opponents. Nonviolent action is sometimes used by itself, and sometimes is used in conjunction with other methods of making change, such as election campaigns, the court system, and negotiations.

Other names for nonviolent action

Civil resistance is used by some scholars and activists.

People power is sometimes used by journalists.

Satyagraha is Gandhi’s term, literally “truth force.”

How does nonviolent action work?

Nonviolent action is a form of political action aimed at expressing views and applying pressure. For example, strikes and boycotts can apply economic force and sometimes coerce change. However, the idea is to respect the dignity of the opponent by not physically harming or threatening them. Because of this, the door is opened to dialogue and negotiation.

In addition, because people engaged in nonviolent action are often exercising their widely recognized human rights, and do not present a physical threat, if police or soldiers physically attack nonviolent protesters, some observers will think this is wrong. When this happens, it can lead to greater support for the protesters, a process called “political jiu-jitsu.”

In warfare, each side uses violent force to try to defeat the enemy. But when one side applies only nonviolent pressure, using violent force may backfire.

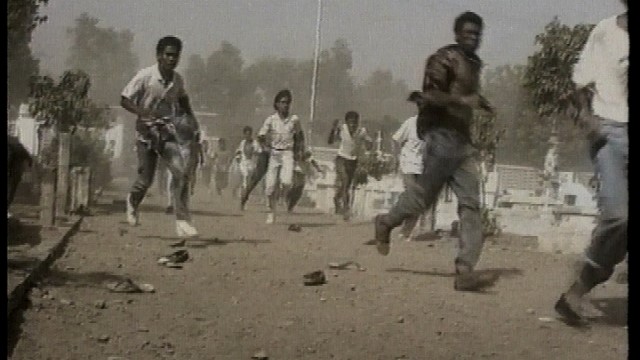

(A still from ABC Foreign Correspondent on Dili Massacre - Santa, available publicly here)

The Dili massacre

In 1991, hundreds of East Timorese joined a funeral procession that also served as a protest against the Indonesian occupation. As the marchers entered Santa Cruz cemetery, Indonesian troops—who had surrounded them the whole way—opened fire, killing many East Timorese. This massacre was witnessed by Western journalists accompanying the march, and captured with photos and video footage. After the journalists returned home, their testimony, and a film made with the video footage, reinvigorated the international solidarity movement in support of East Timorese independence.

The massacre backfired against the Indonesian government. Rather than squashing the independence movement, the massacre increased international support for the movement and discredited the Indonesian government and military. East Timor gained independence a decade later.

What’s going on with the protesters?

Returning to the opening example in this article, there’s a protest, and most of those attending are peaceful. But a few are flinging stones at police, throwing bricks through shop windows, throwing punches at police, or even hurling Molotov cocktails. What’s going on?

When just a few protesters use violence, there are several possible reasons.

- Some individuals start out being peaceful but become angry and lash out. This is sometimes because they are provoked by authorities, for example by having their rights violated and being subject to arbitrary and/or disproportionate use of force. In a well-planned nonviolent protest, there will be training beforehand to help protesters remain nonviolent even if they are assaulted. In these cases, the organizers want everyone to avoid violence. However, the training might be too brief, or people who didn’t attend the training might show up to the protest. In addition, some actions are organized very quickly on social media, and lots of those attending have had no training in nonviolent action, and perhaps have never been in a protest before.

- Another possibility is that some activists reject nonviolent discipline and want to break windows or clash with authorities. In planning for actions, there can be debate over tactics. Even when most of those involved are committed to nonviolent discipline, others argue instead for “diversity of tactics.” Usually this means using violence against property (rather than people) but sometimes it involves throwing things at police and troops.

- There may be agents provocateurs among the protesters. These are often undercover police or people paid by the government to be violent and therefore discredit protesters.

Unarmed people observe a Soviet tank go by during the occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1968 (Credit: Wikipedia/František Dostál, CC BY-SA 4.0, unedited).

Invasion of Czechoslovakia

In 1968, the Soviet government ordered an invasion of Czechoslovakia. Half a million Warsaw Pact troops entered the country. The troops had been told they were being stationed there to stop a capitalist takeover. When they arrived, there was no armed resistance. Instead, young Czechoslovak civilians protested against the invasion. They tried to talk to Russian soldiers, telling them that they too were socialists and supported a reformed version of socialism. Many of the invading soldiers became “unreliable” — they questioned the orders they were given — and were rotated out of the country.

Although a puppet government was eventually installed in Czechoslovakia, the invasion was disastrous for the Soviet government. It discredited state socialism, causing splits in Communist parties worldwide. The soldiers who questioned their orders were vindicated by history.

In my next post, I will outline what police and other security forces can do when they encounter nonviolent protesters.

Brian Martin

Brian Martin is Emeritus Professor of Social Sciences at the University of Wollongong, Australia. He has been researching nonviolent action since the late 1970s, with a special interest in strategies for social movements and tactics against injustice. He is the author of 21 books and over 200 articles on nonviolence, dissent, scientific controversies, democracy, education and other topics.

Read More