Minds of the Movement

An ICNC blog on the people and power of civil resistance

by Amber French and Olga SagaidakJune 30, 2022

“When you’re doing something, only in the future can you understand for sure what the real goal was. For now, we see the project as documentation of crimes being committed, of war being waged, of normal Ukrainians’ lives, their cities… It’s about building an enormous database of Ukrainian cultural values… And it’s not just Ukrainian heritage, it’s European heritage.”

-Olga Sagaidak, cultural activist, prominent figure in the Ukrainian art world

This article is also available in Ukrainian.

In my first post, I shared inspiring stories about unarmed civilian protection of museums in war-torn Ukraine. I also analyzed the Ukrainian art world's international call to boycott Russian cultural objects and artists close to Putin. In this post, I zoom in on what I’ve dubbed elsewhere as “documentary resistance”, drawing from a recent interview I conducted in Paris with Ukrainian cultural activist, Olga Sagaidak.

Documentary resistance is when oppressed people record their aggressor’s unjust or illegal acts using a variety of archiving techniques. Those people can disseminate the evidence in attempt to make the injustice backfire against the aggressor and/or to secure justice and reparations in a post-conflict trial.

A rather inconspicuous nonviolent tactic, traditional documentary resistance catalogues acts of genocide and other war crimes committed by authoritarian leaders. Interestingly, I learned during my interview with Olga that the Ukrainian art world is documenting a less-known yet very frequent consequence of war: destruction and pillaging of art at the hands of occupying soldiers.

The stakes of collecting and disseminating documentation

Click to expand. St. George's Church, built in 1873 in Kyiv, was damaged by Russian shelling on March 7, 2022. Credit: Postcards from Ukraine project by the Ukrainian Institute.

Crimean Tatars and other groups in Ukraine began engaging in traditional documentary resistance—that is, of Russians’ war crimes—eight years ago when the Russians took Donbass and Crimea. Speaking with Olga at the Ukrainian Cultural Center in Paris last spring, I am not surprised to learn that many of the activists involved were imprisoned and tortured for their actions.

What is interesting about cultural documentary resistance, in contrast to traditional, is that it is less immediately threatening to an occupier while still serving as an effective communication and leverage tool for anti-occupation movements.

Fast-forward to February 24 this year: As the bombs began to fall on Ukraine’s eastern cities, the Ukrainian Institute in Kyiv began collecting information in an enormous, shared spreadsheet. Each row is devoted to a Ukrainian cultural site or museum collection that was destroyed or pillaged in the war. On April 26 when I interviewed Olga, there were 150 rows. As of June 30, this has increased to more than 350 rows.

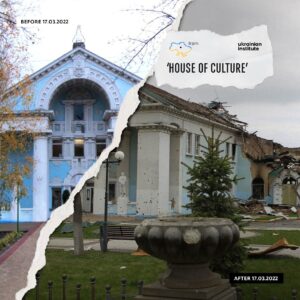

Click to expand. The House of Culture, built in 1954 in Kyiv, sustained damage by the Russian army on March 17, 2022. Credit: Postcards from Ukraine by the Ukrainian Institute.

The Ukrainian Institute works with a network of photographers and ordinary people who live in proximity to cultural sites throughout Ukraine to document this destruction. The network sends the Institute photos, news articles, and details such as date and location of the damage, the type of damage, and the party/parties responsible if known.

My interviewee’s recent role as Representative of the Ukrainian Institute in France has been organizing regular exhibits to display the collected photography and video footage (as well as protest art). I attended one such exhibit at the Ukrainian Cultural Center in Paris, which is one of several venues hosting her projects.

The spreadsheet itself is not designed for wide distribution. However, the data are fueling the Ukrainian Institute’s “Postcards from Ukraine” project, which circulates postcards that juxtapose “before” and “after” photos of cultural sites that were bombed. The imagery in simple yet compelling (see images above).

Truth-telling as resistance

The wide range of digital tools at our disposal today make both traditional and cultural documentary resistance highly accessible tactics for nonviolent movements worldwide. Smart phones, social media platforms, and cloud technology to store mass amounts of media are all documentary resisters’ best friends (though they must take digital security measures, of course). And although documentation is not as attention-grabbing as marches and protests, it is absolutely still resistance. How?

Truth-telling helps level the playing field between victims on the one hand, and on the other, their aggressors, for whom obscuring the truth is a primary objective—especially during wartime. We see the ends to which Putin’s regime will go to control the Russian narrative about the war, for fear of losing domestic political support. And in the case of the Postcards from Ukraine initiative, a picture is worth a thousand words...

Cultural documentary resistance enables Ukrainians to gain leverage over the dominant Russian narrative of the war. That leverage—if not [yet] effective at putting an end to the war—is already enabling Ukrainians to set the record straight about the war for the rest of the world and for future generations. More important, Ukrainians are setting the record straight for Russians, and this is key for weaking Putin's domestic support.

Shifting the narrative is already helping to set in motion decisive actions in Ukraine's favor. The international boycott of Russian cultural products and Russian artists close to Putin is in full cascade, not to mention Ukraine recently got on the fast track to EU candidature.

The battlefield advantage

Ukrainians are navigating an asymmetrical battlefield in favor of the Russian forces. There is currently no political framework in place for providing international protection of cultural heritage in countries under occupation. It’s far too late now to export collections to be hosted at foreign museums.

Facing seemingly insurmountable obstacles, I find it truly courageous that the Ukrainian art world is taking bold actions to preserve their country's immense cultural heritage, both in-country and from afar. After all, as Olga aptly puts it, "This war is a war of cultures". Putin's only language is violence; Ukrainians have been fluent in the language of nonviolent resistance for decades. By putting culture in a key position of the anti-occupation struggle, Ukrainians can and are nudging the conflict to where they can have a battlefield advantage.

Amber French

Amber French is Senior Editorial Advisor at ICNC, Managing Editor of the Minds of the Movement blog (est. June 2017) and Project Co-Lead of REACT (Research-in-Action) focusing on the power of activist writing. Currently based in Paris, France, she continues to develop thought leadership on civil resistance in French.

Read More

Olga Sagaidak

Olga Sagaidak is a Ukrainian cultural activist, art manager, and curator. Since the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022, she has been representing the Ukrainian Institute in France. As a cultural activist, she initiated and now curates for the Ukrainian Spring project (Printemps ukrainien) at the Ukrainian Cultural Center in Paris. Previously, Olga co-founded the charitable foundation The Depths of Art (Dofa Fund).

Read More