Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Amos OluwatoyeApril 06, 2023

Another presidential election has come and gone in Nigeria, leaving political parties, civil society and a disgruntled electorate in disarray over all the alleged irregularities that were recorded. Bola Tinubu was announced as the president-elect under the ruling party, the All Progressives Congress, by the Independent National Electoral Commission (INEC)—a body largely viewed as incompetent. Aggrieved parties and ordinary citizens have been demanding transparent judgment or re-election, and they've been doing so through nonviolent actions that draw heavily on creativity and humor.

Humor has become a major force in challenging the incompetence of the electoral body to conduct a free and fair election, and overall Nigerian "politics-as-usual". Humor as resistance is the use of jokes, satire and other tools of comedy to dramatize injustices and expose an adversary’s illegitimacy, with the goal of pressuring for more democratic practices. Over the past few months, comedians and social media content creators in Nigeria have utilized the creative power of humor to change the political status quo, and this article examines how.

The Emilokan syndrome

Bola Tinubu. Credit: Chatham House/Wikipedia.

A few months before the election, Tinubu, the presidential flag bearer of the All Progressives Congress, declared in public that it was his turn to become president because of his past contributions to the party. He used the word “emilokan”, which is Yoruba for "it's my turn". He further asserted, “Yoruba Lokan”, meaning “It’s the Yoruba tribe’s turn to produce the next president.”

What has been dubbed the Emilokan syndrome is an illness that affects a select group of narcissistic politicians in Nigeria who think they are entitled to something. They argue that they have previously served as “kingmakers” by choosing the nation's rulers, so they are now in a position to be repaid for the favor. This undemocratic political culture has given the powerful few disproportionate control of the nation and its resources.

Commonwealth Observer Group Nigeria General Election, February 25, 2023 Credit:. Commonwealth Flickr (CC BY NC 2.0, unedited).

The Emilokan syndrome was transformed into a musical satire by the Pyrates Confraternity, commonly known as the National Association of Seadogs, in a hit song entitled "Baba wey no well, him dey shout emilokan." (A man that is ill is shouting 'it's my turn'). Tinubu became the target of the joke: "Hand dey shake, leg dey shake, baba wey no well him dey shout Emi Lokan." This loosely translates as: "With an unstable hand and leg, a man with poor health is shouting that it's his turn to be Nigeria's president."

The group sang and danced in a one-minute video (watch below) that went viral on social media over the past few months. Comedy skit makers and video editors remixed and disseminated the video to satirize the idea that Nigeria is the property of a few power-drunk politicians and tribal bigots.

The “how” of humor and the Obi-dient movement

One of the reasons we laugh, according to humor theorist Henri Bergson, is to feel superior in an authoritarian setting, where power dynamics frequently favor the privileged few. This is only the tip of the iceberg. In civil resistance terminology, we might identify humor as a source of “power within” and even an enabler of more deep-seated changes in society.

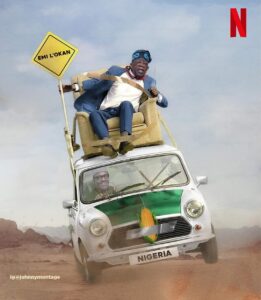

"Nigerians who's your Next President?? Comment below," writes Johnny Montage on his Instagram account. Click image to view full post. Credit: Johnny Montage.

The example of the Obi-dient movement gives us insights on how humor not only eases political tension—even if just marginally—but also creates channels for opening up political space for parallel institutions to emerge. Young Nigerians involved in the Obi-dient movement (whose members are also part of the Labour Party) contributed to the emergence of a third major political party. Nigeria hasn’t had a significant third party in politics since the start of the fourth republic in 1999.

The movement’s name comes from Peter Obi, a presidential candidate from the historically disenfranchised Igbo group in Nigeria’s southeast. The movement organized peace walks in conjunction with humorous online campaigns to play up the Emilokan syndrome. By providing spaces for ordinary Nigerians to laugh at a toxic political trend, the movement helped undermine the credibility of, and thus demobilize the ruling party. In a word, with the ruling party as the butt of the joke, fear changes sides (and ruling elites in Nigeria will surely be wary of the words they use in public statements from now on...).

“This country suppose dey Netflix…”

“Na the people wey get Nigeria be this. This country suppose dey Netflix…” meaning roughly, “These are the owners of Nigeria. This country must think it's on on Netflix.” Click to view full post on Instagram Johnny Montage.

A graphic ridiculing the culture of political succession in Nigeria, created by John Okoli, a visual artist, went viral during election season. The image of the president (Buhari) is seen driving a car and the controversially elected president (Tinubu) on top holding a signpost with the words ‘Emi Lokan’ written on it.

When I asked John what inspired him, he wrote, “I’m a Nigerian. I have to be able to tell the Nigerian story the best way I can.” The text posted with the image on his Instagram page says: “Na the people wey get Nigeria be this. This country suppose dey Netflix…” meaning roughly, “These are the owners of Nigeria. This country must think it's on Netflix.” It gives the impression that the presidential election and the alleged shenanigans that followed were all scripted by the president and the ruling party to favor themselves.

When political jokes are no joke

Anywhere people are mobilizing against the government, the possibility of repression of some kind is likely, if not certain. Around the world, political jokes are no joke for authoritarian regimes when the regime’s power to control the people starts to fissure.

In India, authorities crack down on comedians for mocking the political establishment. Comedians have been harassed, detained and abducted for criticizing or propagating criticism of the state through humor in Zimbabwe. In Nigeria in the 2010s, Buhari’s government understood the impact that political jokes made in exposing the incompetency of Goodluck Jonathan’s administration. Nigeria’s secret police, the Department of State Services (DSS), in June 2022 arrested a comedian and vlogger, Chukwu Michael Emeka, who uses comedy skits to talk about poor governance and insecurity, issues affecting many Nigerians. He was later granted bail and released.

Nevertheless, political jokes that address society’s pressing issues are precursors to, and sometimes even enablers of other nonviolent means to achieve political change. While some people see comedy only as an opportunity to “crack their ribs” (in Nigeria this expression means to laugh), it can and does achieve much greater goals. Humor opens up the possibility for citizens to withdraw their support from a ruling party and pressure for more democratic practices.

Amos Oluwatoye

Amos Oluwatoye is Research Director with Building Blocks for Peace Foundation and Research Volunteer with Metta Center for Nonviolence. An ICNC alum, he is actively involved in research, community, and international development projects focused on peacebuilding, nonviolent movements for societal change, political violence, public policy and international development.

Read More