Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Amber FrenchJanuary 04, 2023

“Nonviolence is naïve. Humans are violent by nature.”

“Violence is needed to confront violent adversaries.”

“Nonviolent resistance undermines institutional means of change.”

If you are an advocate of nonviolent resistance as a constructive form of political action to combat injustice, it’s likely you’ve encountered comments like these while discussing your work with others. Sometimes our interlocutors are unaware of research that contradicts their views; some may also inadvertently echo misinformation that has been intentionally propagated to try to discredit popular movements for democracy and human rights.

Views such as the above are understandable in light of society’s socialization and ongoing elevation of violence in news, education and entertainment media. It can be frustrating to have to respond to such views on a regular basis. But if the other person is engaging in good faith, responding can also be an opportunity to deepen the conversation, learn about their perspective, and share our own.

In this article, I dig deeper into some widespread assumptions about nonviolent resistance, in the spirit of reinforcing the capacity of advocates of the effectiveness of civil resistance to steer conversations toward higher ground.

Assumption #1: Man is violent by nature.

Reality: Nonviolent resistance is the default method of political action among ordinary people worldwide today.

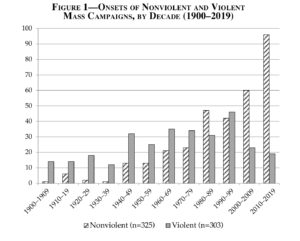

Click to enlarge. Source: Chenoweth, Erica. “Future of Nonviolent Resistance”, Journal of Democracy 31 (3), July 2020, pp. 69-84.

Many people believe that humans are violent by nature. In reality, people have free will, so things aren't so black and white. Plus, it doesn’t help that violence induces fear, thus it retains our attention despites its infrequency in relative terms.

But in reality, we have three courses of action when facing an injustice: we either fight back violently, not fight at all (do nothing or flee), or respond using nonviolent action. In a 2020 study based on a robust data set of campaigns, political scientist Erica Chenoweth found that from 2010 to 2019, the number of new nonviolent campaigns seeking political transitions outnumbered the number of new violent campaigns—by a factor of five.

Violent insurgencies like guerrilla movements, while still not a vestige of the past, have become increasingly rare since the mid-20th century. Instead, nonviolent resistance has become the default method of political action among ordinary people worldwide today (see graph).

Assumption #2: Violence is a necessity to combat injustice.

Reality: Violence is one prism for understanding the world, but it is not the only one.

“Violence is a necessity” is a simple concept to grasp, so many people just don’t look further. Besides, most of the time, we are not presented with any competing theories in history books, at church, in mainstream media and so on. The way we interpret the society we live in and what’s happening in the world is a direct reflection of our own societal, family and personal values.

If your interlocutor thinks violence is a necessity, ask him whether he has ever read about a nonviolent movement before—something written by a scholar of nonviolent movements or a nonviolent movement veteran (this blog contains 250+ such articles). Because we usually find what we're looking for: if we wish to see the world through the prism of violence, violence is what we find. If we want to add a different perspective to our understanding of the world, learning about nonviolent resistance can help us achieve this. And besides, there is no shortage of free online resources in dozens of languages… you simply have to look.

Assumption #3: Nonviolent resistance undermines institutional means of change.

Reality: Nonviolent resistance is a viable option when institutional change is not working and injustice persists in a society.

Nonviolent resistance is political action that takes place outside of institutions (characteristically, but not exclusively, “in the streets”). It’s not classic institutional politics, for sure. But successful nonviolent resisters act, in concert, where they can potentially have a direct impact on public opinion: in the public sphere. Then, once they gain political leverage and credibility among the broader population, successful resisters often return to the negotiating table and pursue change within institutions. In other words, many movements engage in nonviolent action in ways that ultimately strengthen institutions and get them to work. If an institution has been corrupted, sometimes outside pressure is needed to get it to return to its mandated purpose.

The goal of nonviolent resistance is construction: obtaining human rights and justice where suffering prevails, achieving freedom for the oppressed, setting a country on the path toward democratic change, and so on. So, in reality, the choice isn’t between nonviolent resistance and institutions; it’s between nonviolent resistance and accepting injustice.

Historically, the impact of nonviolent resistance has often been complementary to democracy, because both methods share means and ends: political change, without violence, through civic mobilization. Violence and injustice are the antithesis to this. The real question is: Is my choice of method more likely to lead to civil war or to a path toward democratic change?

An established body of research finds that nonviolent action supports democratic development. There are also circumstances where it can be used to undermine institutions (for example, challenging election results in a free and fair election with no evidence of fraud). However, such uses over history tend to be more the exception than the rule. In many cases, movements are demanding that institutions live up to their legal mandate and purpose rather than attempting to impose an anti-democratic outcome on them (see Jonathan Pinckney’s research for more on this).

___

While it is easy to dismiss common assumptions about nonviolent resistance that may come up from time to time in our discussions with others, we must be reminded that letting some assumptions go unchallenged does not do justice (pun intended) to the decades of sound social science research and the practitioner-refined corpus that our field boasts. For example, the false dichotomy of “civil resistance vs. institutions” is at the origin of conspiracy theories that dictatorships initiate to undermine the credibility of nonviolent movements for rights, justice and freedom. It is always worth engaging an interlocutor in a meaningful conversation to exchange views and suggest new perspectives.

Special acknowledgment goes to Hardy Merriman for providing substantive input to this post.

Amber French

Amber French is Senior Editorial Advisor at ICNC, Managing Editor of the Minds of the Movement blog (est. June 2017) and Project Co-Lead of REACT (Research-in-Action) focusing on the power of activist writing. Currently based in Paris, France, she continues to develop thought leadership on civil resistance in French.

Read More