Civil Resistance

Civil resistance is a powerful way for people to fight for their rights, freedom, and justice—without the use of violence.

When people wage civil resistance, they use tactics such as strikes, boycotts, mass protests, and many other nonviolent actions to withdraw their cooperation from an oppressive system.

Throughout history and in the present day, civil resistance movements have forced change to happen, even against powerful opponents who are willing to use violence. They disrupt business as usual, shift the behavior and loyalties of a system’s defenders, and cause bystanders to side with the movement. In the face of widespread nonviolent defiance—and the social, economic, and political pressure that it creates—an oppressive system becomes too costly to maintain and ultimately unsustainable.

Throughout history and in the present day, civil resistance movements have forced change to happen, even against powerful opponents who are willing to use violence. They disrupt business as usual, shift the behavior and loyalties of a system’s defenders, and cause bystanders to side with the movement. In the face of widespread nonviolent defiance—and the social, economic, and political pressure that it creates—an oppressive system becomes too costly to maintain and ultimately unsustainable.

Many civil resistance campaigns and movements have created these dynamics and changed history as a result.

Where has Civil Resistance Been Used?

Civil resistance has been waged in hundreds of societies and cultures around the world. It has been used for diverse purposes throughout history, such as:

- Holding governments, corporations and other non-state actors accountable

- Achieving women’s rights, minority rights, indigenous rights, labor rights, and democratic rights.

- Anti-corruption and transparency campaigns

- Self-determination struggles

- Resisting foreign occupation

- Campaigns for public and community safety and reducing deadly violence in conflict zones

- Environmental sustainability and conservation

- Land reform

- Many other causes

Here are specific examples:

- The British gave up their occupation of India after a decades-long nonviolent struggle by the Indian population led by Mohandas Gandhi.

- The Danes, Norwegians and other peoples in Europe used civil resistance against Nazi invasion during World War II, raising the costs to Germany of its occupation of these nations, helping to strengthen the spirit and cohesion of their people, and saving the lives of thousands of Jews in Berlin to Copenhagen to Paris and elsewhere.

- Labor movements around the world have consistently used tactics of civil resistance to win concessions for workers throughout the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

- African Americans used civil resistance in their struggle to dissolve segregation in the United States in the 1950s and 1960s.

- Polish workers used factory-occupation strikes in 1980 to win the right to organize a free trade union, which was a major victory in a communist country at a time when tens of thousands of Soviet soldiers were stationed there.

- The Filipino dictator Ferdinand Marcos and the Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet were brought down by nonviolent movements in the 1980s.

- The anti-apartheid movement in South Africa employed boycotts and other nonviolent sanctions for decades. Nonviolent methods superseded violence in the 1980s to become the driving force that weakened the white-dominated government, forcing it to negotiate a transition.

- In 1989 thousands of Chinese mobilized in support of democracy and occupied Tiananmen Square in Beijing—but the movement was suppressed when hardliners in the government took control and ordered violent repression.

- In 1989-1990, Eastern Europeans and Mongolians used civilian-based protests to put massive pressure on communist governments, liquidating their hold on power.

- After a failed armed insurgency in the mid-late 1970s, East Timorese turned to nonviolent forms of struggle to resist Indonesian occupation of their country. Despite atrocities committed by the Indonesian military, years of a media blackout, and severe repression, successful mass-based civil resistance among East Timorese drew allies from within Indonesia, catalyzed international exposure and pressure for the East Timorese cause, and increasing the costs of Indonesian repression and occupation, which led to an independence referendum in 1999.

- In 2000, Serbs ousted Slobodan Milosevic, after a nonviolent movement helped co-opt the police and military, thereby dividing his base of support.

- In 2002, citizens in Madagascar organized nonviolently to enforce their presidential election results.

- In 2003, Georgians used nonviolent action to expose fraud and enforce election results in their country, and in 2004, Ukrainians did the same.

- In 2005, vast protests in Lebanon brought an end to Syrian military control.

- In 2006, Nepalis used nonviolent methods to restore democratic rule to their country.

- The uprising in Burma in 2007, known as the Saffron revolution, was initiated by Buddhist monks and joined by students, women and political activists. It was subjected to a brutal crackdown. However, three years later, the military began embarking on an unprecedented democratic transition that brought to power Nobel Laureate Aung San Suu Kyi and her political party. The role the Saffron Revolution played in catalyzing this political transition remains up for debate.

- The lawyers’ movement in Pakistan between 2007-2009 emerged in response to president Pervez Musharraf’s decision to dismiss the Chief Justice of Pakistan’s Supreme Court. Three years of civil resistance pushing for judicial independence forced Musharraf to reinstate the Chief Justice and led to Musharraf’s fall from power in 2008.

- Palestinians in the West Bank continue nonviolent resistance against Israel’s construction of a wall separating Palestinians from their land. Some villages, like Bil’in or Budrus, have become internationally recognizable symbols of this struggle against Israeli occupation.

- Iran’s Green movement in 2009 shook the foundations of government that had ruled the country for more than 30 years. The movement was unable to sustain mobilization in the face of violent repression. However, the next presidential elections in 2013 were not subject to falsification and a more moderate candidate won.

- In late-2010 and 2011, people’s mobilization started from Tunisia and spread to Egypt and other countries in the region. Unarmed people brought down seemingly irremovable and powerful autocratic leaders, but democratic consolidation after these transitions remains uneven. Some countries, such as Syria, saw their nonviolent movements overtaken by armed resistance with tragic consequences for the population.

- In 2014, people of Burkina Faso rose up, led by the popular campaign Balai Citoyen (“Citizen’s Broom”), and ended the rule of autocrat Blaise Compaoré in Burkina Faso, who had ruled the country for 27 years.

In more recent years, there have been nonviolent movements against corruption in countries such as Ukraine, Armenia, Moldova, Guatemala, Brazil, and Cambodia; struggles against authoritarian rule in Algeria, Sudan, Zimbabwe, Venezuela, Belarus, Russia, and Pakistan; nonviolent resistance against occupation in Palestine; for self-determination in West Papua, Western Sahara, and Tibet; for immigrant rights, minority rights, and police accountability and against climate change in the United States; for indigenous rights in Latin America; against violence and the drug war in Mexico; to preserve democracy in Hong Kong and Slovakia; and for women’s rights in India, the Middle East, China and North Africa.

What is the Record of Civil Resistance?

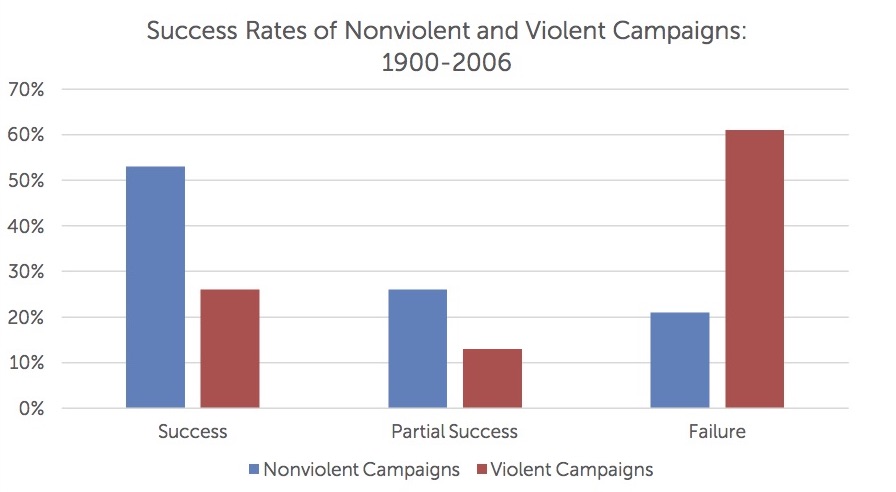

Not all civil resistance movements and campaigns succeed, but far more do succeed than is commonly assumed. What is their probability of success relative to other means of struggle?

These is no definitive measure of the success rate of civil resistance across all causes and circumstances. However recent award-winning research has compared the record of civil resistance movements and violent insurgencies that are confronting governments and seeking to achieve major objectives of either changing the government, seceding from a country, or ousting foreign occupiers. The results are clear:

Source: Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan, Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict, (New York: Columbia University Press), 2011

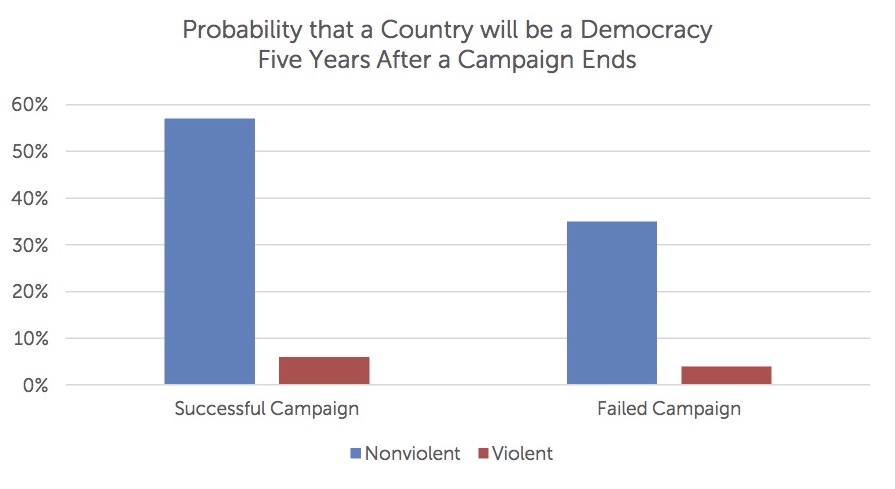

In addition, successful civil resistance struggles (and sometimes even unsuccessful civil resistance struggles) lead to dramatically more democratic outcomes than violent uprisings:

Source: Erica Chenoweth and Maria Stephan, Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict, (New York: Columbia University Press), 2011

What Factors Help Civil Resistance Movements Succeed?

Historically, and even to the present day, analysis of civil resistance movements has often presumed that these movements can only emerge and succeed under certain favorable key structural conditions. However, this assumption has been proven wrong repeatedly by actual events. Many movements have caught observers by surprise and occurred among underserved populations whose lack of economic power, shared history, and limited access to formal education and services led people to assume incorrectly that these populations could not mount effective resistance. At the same time, many civil resistance movements have also emerged and succeeded in highly repressive conditions where violence against activists and ordinary people was also assumed to preclude successful nonviolent resistance.

The available quantitative data needs to be expanded, but existing research supports these findings and points to the fact that even highly challenging conditions do not categorically prevent successful civil resistance. While daunting conditions are often present, a movement’s skills and strategic choices are also important, and successful movements apply their skills and strategic choices to create and take advantage of situational opportunities, and to overcome and transform challenging social and economic conditions.

This is the basis for the work of the International Center on Nonviolent Conflict, that by studying and sharing information and educational resources about how movements work and engage in effective resistance around the world for diverse causes, the skills and strategic choices of resisters can enable them to be more effective in winning their rights. You can read more about our theory of change and impact.